Timeline: Fr. John Enright and San Miguelito Mission

May 1, 1953 – Enright ordained a priest by Samuel Cardinal Stritch

July 1953 – Enright named associate pastor of St. Andrew’s Parish, Chicago

July 1956 – Enright named associate pastor of St. Henry Parish, Chicago

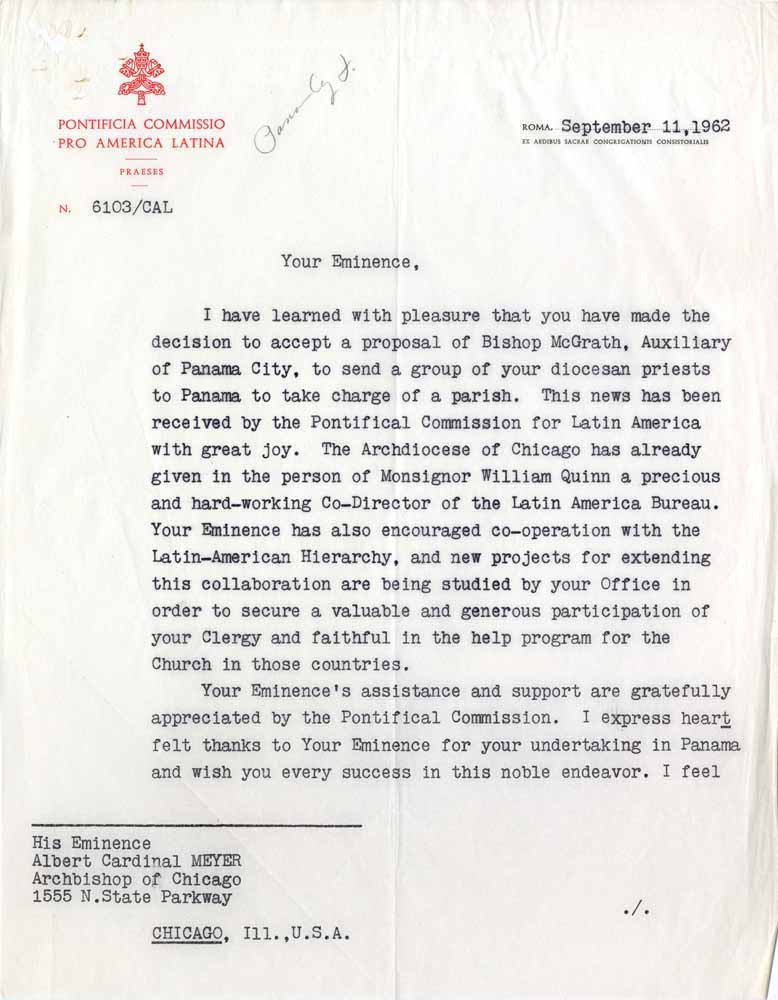

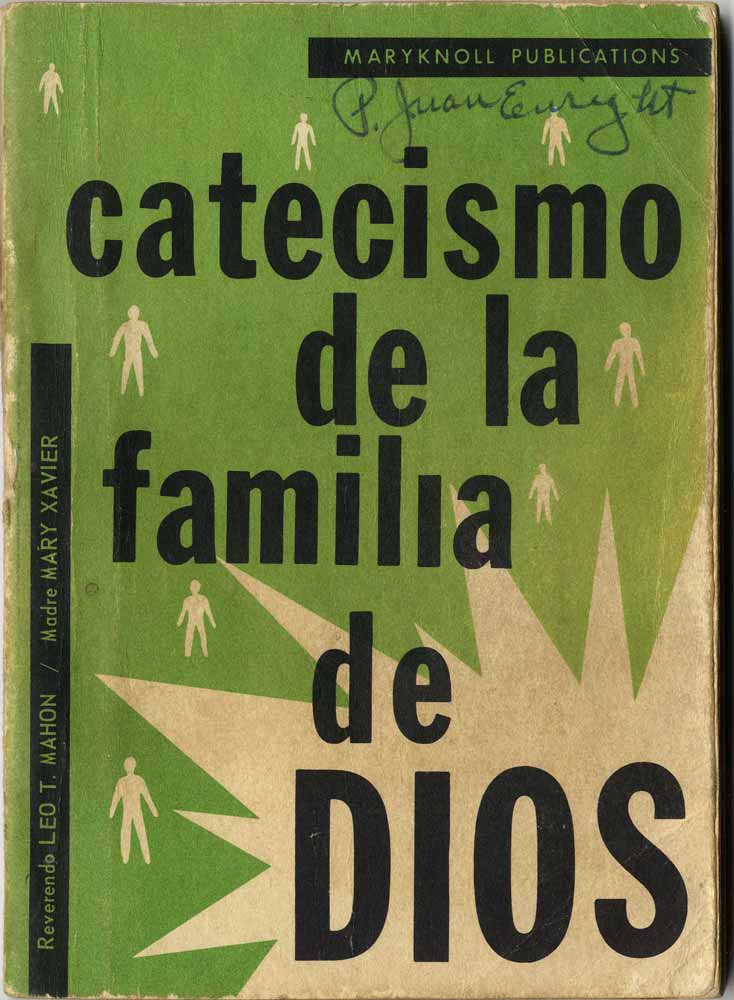

February 15, 1962 – Rev. Gilbert Carroll and Rev. Leo Mahon submit a proposal to Cardinal Meyer suggesting a Chicago mission in either Puerto Rico or Panama

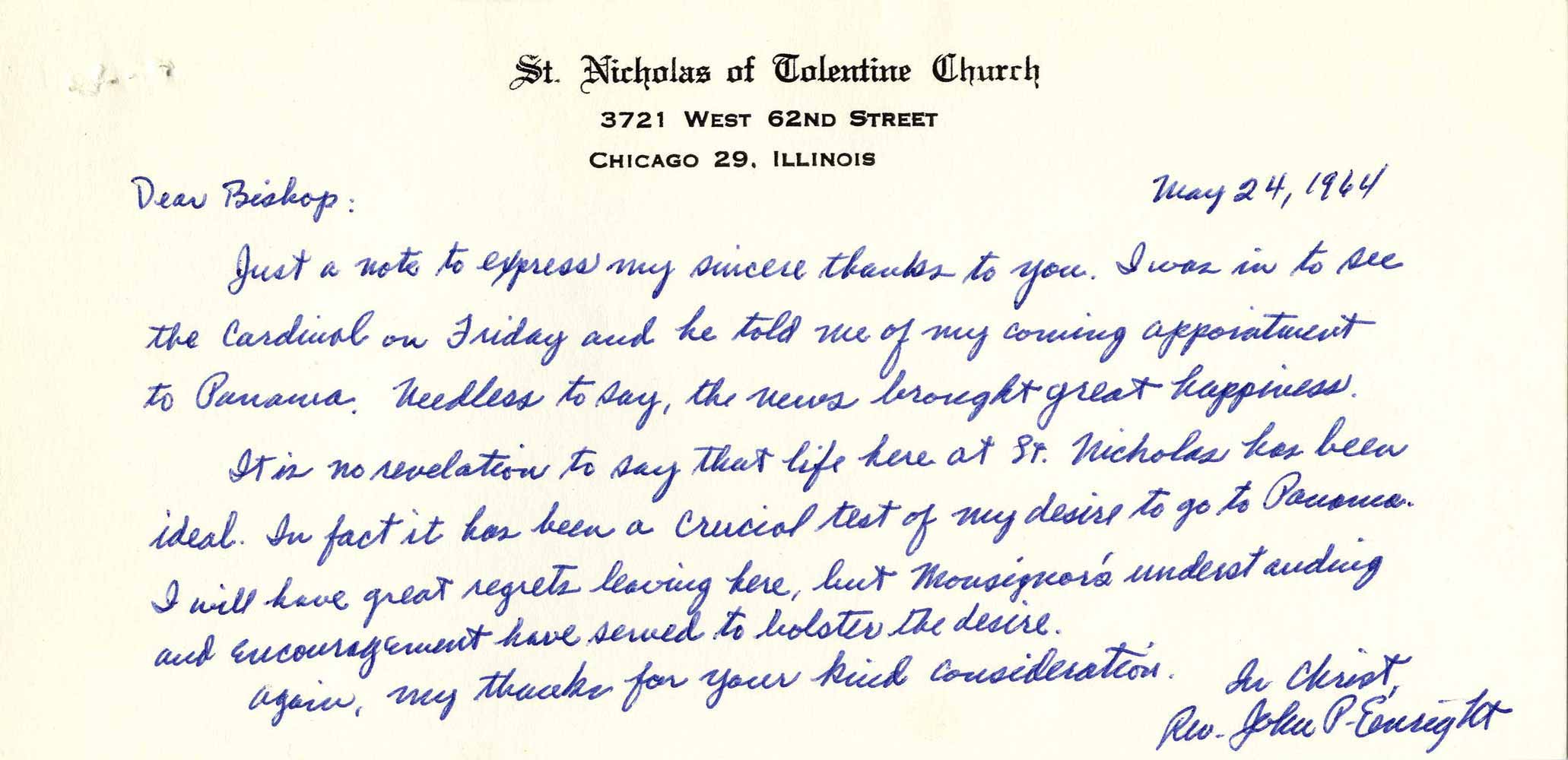

July 1962 – Enright named associate pastor of St. Nicholas of Tolentine, Chicago

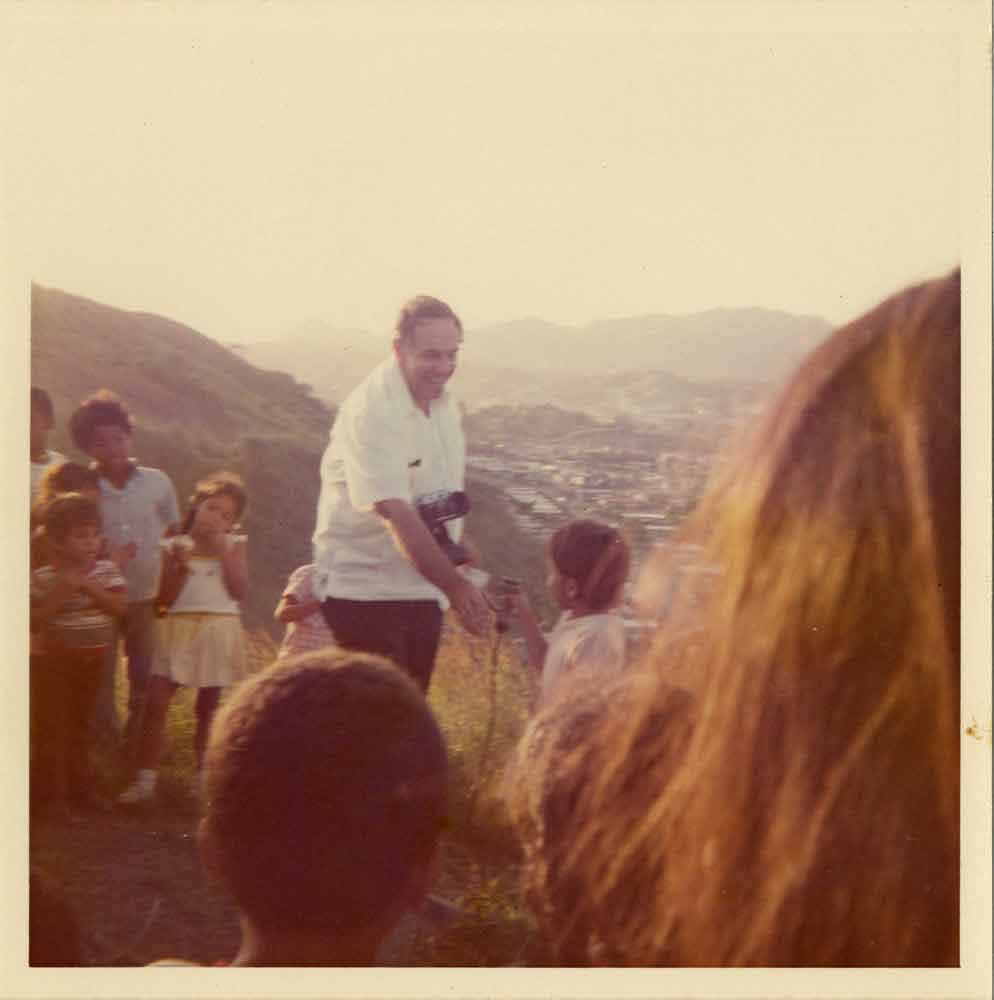

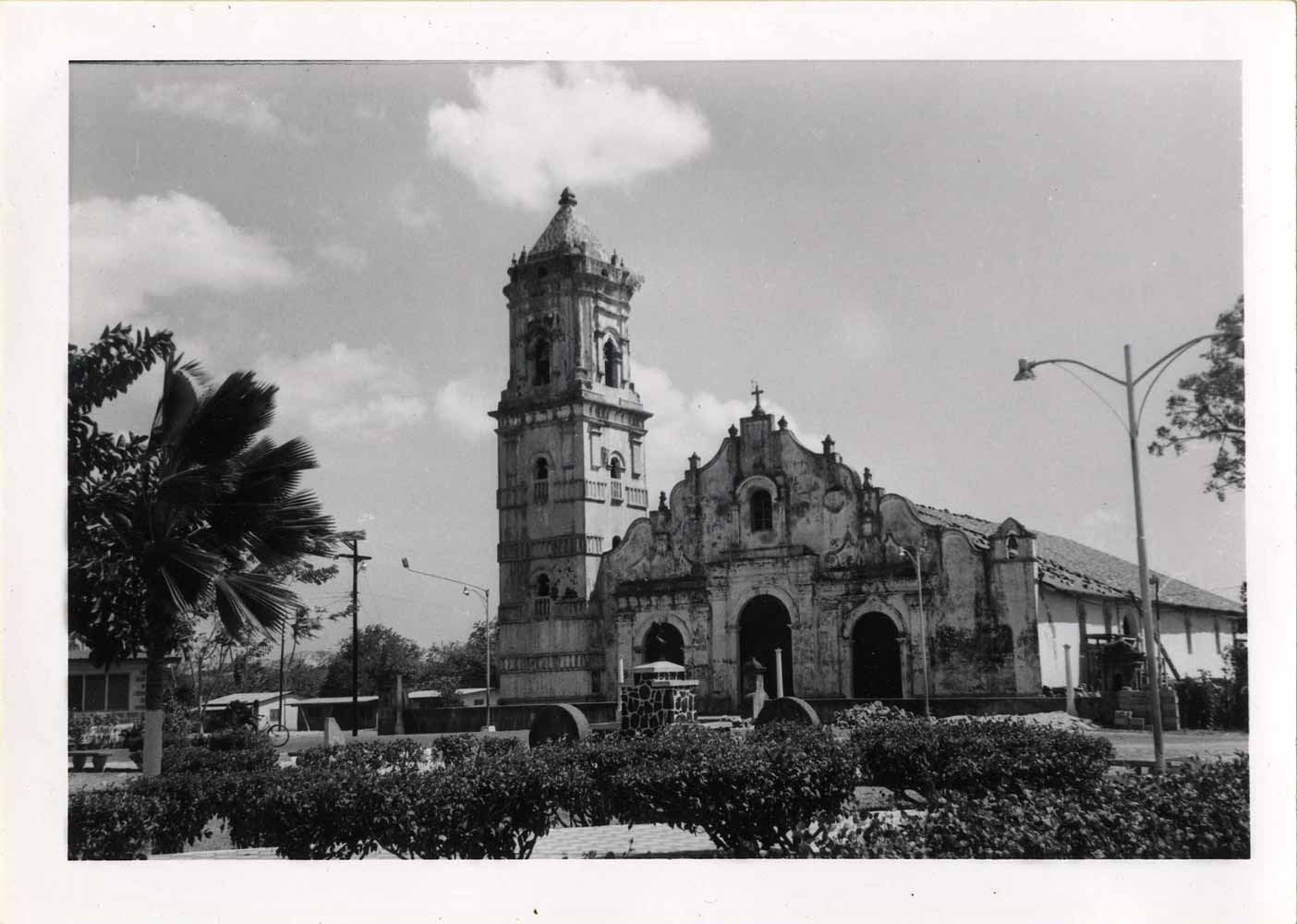

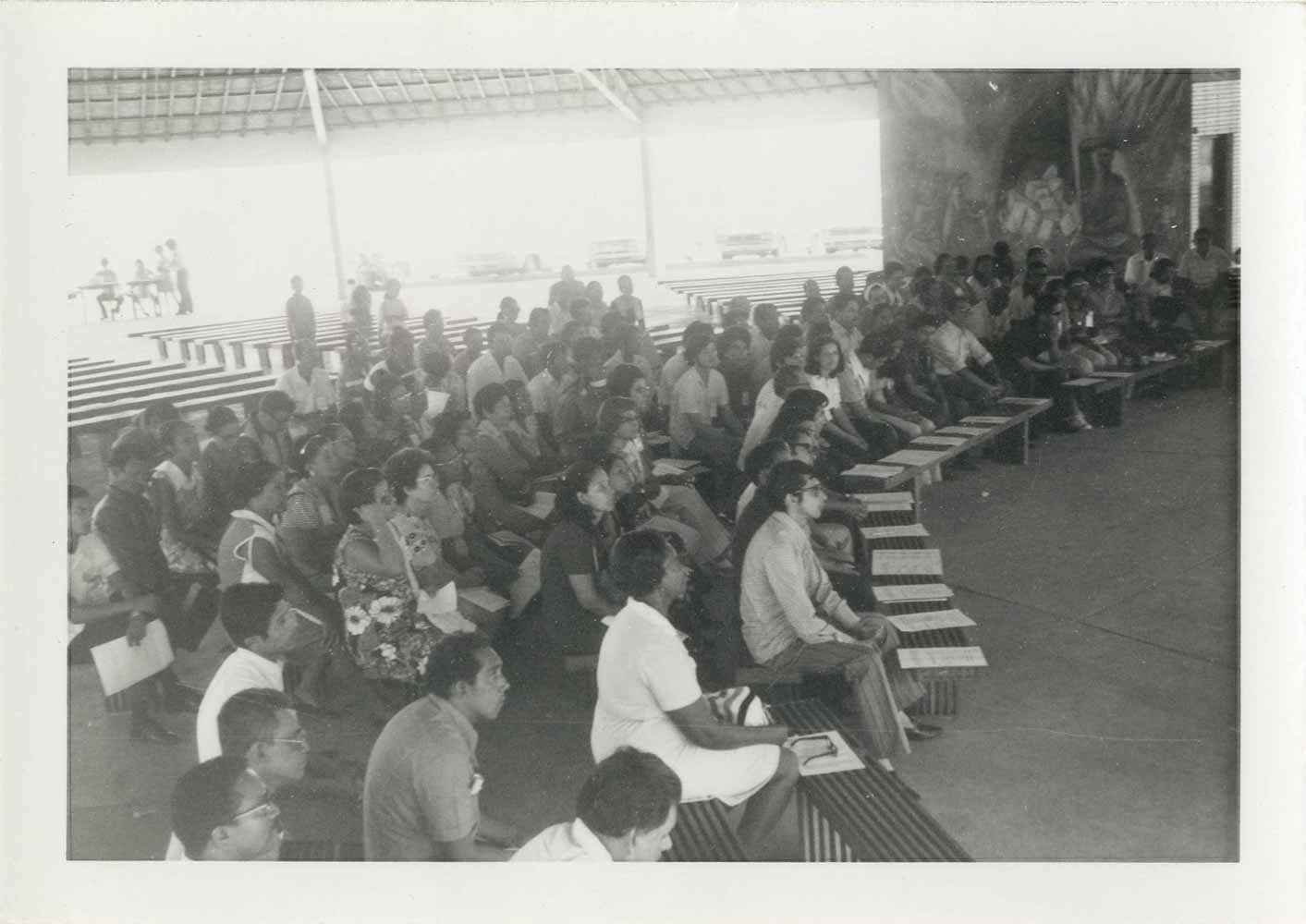

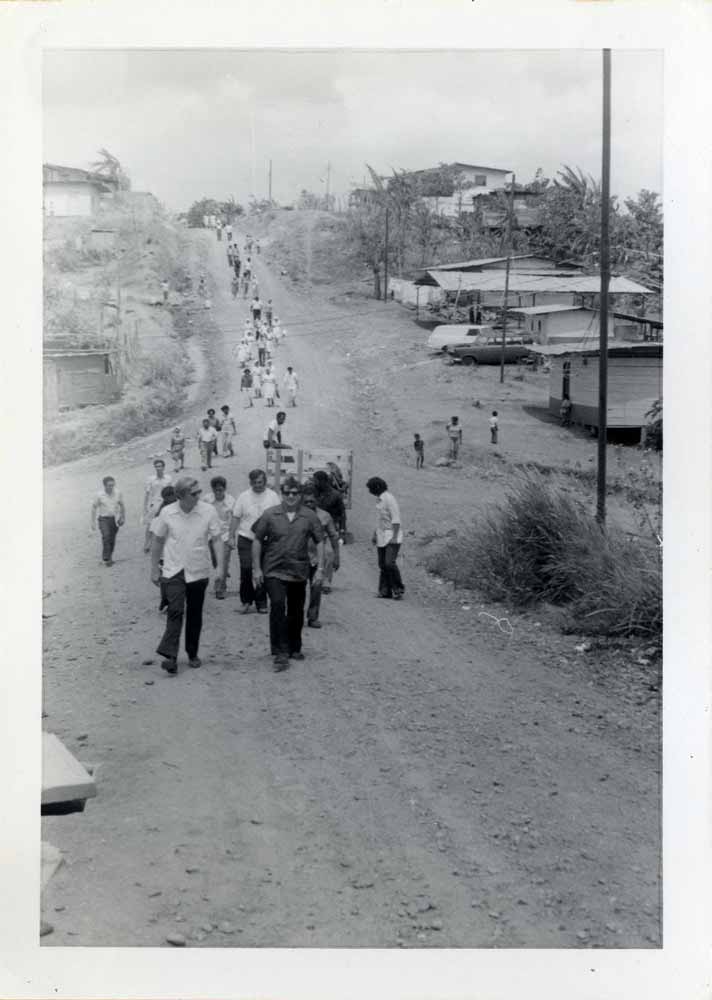

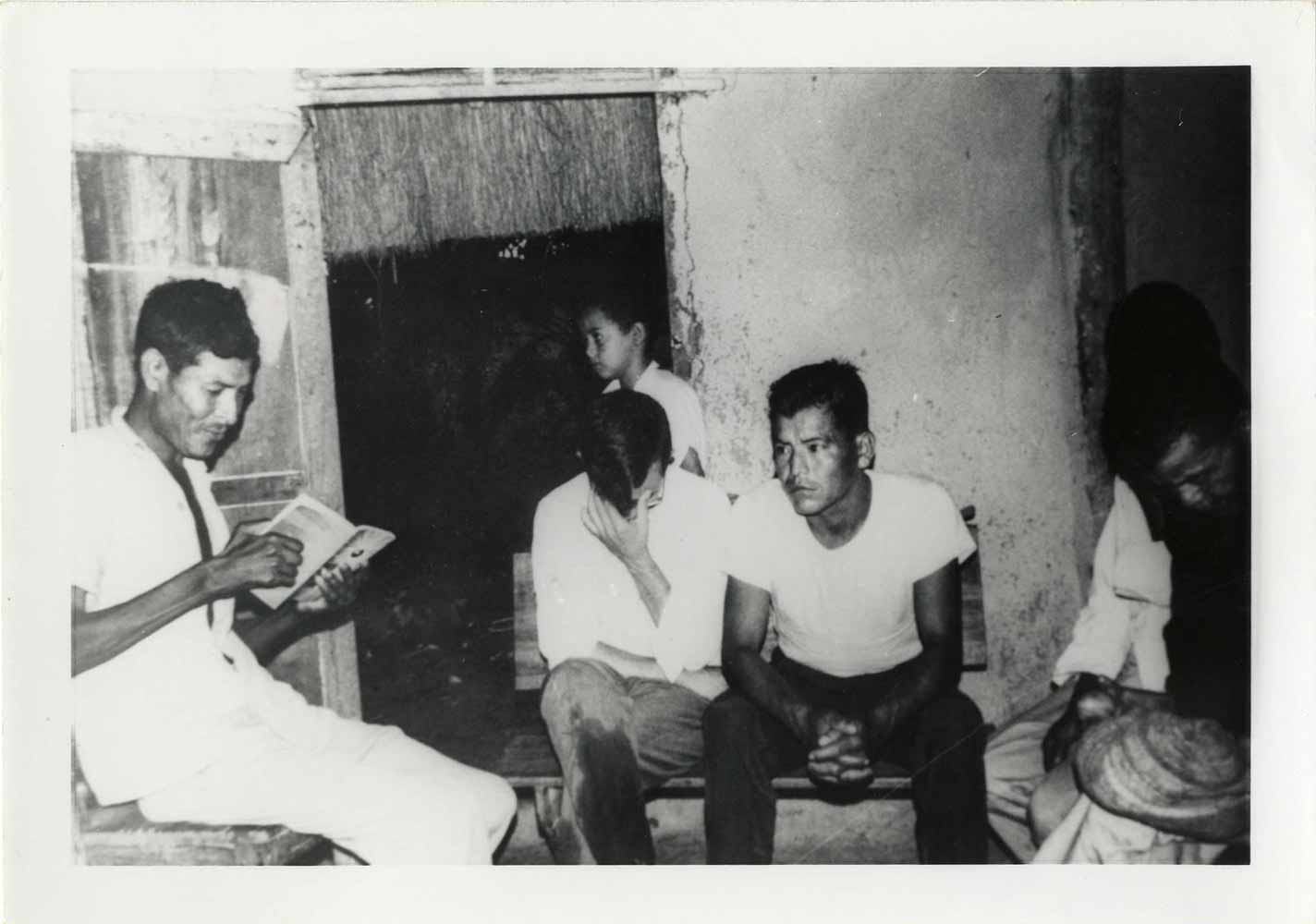

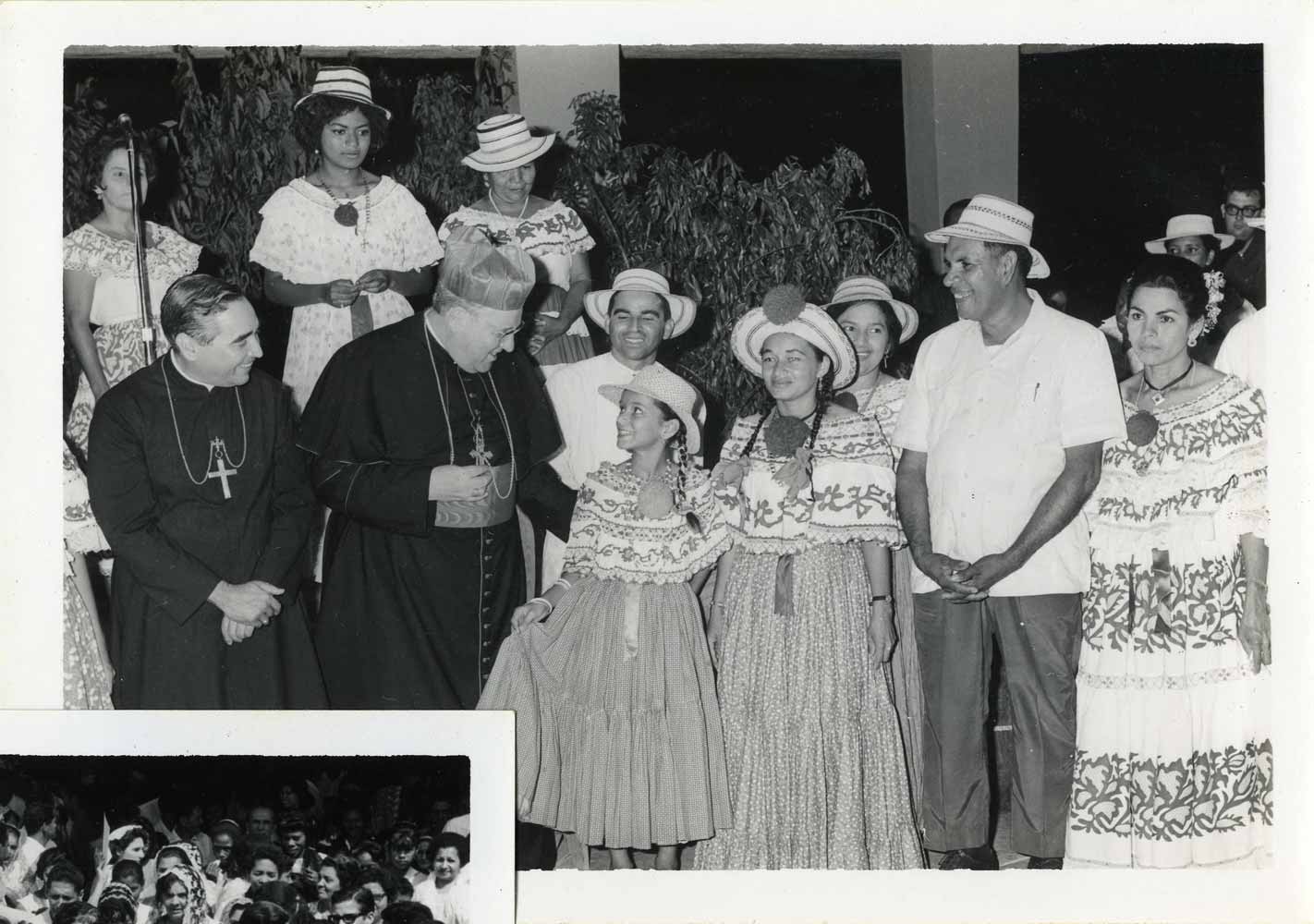

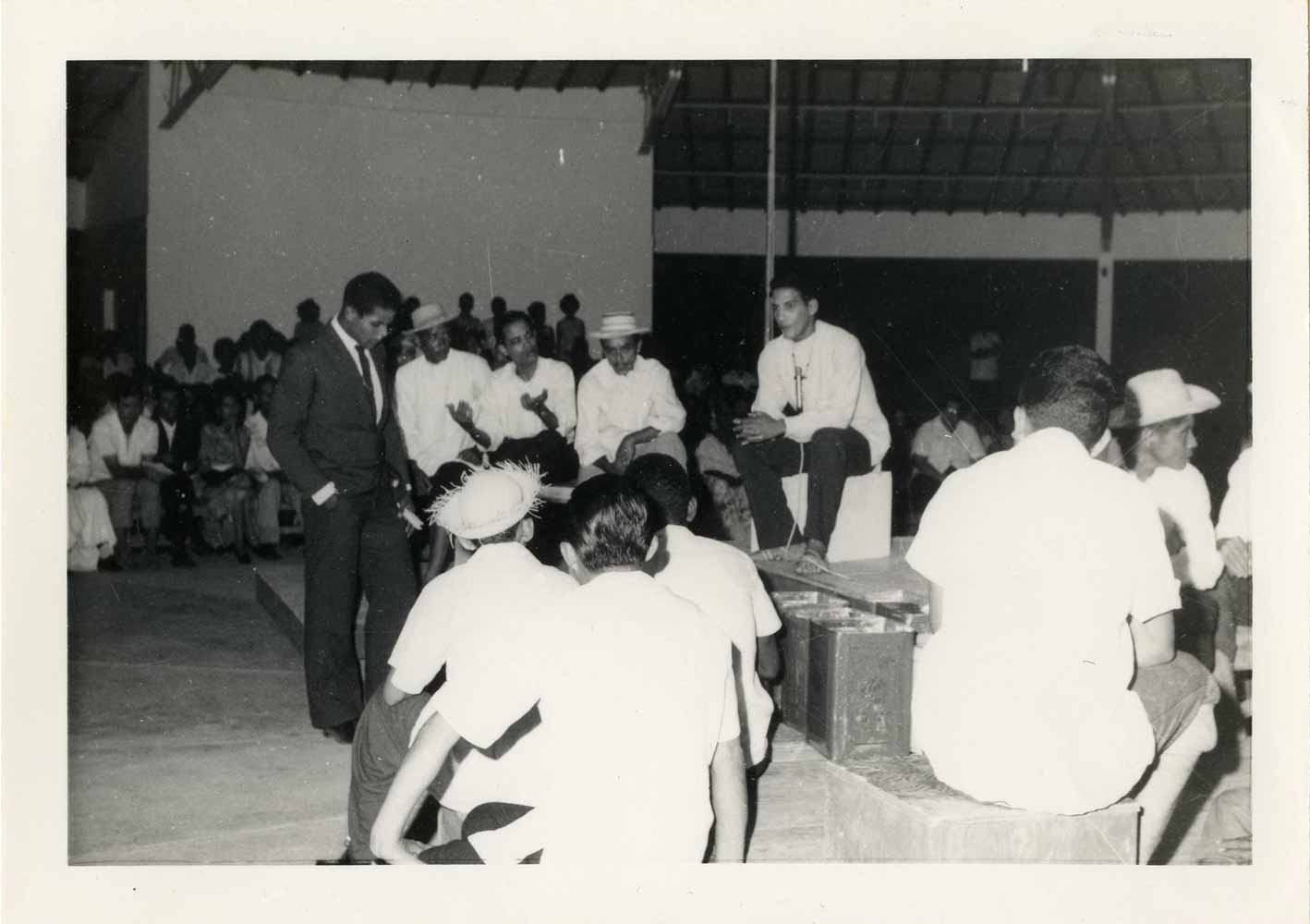

Spring 1963 – Fr. Leo Mahon, Fr. Jack Greeley, and Fr. Bob McGlinn arrive in San Miguelito and begin the mission

May 1964 – Cardinal Meyer appoints Enright to Panama

Until December 1964 – Enright sent to Cuernavaca, Mexico (Center of Intercultural Formation) to learn Spanish

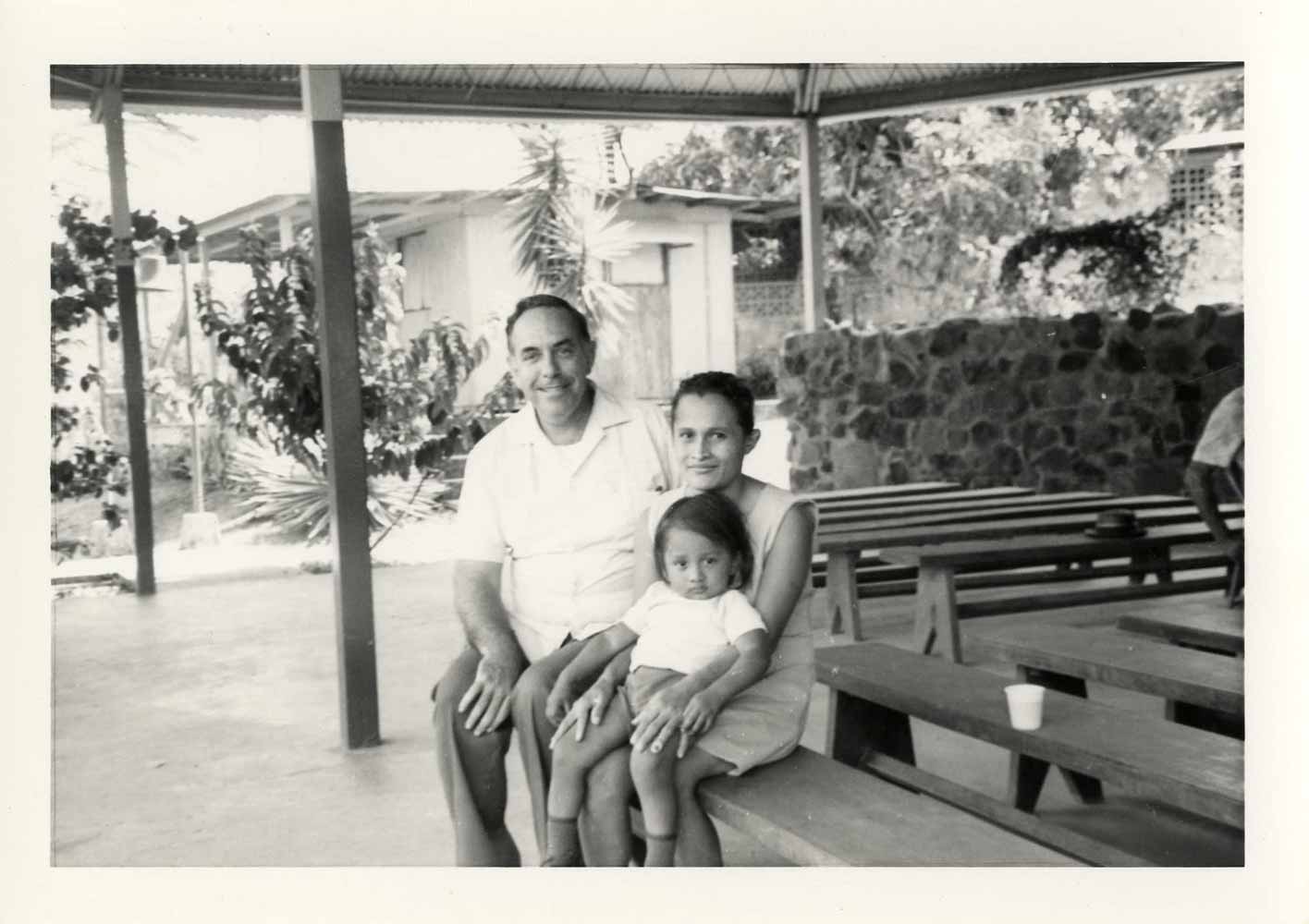

Christmas 1964 – Enright arrives in San Miguelito just prior to Christmas, and celebrates three masses on Christmas Eve

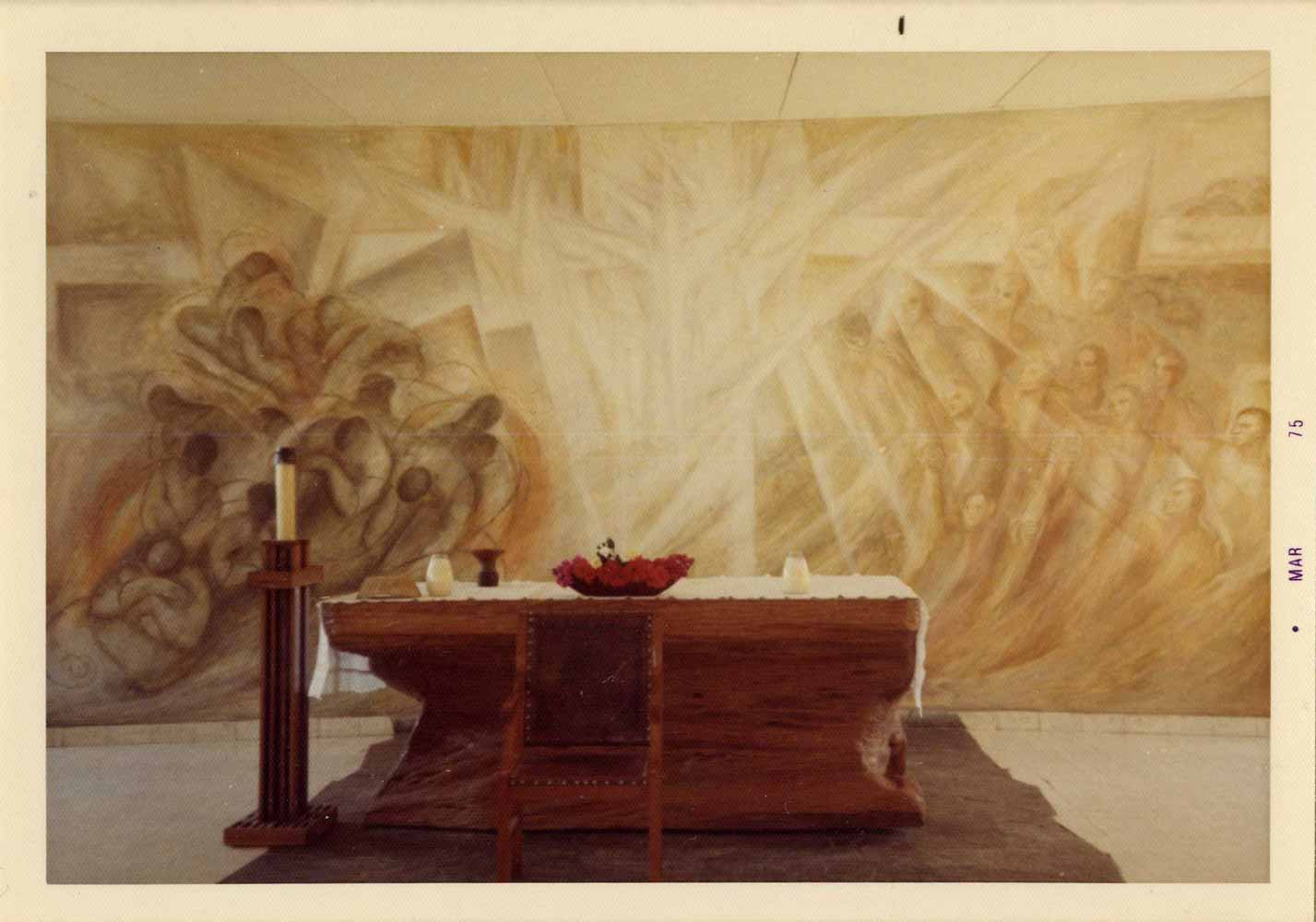

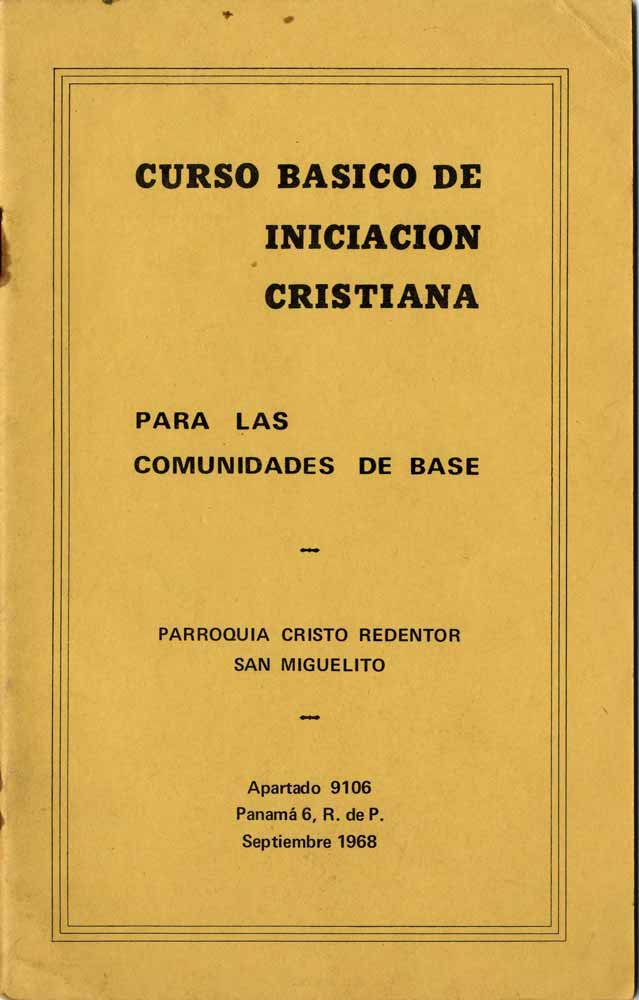

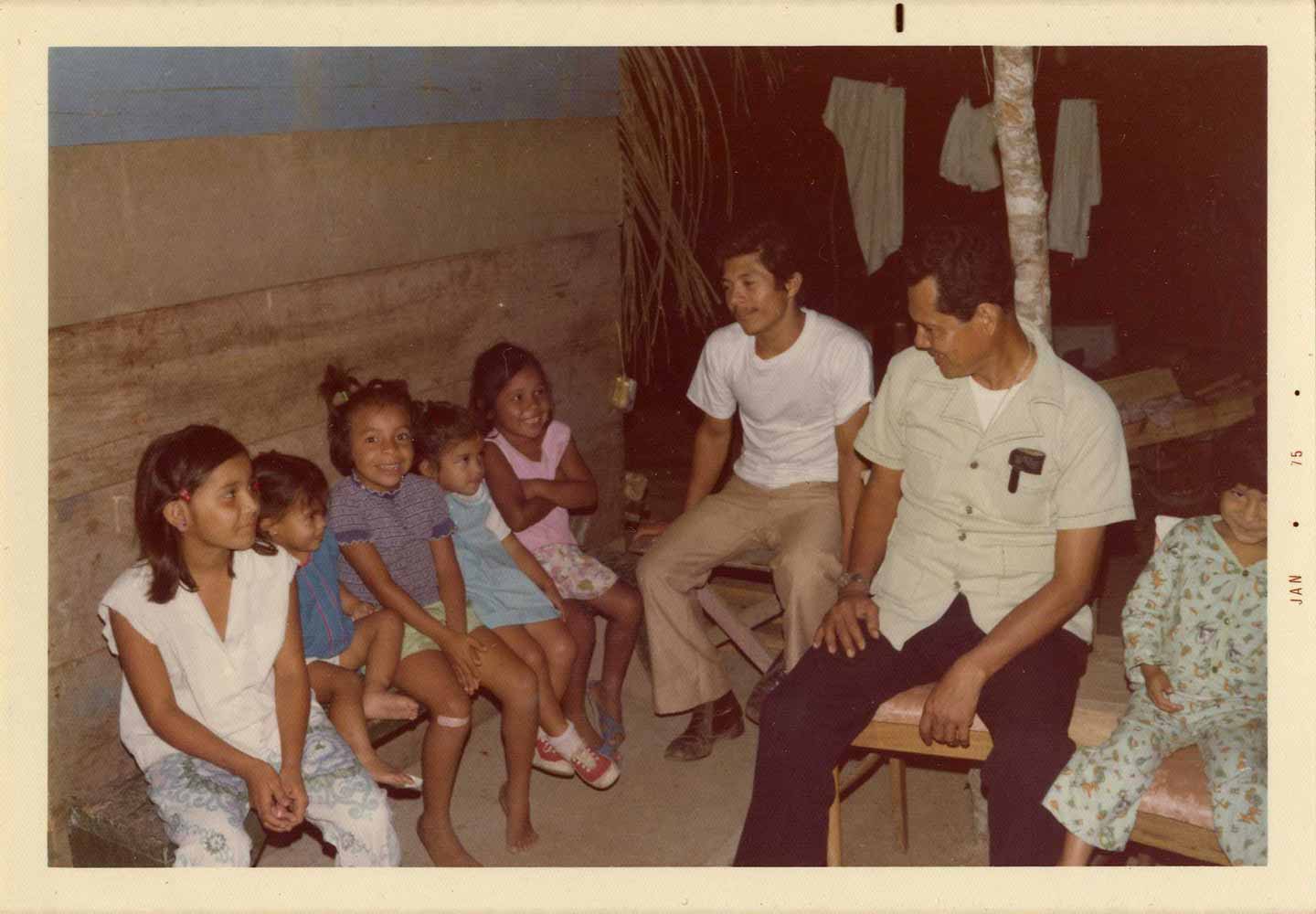

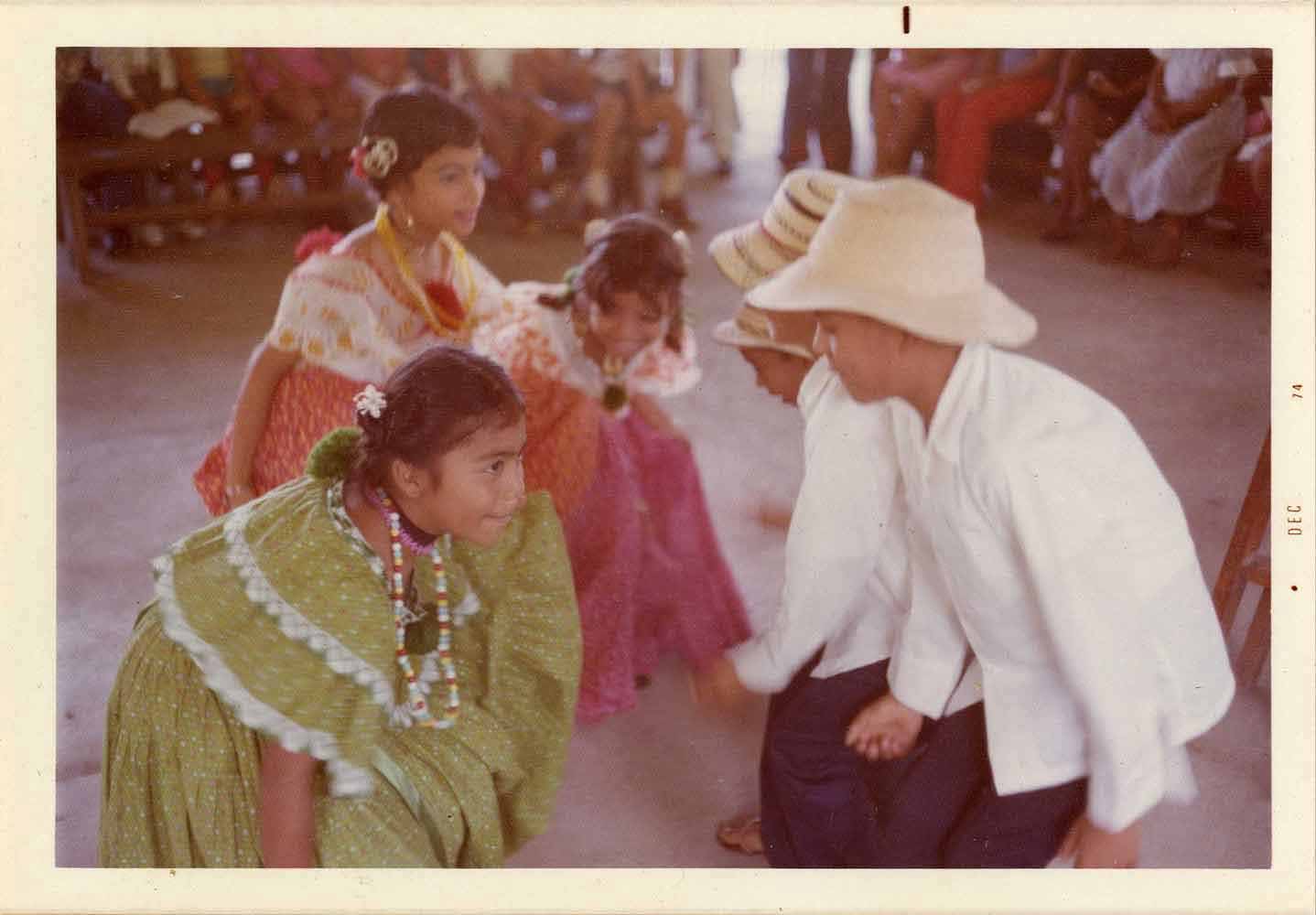

1965/1966 – Enright named assistant pastor under Greeley at Cristo Redentor

April 1966 – Local parishes founded and Enright made pastor at La Sagrada Familia in San Isidro (10,000 people)

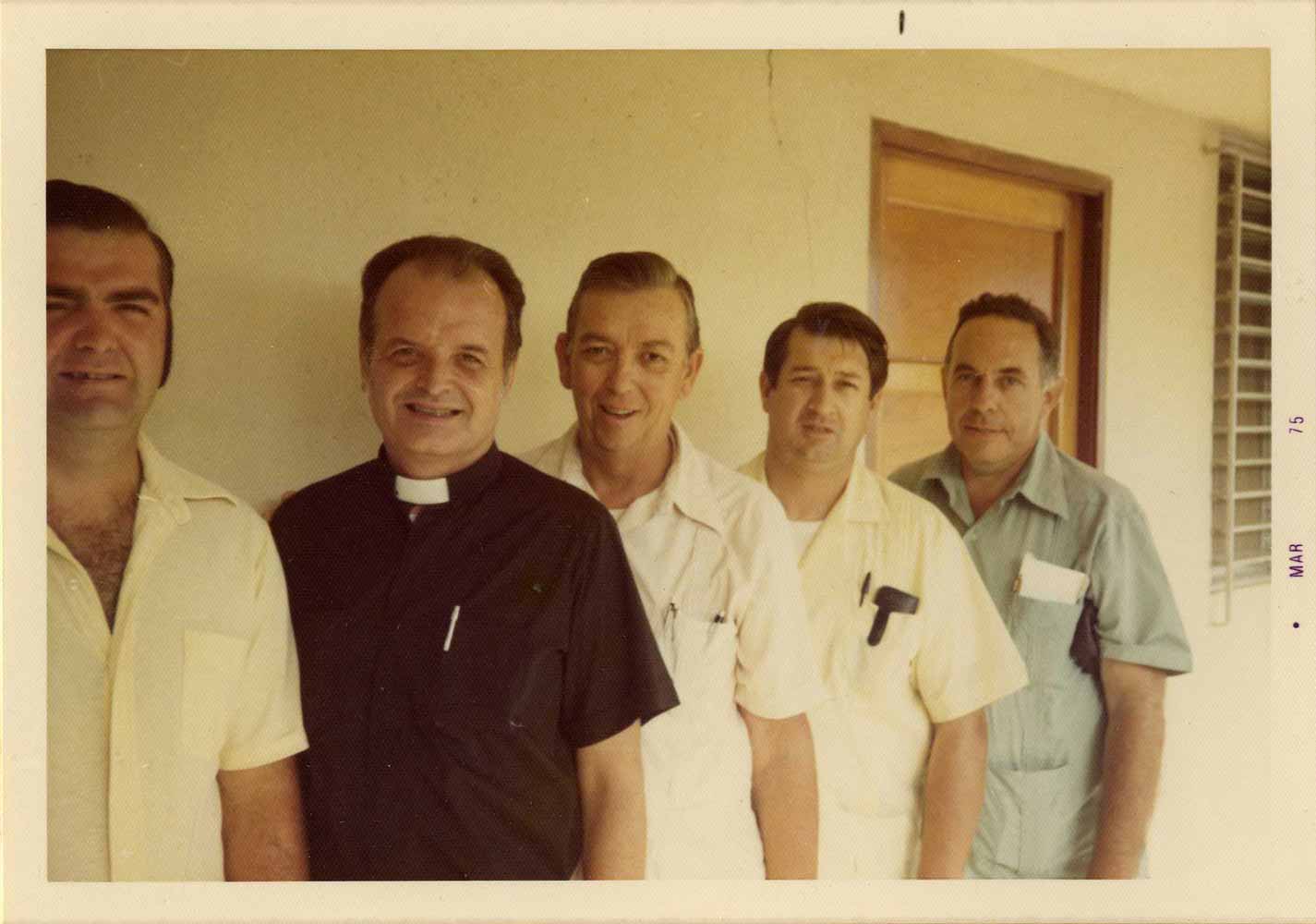

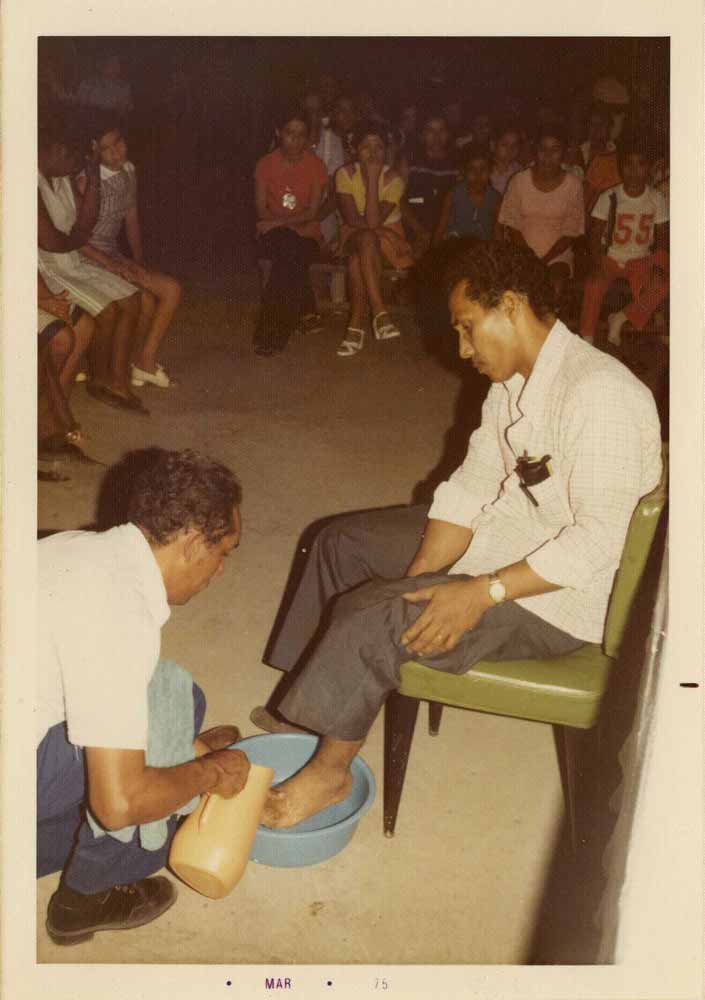

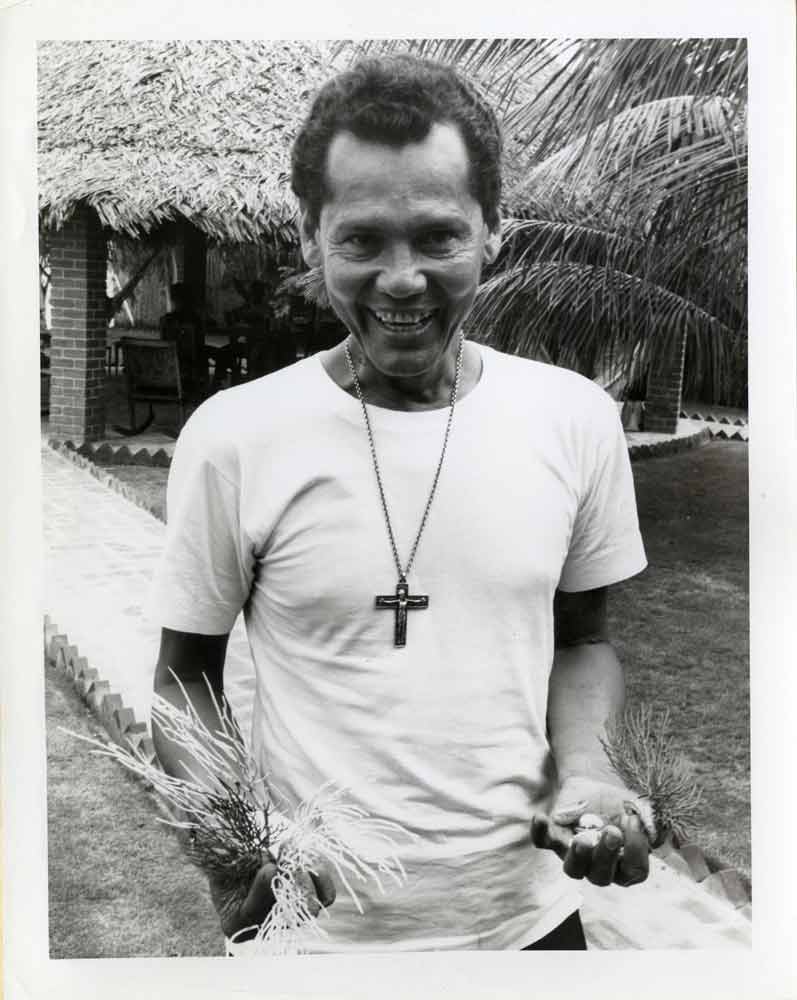

1975 – Fr. Leo Mahon leaves Panama; Enright becomes the senior member of the San Miguelito team

1976 – Enright leaves Panama and begins work as pastor at Epiphany Parish, 2524 South Keeler Avenue

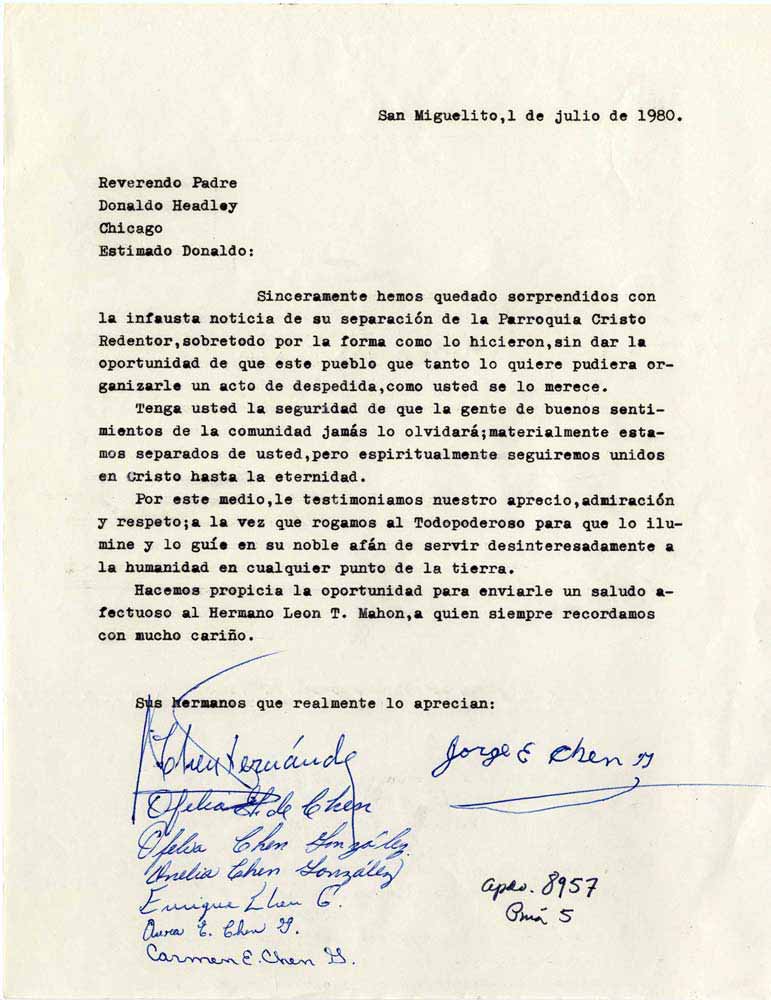

1980 – Fr. Donald Headley, the last Chicago priest at San Miguelito, is prevented from returning to Panama, and the presence of Chicago priests at San Miguelito is ended

January 1993 – Enright named Vicar of Santa Tersita, Palantine

1994 – Enright retires from Epiphany

July 1997 – Enright retries to Mayslake Village, Diocese of Joliet

October 1998 – Enright becomes an associate to the Hispanic Ministry Program, Joliet

2001-2002 – Enright visits the Joliet Mission Program in Sucre, Bolivia