Table of Contents

New Leadership and a New Mission

Faith Formation and the Mission Field

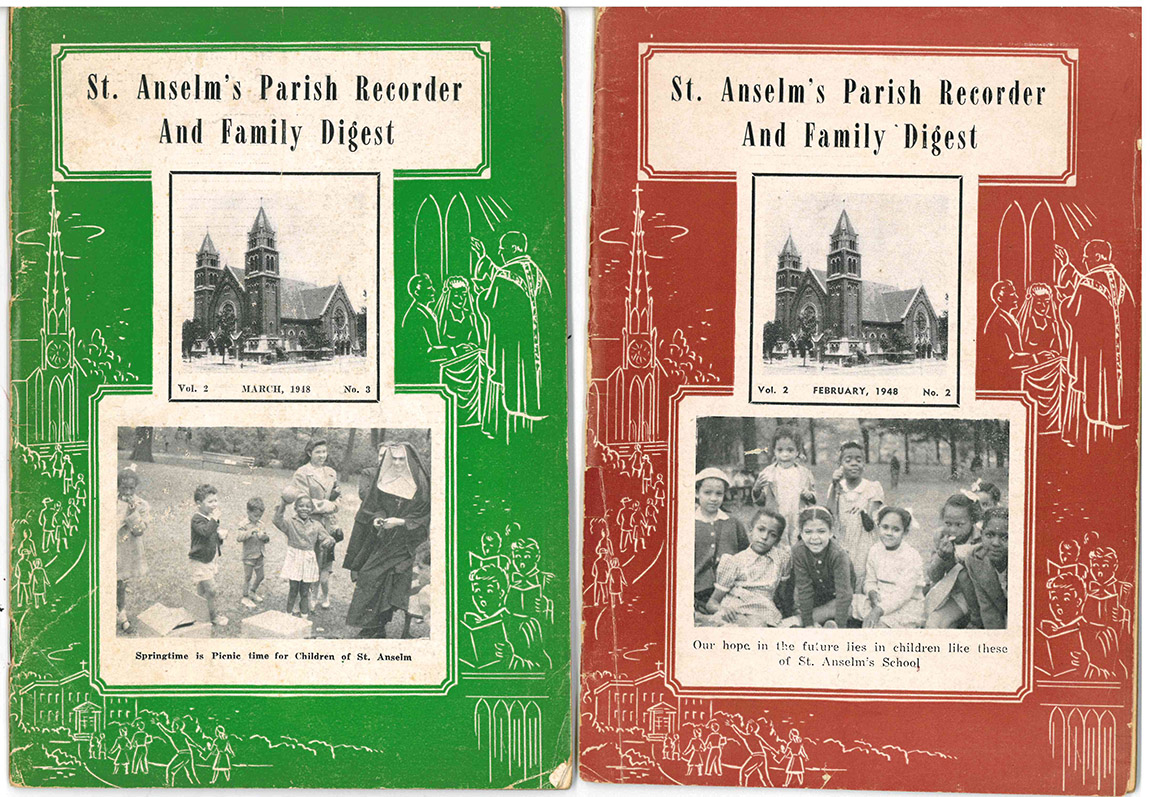

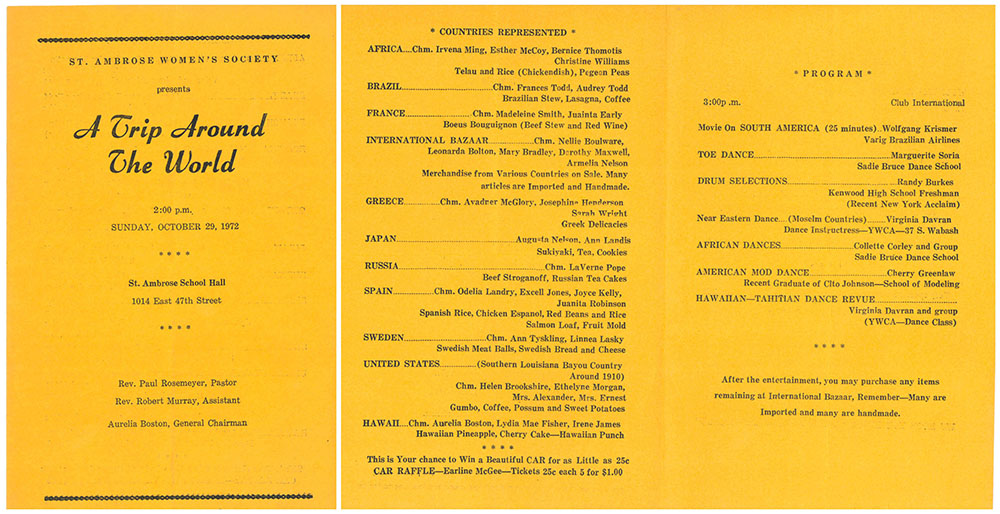

Fun and Fellowship at the Parish

Schools: Promise and Opportunity

Change Once More… Our Lady of Africa

Click on images to see them at a larger resolution.

Table of Contents

New Leadership and a New Mission

Faith Formation and the Mission Field

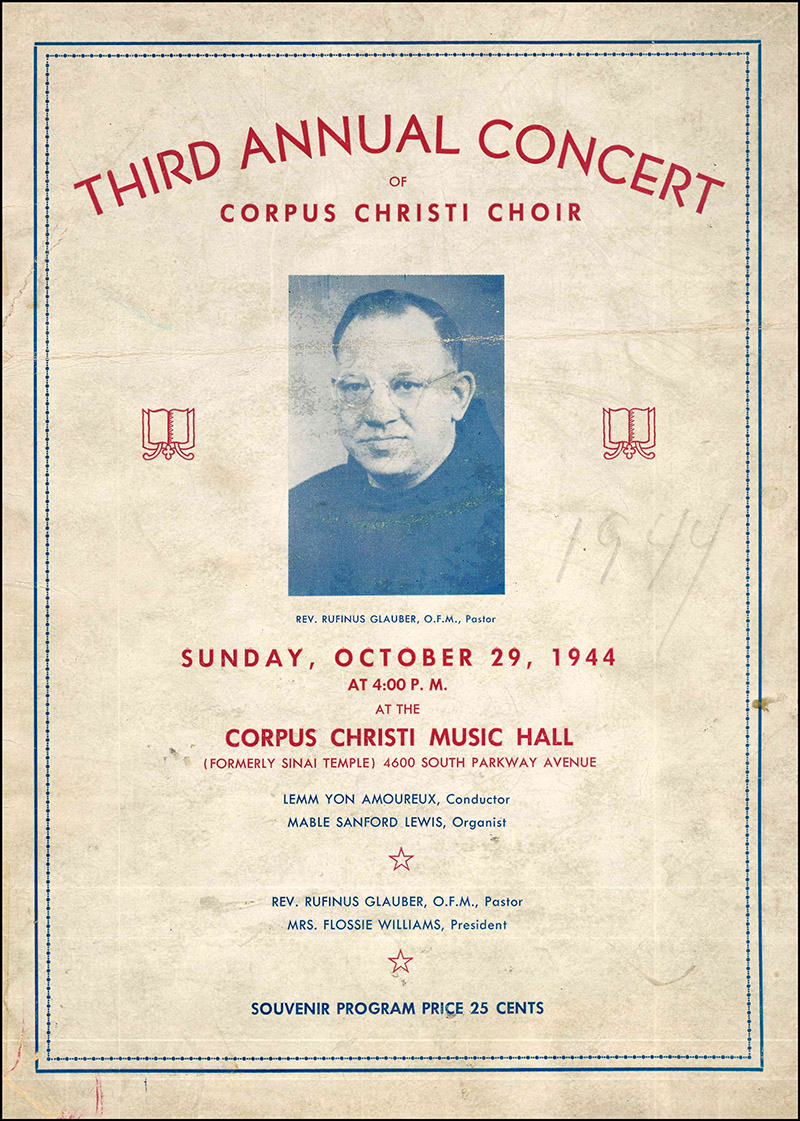

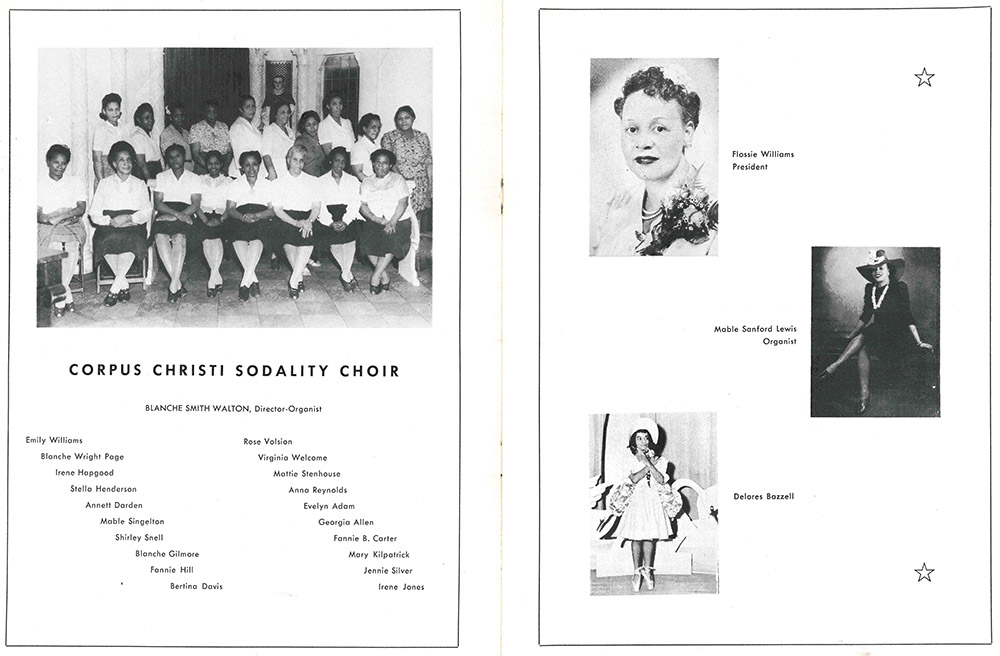

Fun and Fellowship at the Parish

Schools: Promise and Opportunity

Change Once More… Our Lady of Africa

Click on images to see them at a larger resolution.

The material featured in this exhibit comes from the historical collections of St. Ambrose, St. Anselm, St. Elizabeth, and Corpus Christi, and Holy Angels, which united to form the parish Our Lady of Africa in the summer of 2021. These parishes and the Black communities of Bronzeville Washington Park, and Kenwood have a rich tradition and history dating back to the 19th century. The Archives and Records Center houses the historical records of many such parishes across the Archdiocese.

Back to top1889/1890 saw the arrival of Fr. Augustus Tolton in Chicago. Tolton was a former slave, fluent in multiple languages, and the first Black priest in the United States. Fr. Tolton would say mass for the small group of Black Catholics in the basement of Old St. Mary’s. At that time, there were 50 Black Catholic families scattered around the city of Chicago. As their numbers grew so did their desire for a church of their own. Fr. Daniel Riordan, the founder of St. Elizabeth, marshalled his considerable oratorical and money-raising talents to Tolton’s cause and helped secure partial funding for the church that would become St. Monica, the first Black parish in the city of Chicago. Much beloved in the neighborhood, Fr. Tolton had hoped the church would be a beacon for Black converts. Unfortunately, he would not see that dream become a reality: Tolton suddenly died of heat stroke in 1897 before the church was finished. Fr. Riordan became the dual pastor of St. Monica and St. Elizabeth after Tolton’s death.

Fr. Tolton, who celebrated mass in an unfinished church to a small congregation, had felt that success eluded him, but in hindsight people recognized the important work he did in gathering the city’s Black Catholics and building their community. He may not have lived to see it, but the South Side was quickly changing and would soon become a fertile field for conversion. By the 1910s there were 400 Black Catholic families, and that number was growing. Over the next few decades, the Great Migration brought hundreds of thousands of Black families from the south into the north, particularly into cities like Chicago and Detroit. They came looking to escape vicious Jim Crow laws and to find more prosperity in the booming metropoles of the industrial North. Many cited a better future and education for their children as the primary motivating factor in their move.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the South Side of Chicago—and Bronzeville/Washington Park/Kenwood region in particular—was predominantly the home of well-to-do Irish Americans. This ethnic homogeneity is reflected in the surnames of the founding pastors of the Our Lady of Africa parishes: Foley, Gilmartin, Riordan, Henneberry, Tighe. As their congregations outgrew old wooden frame churches, these men raised money to build magnificent churches for their flocks.

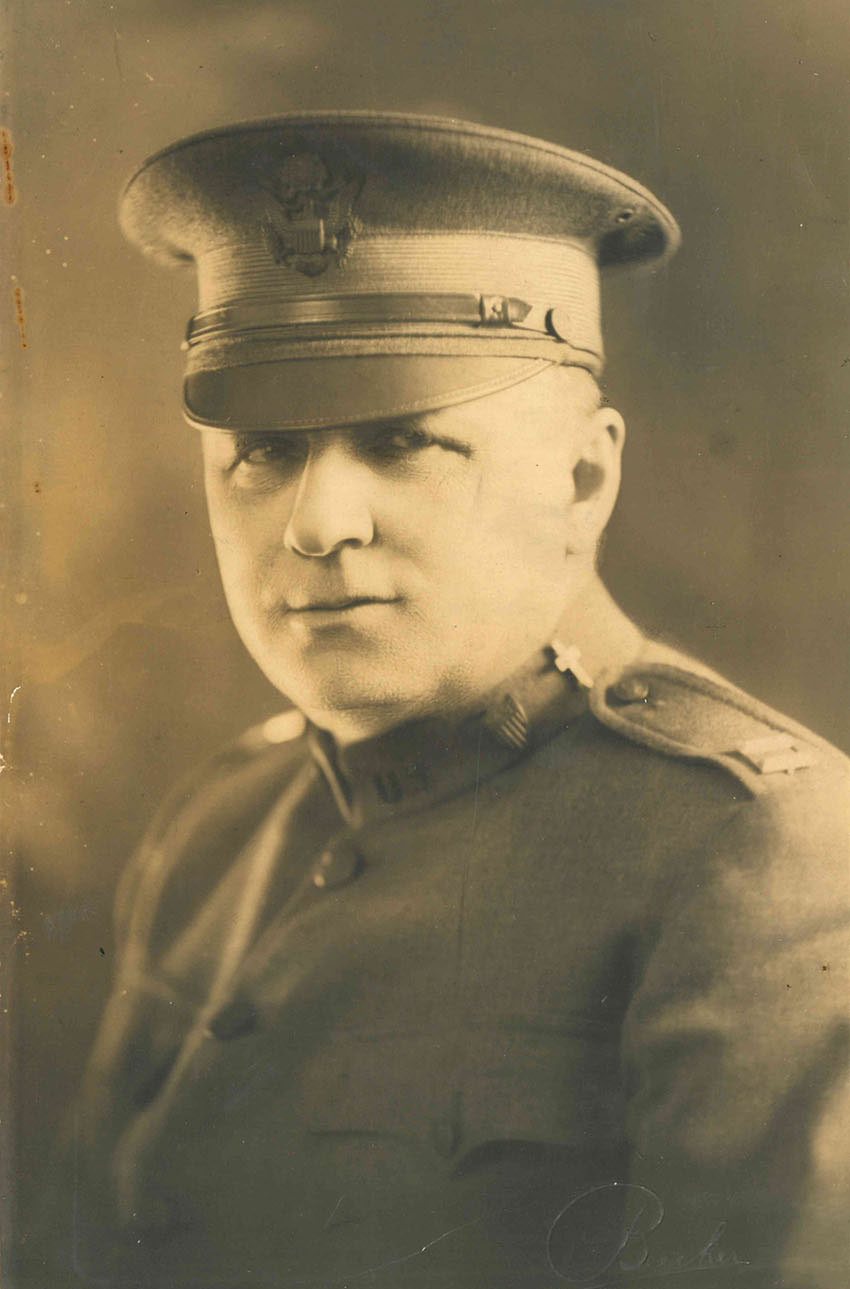

The prosperity of the South Side is mirrored in their resplendent churches. St. Elizabeth and Holy Angels were the first to be built in 1892 and 1896 respectively. Corpus Christi’s second pastor, Fr. Thomas O’Gara, oversaw the building a large stone campus in an impressive Italian Renaissance style in 1916. Msgr. William Foley (pictured here), a World War I chaplain and first pastor of St. Ambrose, raised money to build an impressive Gothic church on 47th St. in 1926. St. Anselm’s imposing structure was dedicated one year earlier.

The prosperity of the South Side is mirrored in their resplendent churches. St. Elizabeth and Holy Angels were the first to be built in 1892 and 1896 respectively. Corpus Christi’s second pastor, Fr. Thomas O’Gara, oversaw the building a large stone campus in an impressive Italian Renaissance style in 1916. Msgr. William Foley (pictured here), a World War I chaplain and first pastor of St. Ambrose, raised money to build an impressive Gothic church on 47th St. in 1926. St. Anselm’s imposing structure was dedicated one year earlier.

However, even as these churches were being built, Black migration, racial conflict, and white flight resulted in these newly built churches losing their early parishioners, with dwindling mass attendance and money to maintain these huge structures.

Fr. Joseph Eckert, SVD. Date unknown (possibly 1930s)

After the death of Fr. Tolton, the Archdiocese did not have a solid plan for what to do with the Black community that was rapidly expanding at St. Monica. In a 1917 letter to the provincial of the Society of the Divine Word, Fr. J.A. Burgmer, Mundelein granted the Techny Fathers control of St. Monica and authority to begin an apostolate to the African American community in Bronzeville. St. Monica would be designated the “ethnic” parish for Black Catholics in the city, as there were Irish, German, and Polish churches. In a controversial move, Mundelein forbade white Catholics from attending St. Monica, although he allowed Black Catholics to attend church elsewhere if convenient. Cardinal Mundelein believed that this measure would strengthen and unify the Black community, but it caused Black parishioners to protest, as they believed that they were being “segregated” into a single church. The first SVD pastor, Fr. Augustine Reissman, felt the brunt of the community’s anger and left in 1921, feeling singled out and left to dry.

That year, the SVDs chose Fr. Joseph Eckert, SVD to replace him. Eckert, born in Germany in 1884 and at that time a professor at the Divine Word seminary, was loath to leave his beloved teaching post. But he acquiesced, remembering what inspired his vocation was a desire to save souls. With zeal, he quickly endeared himself, often personally visiting every new parishioner at their homes, introducing himself to non-Catholics, and enmeshing himself in the community. His singular rule was to “be kind and charitable to all.”

“…Within a few weeks I became accustomed to the ordinary routine of parish life and I began to like it, especially in view of the fact that the Colored Catholics responded well and seemed to take an active interest in parish affairs. I also came to realize what a gigantic task lay before me—a task greater than either my superiors or I ever dreamed of… I became fully aware that there was a real soul-saving and pioneer missionary work before me and not merely a reclamation of lost sheep, but that I had the best opportunities to give my missionary vocation a real and severe test. I made up my mind to go out and get converts…”

-Fr. Joseph Eckert, undated

In 1924, Mundelein merged St. Monica with St. Elizabeth, which had been steadily declining. By the time St. Elizabeth burned down in 1930, the congregation was too large for a single parish. Rather than build a larger church, Mundelein pragmatically looked to the equally struggling St. Anselm. In 1932, over the protests of the remaining whites, Mundelein gave St. Anselm's to the SVDs with Fr. Eckert as its new pastor. He instructed Eckert: “Take good care of all the people in the parish, irrespective of race or color, and make as many converts as possible… Fill St. Anselm’s church.” Eckert recounted how the white parishioners were shocked to learn that Eckert was white. They assumed that the priest making waves at St. Elizabeth could only have been Black. From then on, the Divine Word fathers would be a fixture of the neighborhood.

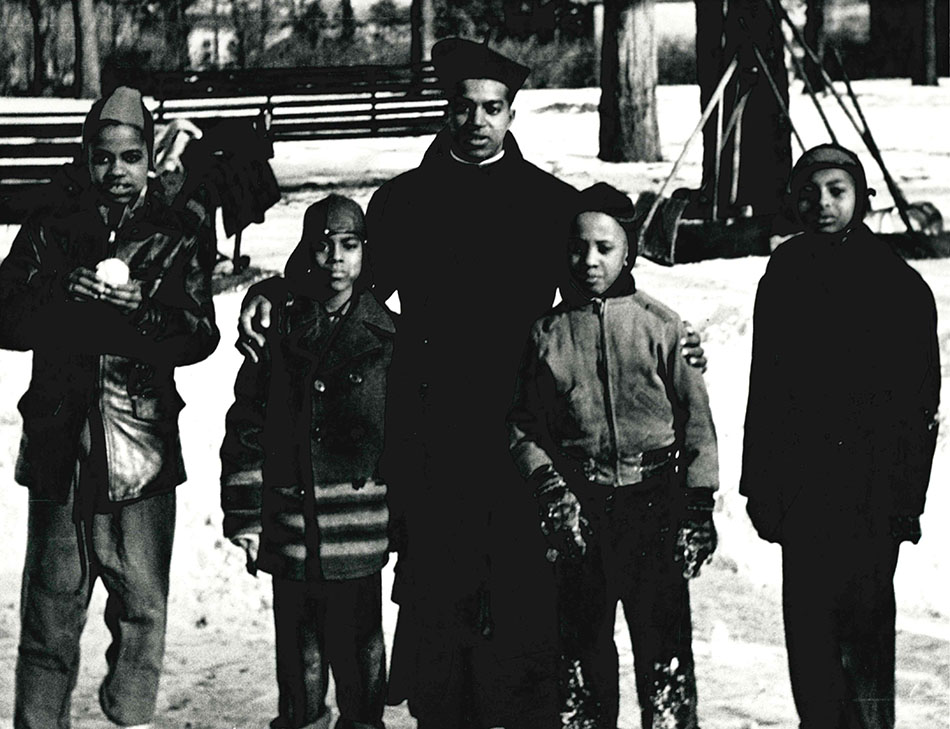

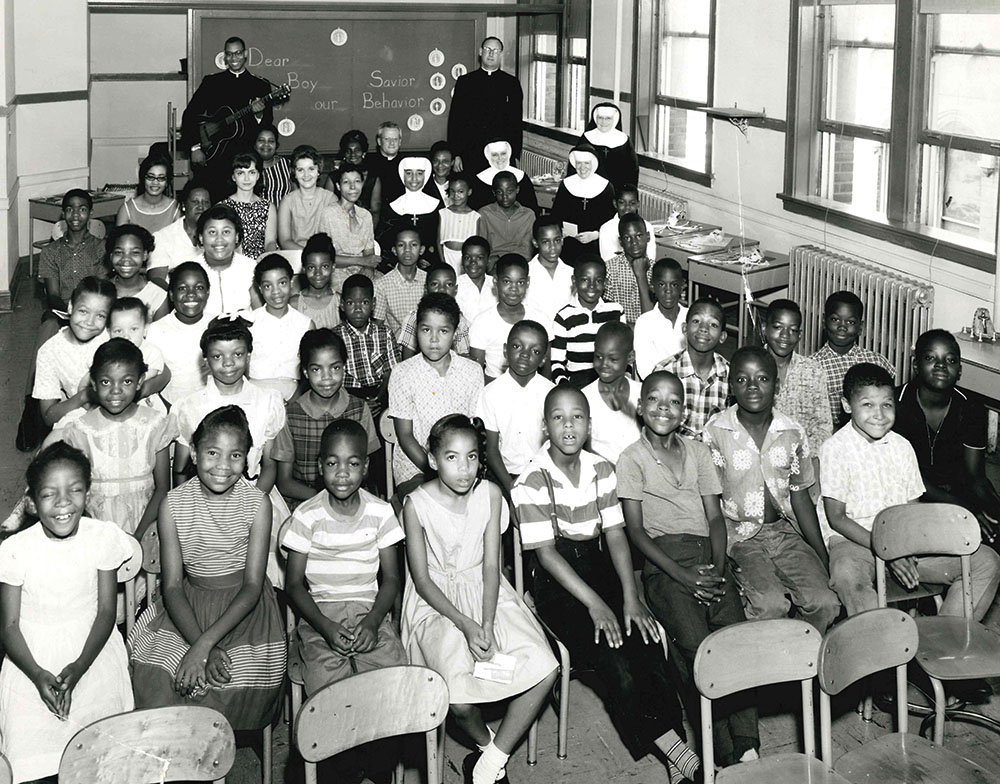

Lawrence Thornton, SVD, with St. Elizabeth youth, c. 1954. Thornton was the 30th Black priest ordained to the Divine Word fathers. He would later become pastor of Our Lady of the Gardens.

Corpus Christi’s pastor had wanted to open his parish to minister to Black Catholics as early as the 1920s. However, Mundelein adamantly maintained that Ss. Elizabeth and Anselm would be the only “ethnic” Black parishes for the South Side. The Franciscans were entrusted the shrinking and crumbling parish and were instructed to minister to the remaining whites. By the end of the 20s, both mass attendance and school enrollment at Corpus Christi dropped to less than 100. In 1932, after urging from Fr. Eckert, the cardinal saw the writing on the wall and gave the Franciscans permission to open the parish to the Black community. Seven years later, the friars were confirming over 500 adults at Corpus Christi.

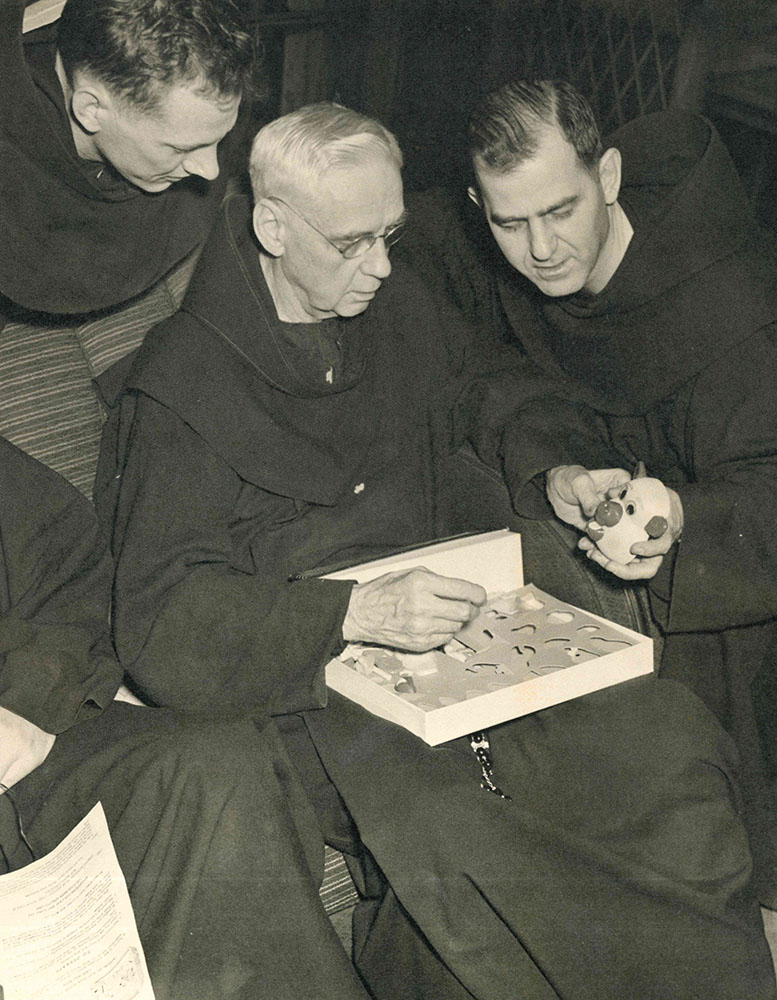

Franciscan friars enjoying a moment of fun at Corpus Christi, c. 1950s. From left to right: Frs. Benedict Hagen, Ernest Koufhold, and Maurice Amann, pastor. Koufhold earned renown and distinction in the city for serving as the chaplain of Cook County Jail for 25 years.

Holy Angels and St. Ambrose remained predominantly white through the first half of the twentieth century. Holy Angels’ school did not enroll its first Black student until the 1940s; in 1957, the number was 4. When the racial makeup of Washington Park and Kenwood shifted with the second wave of the Great Migration following World War II, Holy Angels and St. Ambrose—rather than delegated to a religious order such as Ss. Elizabeth, Anselm, and Corpus Christi had been—remained staffed by diocesan priests.

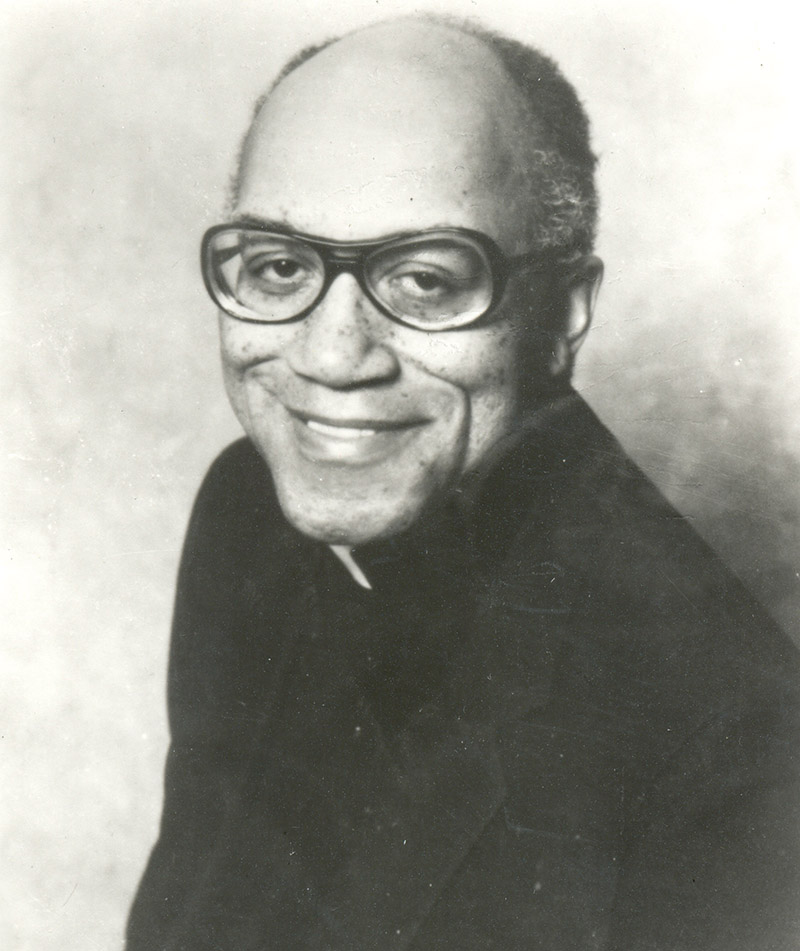

In 1969, Fr. George Clements was named pastor of Holy Angels. Clements was the second Black priest ordained by the Archdiocese of Chicago and had previously served as an associate at St. Ambrose and St. Dorothy. During the 70s and 80s, Fr. Clements brought national renown to Holy Angels for his tireless work promoting social and racial justice in the neighborhood.

In 1969, Fr. George Clements was named pastor of Holy Angels. Clements was the second Black priest ordained by the Archdiocese of Chicago and had previously served as an associate at St. Ambrose and St. Dorothy. During the 70s and 80s, Fr. Clements brought national renown to Holy Angels for his tireless work promoting social and racial justice in the neighborhood.

Velma Barker-Hill, who came to Holy Angels at age 19 after marching with Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in Mississippi, considered Fr. George a “genuine human being.” When her husband Michael converted to the faith and joined the parish in the 1990s, she remembers how overjoyed Fr. George was, taking him around the parish for a tour of all the buildings. Fr. Clements also paid a personal visit to their son, along with all his teachers, when he was in the hospital from a car accident. Those kinds of gestures made Velma and her husband feel like the parish really cared for their well-being.

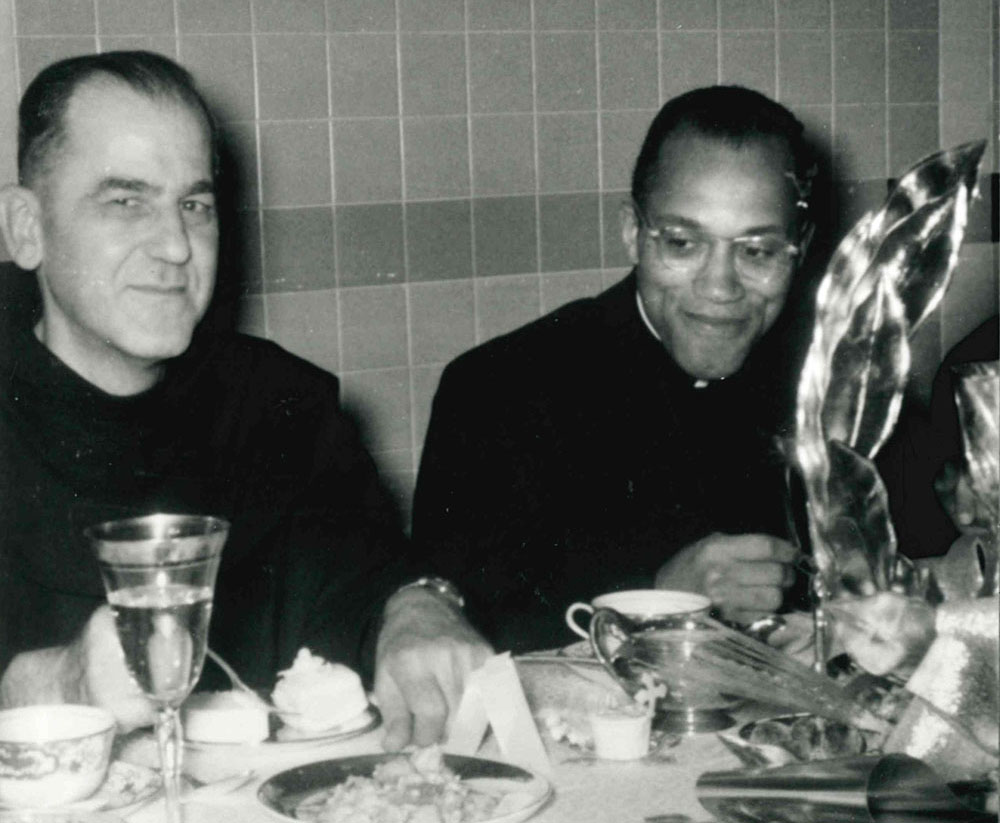

Fr. Maurice Amann, OFM and Fr. George Clements, celebrating at Corpus Christi.

In the booklet Beginning of An Era: History of the Work of the Catholic Churches among the Negroes of Chicago, Fr. Aloysius Zimmerman, SVD proudly noted that in 1952, 1600 Black adults had converted to the Catholic faith. Thirty years prior, that number was 35. What was behind this wave of conversion?

St. Elizabeth First Communion Class, undated.

“…the work [St. Elizabeth] has done since 1924 in its own little way is far more important and far-reaching than anything that was done before.”

-Fr. Aloysius Zimmerman, SVD, Beginning of An Era: History of the Work of the Catholic Churches among the Negroes of Chicago, 1952

Fr. Eckert and his predecessor Fr. Reissmann, had pioneered a system of adult instruction classes and vigorously pursued converts in a majority-Black neighborhood where most were not Catholic. The SVD and Franciscans took up their missionary work with zeal and determination, using any chance—whether it be at schools or funerals or weddings—to convince adults to learn about the faith at evening classes.

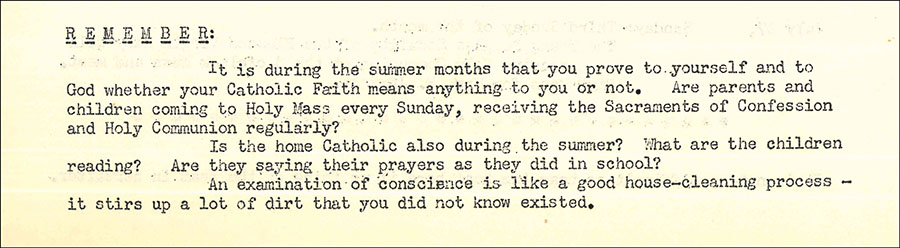

Joyce Lane, a longtime parishioner of St. Anselm’s recalls the SVD priests visiting her parents, who were both Baptist, when they enrolled her for first grade in the parish school. She remembers the SVDs asking questions about her father’s previous marriage (his first wife had died soon after the marriage) and setting requirements for her religious education. She was expected to be baptized within a year of schooling. The parents would have to attend Sunday mass at least occasionally. Joyce would have an “attendance card” signed by the priest to show that she had been going to church (even during summer vacation and trips out of town!). The parents accepted these requirements if it meant that Joyce would get a first-class education.

St. Anselm summer bible class, 1964, and an undated 1st communion photo.

The result? After Joyce and her sister were baptized, her mother followed soon after. She remembers how some years later, her father finally caved to the pressure, feeling “a little guilty eating meat on Fridays while we all ate fish.”

Corpus Christi bulletin, 1949.

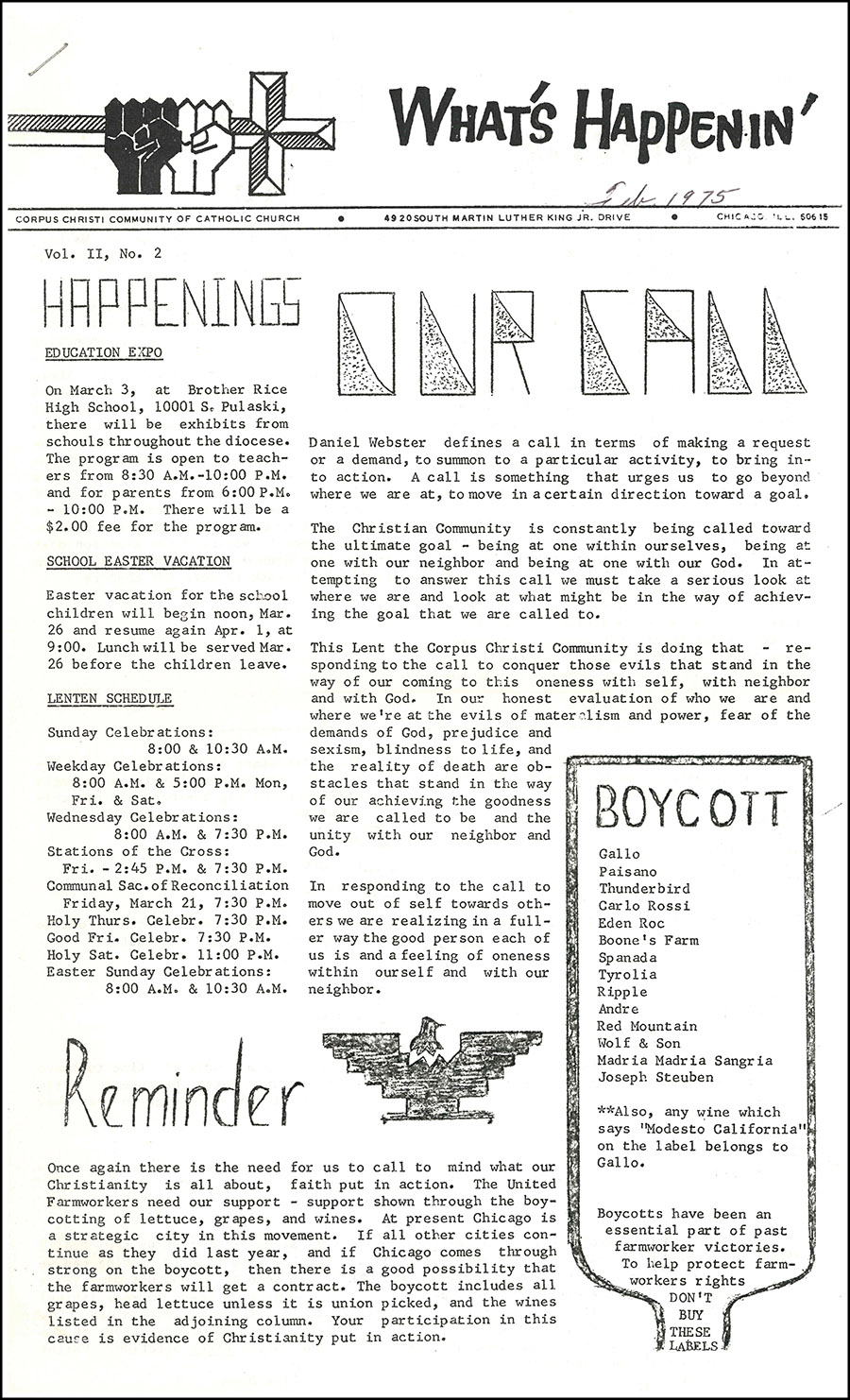

As parishes grew with families and converts, Black Catholics formed their own associations within the parish. These groups provided a sense of identity and community in the neighborhood, bound people together, and provided important social outlets for its members.

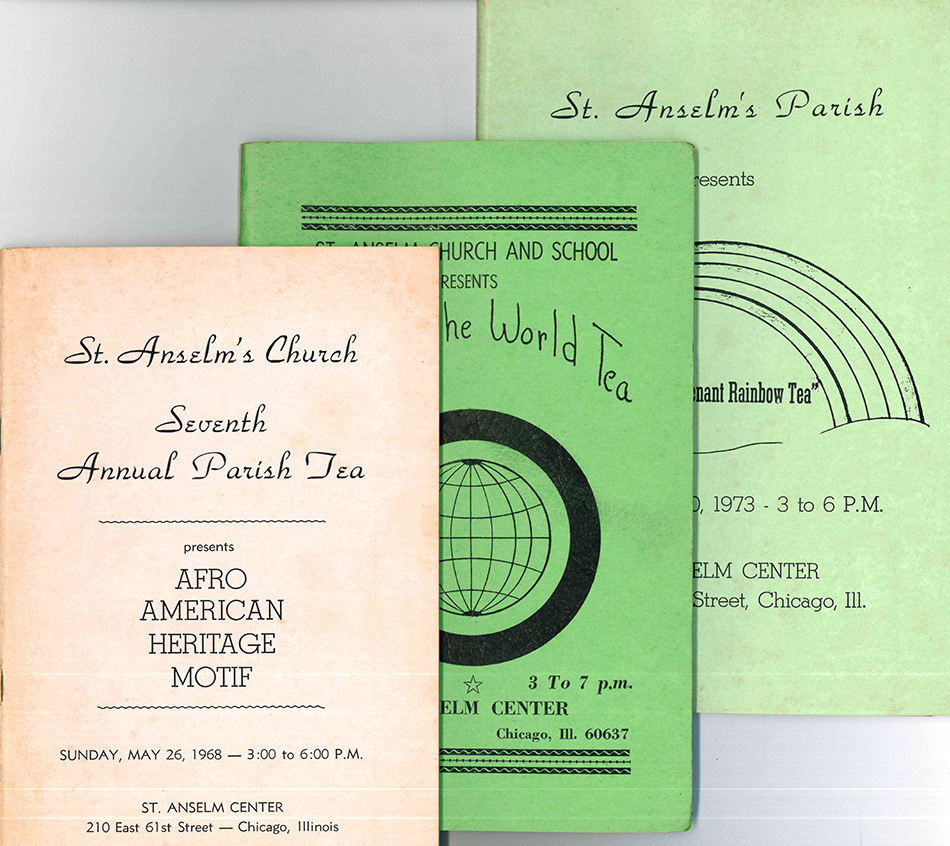

Credit Unions provided Black parishioners an opportunity to borrow and save money where other institutions would turn them away. The Knights of Peter Claver, counterpart to the Knights of Columbus (which at that time did not admit Black members), stood as honor guard for sacred ceremonies at the church and supported charities in the neighborhood. Scouting groups taught self-sufficiency and independence for young boys and girls. Devotional societies, sodalities, and youth groups added to the vibrancy of the parishes. These parishes were proud of their ministries, often listing their accomplishments in yearly programs, newsletters, and commemorative booklets, pictured below.

Credit Unions provided Black parishioners an opportunity to borrow and save money where other institutions would turn them away. The Knights of Peter Claver, counterpart to the Knights of Columbus (which at that time did not admit Black members), stood as honor guard for sacred ceremonies at the church and supported charities in the neighborhood. Scouting groups taught self-sufficiency and independence for young boys and girls. Devotional societies, sodalities, and youth groups added to the vibrancy of the parishes. These parishes were proud of their ministries, often listing their accomplishments in yearly programs, newsletters, and commemorative booklets, pictured below.

Parishes functioned as centers for the Black community to gather in their neighborhood where they were otherwise denied access. In 1951, Cardinal Stritch dedicated the St. Anselm Community Center, which became a popular for its large roller-skating rink and auditorium. Every year, St Anselm would put on skating shows and other plays in the center for the benefit of the neighborhood.

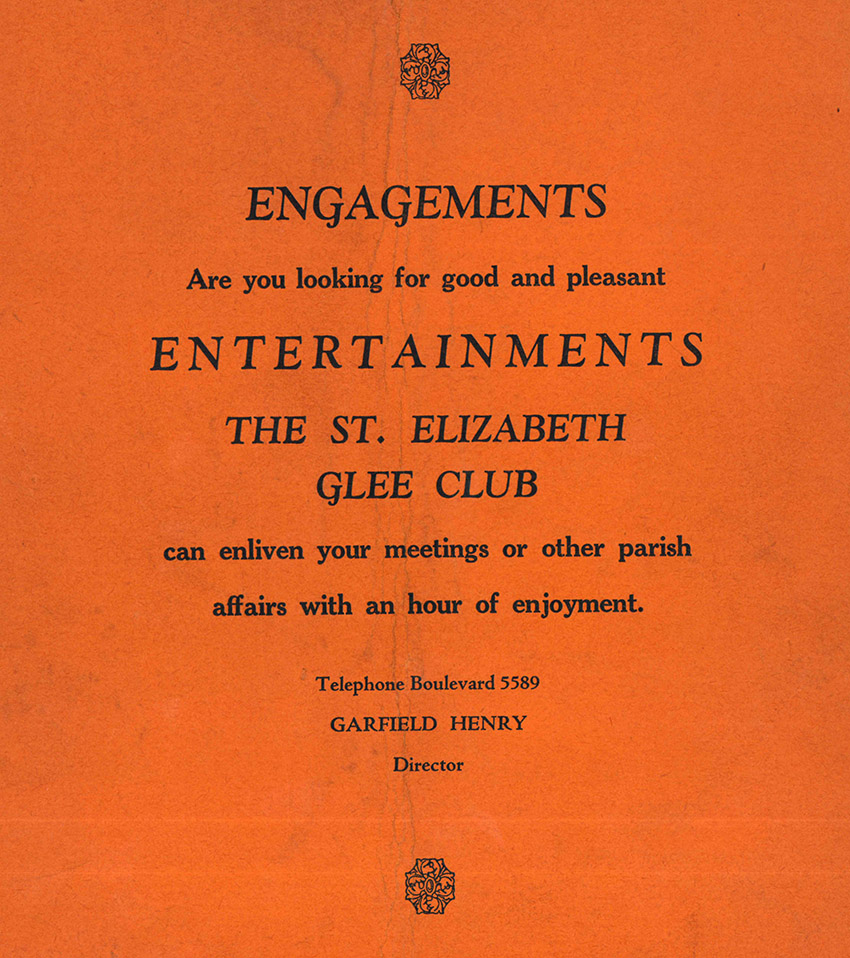

Music and singing within the parishes served an important social and religious role, with each parish often having numerous choirs and glee clubs specializing in different music. In 1944, Corpus Christi purchased the Sinai Temple building at 4620 S. Parkway and converted it into a special auditorium specifically for music performances. In one of the choir’s concert programs (pictured below), Fr. Rufinus Glauber, OFM stated that the area lacked a music hall of its own and that Corpus Christi would proudly step in and provide music for the South Side.

The Pastor’s Tea was a highly successful fundraiser for Corpus Christi and other parishes. Large and lavish program books would outline the work and improvements made to the campus, the number of converts from the previous year, the contributions of its various organizations and ministries, and display pictures of the King, Queen, and court picked from students at the grade school and high school. In the late 70s, the Tea transformed into the parish Fashion Show where the congregation could show off the latest trends and styles.

The Pastor’s Tea was a highly successful fundraiser for Corpus Christi and other parishes. Large and lavish program books would outline the work and improvements made to the campus, the number of converts from the previous year, the contributions of its various organizations and ministries, and display pictures of the King, Queen, and court picked from students at the grade school and high school. In the late 70s, the Tea transformed into the parish Fashion Show where the congregation could show off the latest trends and styles.

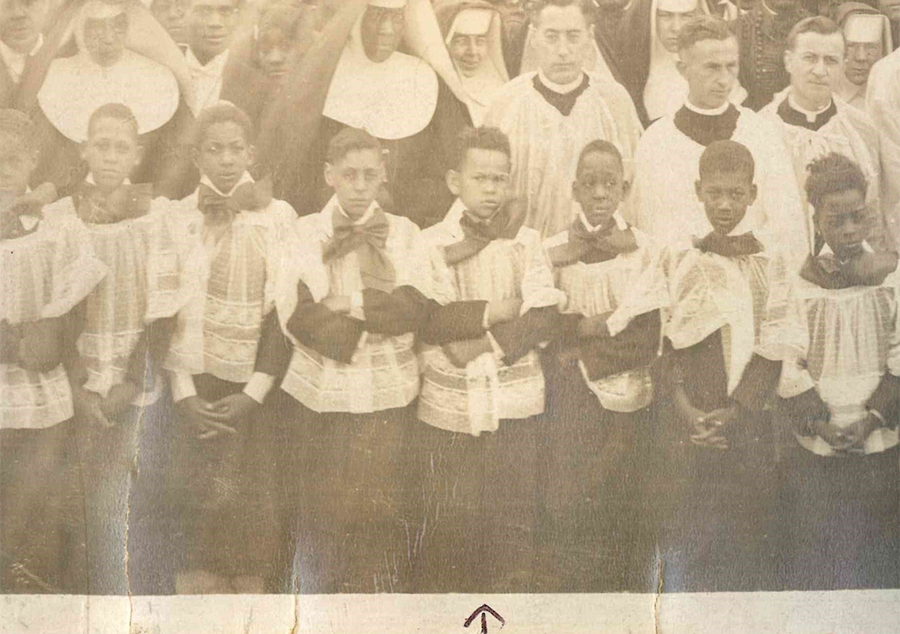

The Bronzeville, Washington Park, and Kenwood communities were never shy about showing off their faith, even in the early days of the neighborhood. When Chicago hosted the 1926 Eucharistic Congress, the effort was made to display the size and devotion of the Black community at St. Elizabeth. At the time Fr. Eckert had amassed a Holy Name Society of over 500 men, and nearly the entire parish turned out to come and see the distinguished guest Fr. Norman DuKette, at the time one of five Black priests in the United States. A crowd estimated between ten and twenty thousand, Blacks and whites alike, gathered at St. Elizabeth for the Congress.

Identified in this closeup is Joseph Robichaux Jr., a St. Elizabeth Altar Boy who later ran the neighborhood’s Catholic Youth Organization building.

“When I was a small boy in the late 1940s, my mother took me to Corpus Christi to see the Living Stations of the Cross during Lent. She said they were the most beautiful stations I would see anywhere, and they were.”

-Francis Cardinal George, 2001

Corpus Christi first staged a live reenactment of the Lenten Stations of the Cross in 1937 under the direction of Fr. David Fotchman, OFM. Everything from the costumes and sets were designed and made by the congregation. The cast was made of parishioners, who performed and pantomimed the stations while one of the parish priests narrated the Passion. This proved to be a popular yearly production for the parish and neighborhood.

The Living Stations grew in renown and attracted attention from its appearances in newspapers and the Catholic Extension magazine. In 1957, WGNTV televised the reenactment in a program called Faith of our Founders several times. While this brought further fame to the parish, a contemporary chronicler noted that the cast and crew found the TV directors—who insisted on adding more drama and action into the pantomime—onerous. The cast preferred to keep the Living Stations a live—and local—production. Pictured here are scenes from one of the 1950s productions.

“Experts in stage art, unable to explain the phenomenal success [of the Living Stations], attributed it to the cultural heritage of African Americans: that fathomless depth of feeling and endurance characteristic of the African American race. It was believed that only a people with a history of having been torn from their native Africa, stored in slave pens, sold at auction blocks, reduced to slavery, suffering and degradation, could fully identify with the Gospel characters.”

-Corpus Christi: A Hundred Years of Faith, 2001

Corpus Christi attracted its fair share of dignitaries over the years, including Bishop Joseph Kiwanuka of Uganda in 1951. Kiwanuka was the first native African bishop in the Catholic Church. And Bishop Fulton Sheen, whose popular television program Life is Worth Living reached millions of viewers a week, came to Corpus Christi in 1954 to see the production of the Living Stations and preach. A crowd of thousands thronged outside the church to see the popular bishop. Tickets had to be purchased in advance just to attend Mass.

After the Second Vatican Council, liturgy and devotion took on new forms in the community. Masses became more intimate, music styles shifted, and more African spiritual motifs were integrated into the divine liturgy. While some missed the older, solemn mass, Edith Rutledge Lane, a parishioner of St. Elizabeth parish, welcomed the change at the time. She recalled how she was happy how the liturgy, before cold and stoic, now burst forth with life and movement.

“[St. Elizabeth] is the outstanding parish in the United States and its school second to none. It is a personal distinction to belong to this church and to the Catholic Church.”

-George Cardinal Mundelein, 1926

The parishes of Our Lady of Africa considered their schools as the main driving factor in growing the Catholic faith during the first half of the twentieth century. The schools expanded rapidly, often with non-Catholic students. Parents were attracted first and foremost to what they saw as the superior schooling of the Catholic education system, especially compared to the underfunded and segregated inner-city public schools.

The original sisters who taught in the area were the Sisters of Mercy. When the white student population plummeted, but before the schools were opened to Black pupils, the Sisters of Mercy found themselves managing empty schools; this untenable situation forced them to leave. Upon their arrival, SVDs sought out the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament, while the Franciscans at Corpus Christi and Holy Angels enlisted the School Sisters of Saint Francis. Over time, St. Elizabeth and Corpus Christi would open nearby high schools to continue to cultivate their children as they matured into adulthood.

Edith Rutledge Lane, whose children attended St. Elizabeth grade school in the 1970s and 1980s, credited the school’s many concerts, plays, and public speaking contests with giving her daughter the confidence and ability to speak to a crowd (unlike some of her daughter’s classmates, the young girl took the contests quite seriously). Edith herself would assist in producing and organizing plays for Black History Month at the school, crafting short plays about saints and religious figures that would be played out by both students and adults.

Joyce Lane, who graduated St. Anselm in 1960, fondly recalls the education she received from the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament. According to her, the sisters cultivated a “we can do this” feeling in their students: “We could master any subject [if we set our minds to it.]”

As Joyce reflected, she noted that more importantly the sisters at that time prepared the young men and women on what they would need to do to integrate into a larger society, once they left the “nurturing environment” of St. Anselm’s. The students spent their 8th grade years learning about how to survive the prevailing racist attitudes in mixed society, and how to thrive despite them. She, like many others, would credit the sisters with preparing her and her friends for their future success.

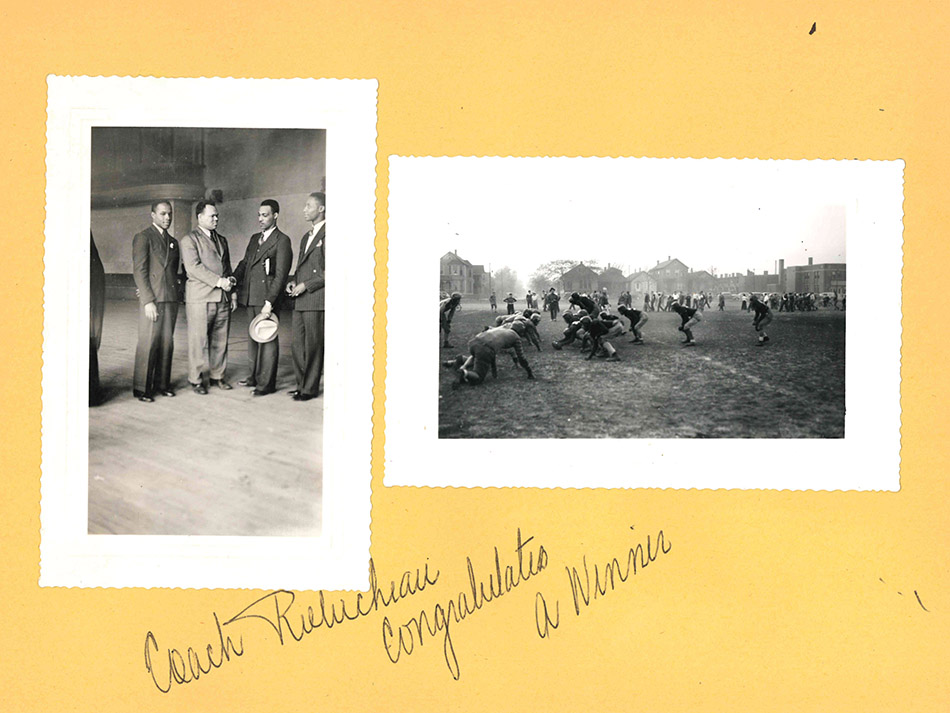

Sporting teams and clubs were an important fixture in the neighborhood. Groups like the CYO and the school teams gave parish children and teenagers a means to grow as athletes and as human beings. School sports also gave them a chance to compete across the city in various Catholic leagues, which provided students with opportunities to see other parishes in Chicago and play against schools both Black and white.

Outside of the schools, the Catholic Youth Organization (CYO) provided additional ways for young Black men and women to excel as athletes and grow as people. In the 1930s and 40s, Bishop Bernard Shiel wanted to use the CYO partially as a means of integrating white and Black Catholic teenagers and breaking down racial barriers in the city. During this time, the neighborhood CYO building, known also as the Shiel Center, was administered by a former St. Elizabeth altar boy, Joseph Robichaux Jr., present at the Eucharistic Congress decades earlier.

Left: The CYO Lightweight Team, 1940. Pictured with the athletes are Fr. Joseph Eckert, SVD (left), pastor of St. Elizabeth Fr. William Brambrink, SVD (center), and Joseph Robichaux (right). Right: scenes from St. Elizabeth football, circa 1930s-40s.

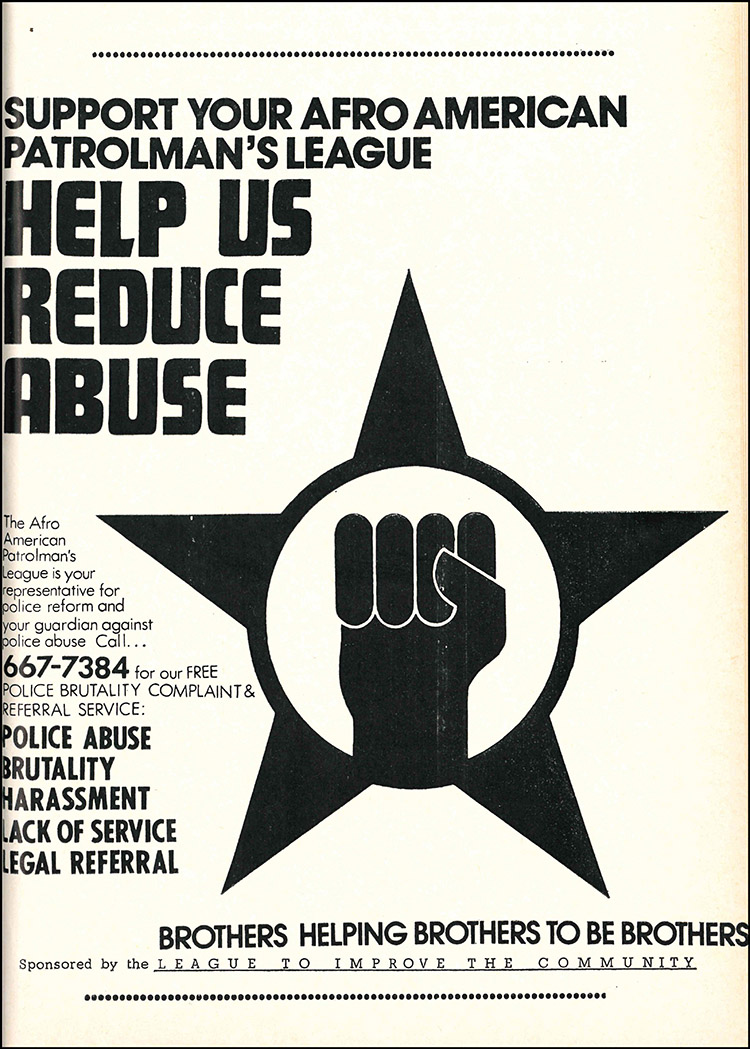

After the 1960s, Bronzeville, Washington Park, and Kenwood started to undergo a drastic change. Many of the middle-class residents moved out, making the area poorer. Unscrupulous landlords cut up and compartmentalized the older, larger homes, cramming families into small apartments. Over time parishes had to reckon with the effects of this shift, in drug and gang violence. The parishes responded to these changes, often taking more overtly activist and political stances on issues of the day.

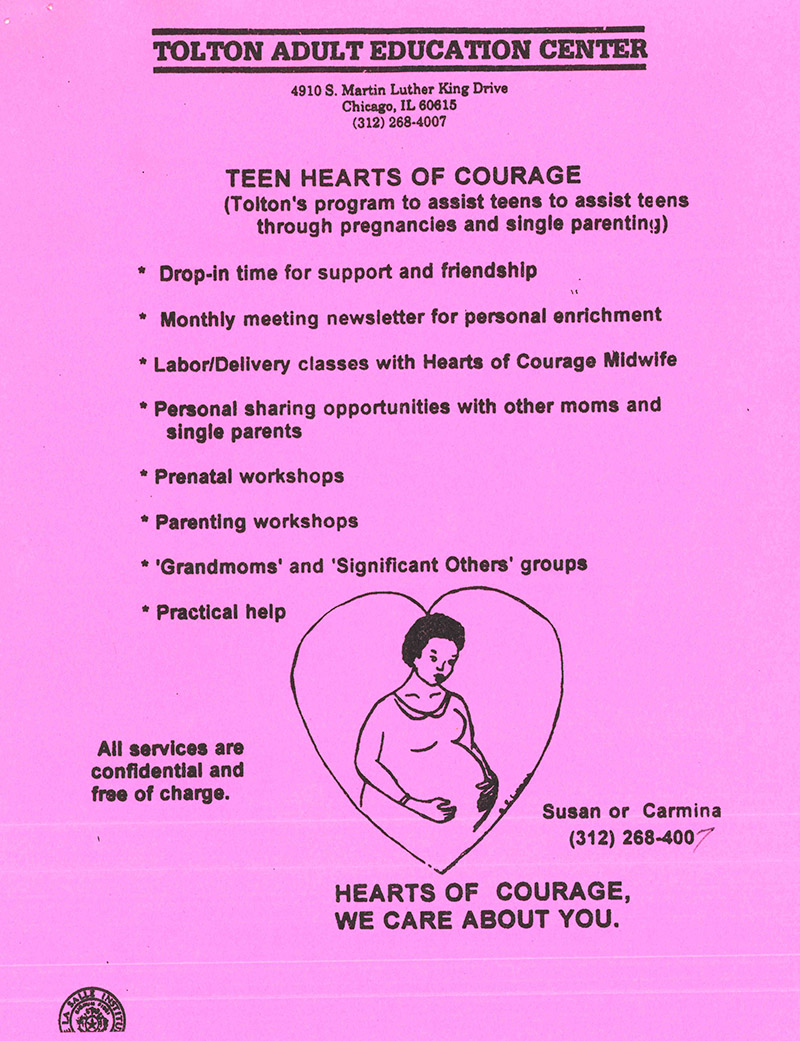

In the 1990s, one Corpus Christi parishioner felt called to bring a new light into the neighborhood. Dr. Olukemi Ebunoluwa worked daily ministering to single mothers in the nearby Robert Taylor projects. These women were often abandoned, poor, or struggling with the fallout of gang violence and addiction. Dr. Olukemi wanted to bring a new symbol of hope into the South Side. That symbol would be Our Lady of Africa.

In the 1990s, one Corpus Christi parishioner felt called to bring a new light into the neighborhood. Dr. Olukemi Ebunoluwa worked daily ministering to single mothers in the nearby Robert Taylor projects. These women were often abandoned, poor, or struggling with the fallout of gang violence and addiction. Dr. Olukemi wanted to bring a new symbol of hope into the South Side. That symbol would be Our Lady of Africa.

She commissioned a local diocesan artist, Fr. Anthony Brankin, to design a bronze statue for Our Lady. The design was based off an existing statue dedicated to Our Lady of Africa in Algiers, Algeria, which was venerated by Christian and Muslim alike in the basilica at the heart of the city, but with a decidedly more African likeness. The parish connected the statue to the movement “One Mother, Many Titles,” showing the miraculous power of Mary all over the world.

The statue of Our Lady of Africa at the Holy Angels site, taken 2021.

At the 1996 dedication of the statue, Dr. Ebunoluwa drew parallels from the life of Mary to the women she served at the Robert Taylor homes and elsewhere. These women, like Mary, had to raise their children in a violent world and without support. She hoped that the statue would promote racial healing and provide a way for the neighborhood to beseech Mary for her intercession and protection.

At the merging of Corpus Christi with the other four parishes in Bronzeville, the statue of Our Lady was moved into the church of Holy Angels, welcoming those who entered the church. The new parish was named Our Lady of Africa, administered by the Society of the Divine Word.

The end of this era filled many with sadness to be sure. This sadness is natural, given the strong legacy and history of these historic Black parishes. Speaking with some of the longtime parishioners of these churches, they see the need for change and reasons for hope. They see a need for the Catholic community to become active in their neighborhood more than ever, pursuing Christian ideals of faith, solidarity, and social justice. They see the need for the Church to engage with the youth in an authentic way, to remember Fr. Eckert’s mantra to be “kind and charitable to all.” And they feel a hope that by coming together, their history, their lived experience, and their faith in God will shepherd the Black Catholic community into an unknown, but grace-filled future.

The Archives and Records Center is thankful for the help and cooperation of parish staff, volunteers, and local historians to preserve and share the remarkable story of these parishes. It is part of our mission to enshrine the stories of these faith communities for future generations.

Researched and Written by Charles Heinrich, CA. Charles received his MA in History from Loyola University Chicago in 2015 and is an Archival Technician at the Joseph Cardinal Bernardin Archives and Records Center. Charles is the author of Song in Stone: A History of Madonna Della Strada Chapel and Service, Sacrifice, Scholarship: 100 Years of Preparing Social Work Leaders.

Historical Materials and Oral History Coordination provided by Tina Carter, MLIS/MDiv. Tina is a parishioner of Our Lady of Africa and is part of its historical committee whose aim is to share and celebrate the legacy of Black Catholicism in Chicago. She serves as the Branch Manager for the Brighton Park Public Library.

Barker-Hill, Velma. Interview by Charles Heinrich. Oral history interview. Chicago, IL. February 3, 2022.

“Chicago Priest Assigned to Gold Coast Diocese.” Jet. July 14, 1955.

Corpus Christi: A Hundred Years of Faith, 1901-2001. Chicago: 2001.

Historical Records – Christi Parish and School (King Dr.). Joseph Cardinal Bernardin Archives and Records Center (Hereafter Archives and Records Center), Archdiocese of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

History Records - Historical Records - St. Ambrose Parish (47th St.), HIST/H3300/486. Archives and Records Center, Chicago, IL.

History Records - Historical Records - St. Anselm Parish (Michigan Ave.), HIST/H3300/503. Archives and Records Center, Chicago, IL.

History Records - Historical Records - St. Elizabeth Parish (41st St.), HIST/H3300/492. Archives and Records Center, Chicago, IL.

Jackson, Angela. Ain’t Gone Lay My Religion Down. Chicago: 1997.

Koenig, Harry C. (Msgr.), Ed. History of the Parishes of the Archdiocese of Chicago, Volume I. Chicago: Catholic Bishop of Chicago, 1980.

Lane, Joyce. Interview by Charles Heinrich. Oral history interview. Chicago, IL. January 28, 2022.

Neary, Timothy B. “Crossing Parochial Boundaries: Interracialism in Chicago's Catholic Youth Organization, 1930-1954.” American Catholic Studies. Vol. 114, No. 3. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44194804 (Accessed January 28, 2022).

“Pickin’ Cotton, Chicago Style: A Historical Digest of Chicago: Black and Catholic, 1880-1980.” Unpublished Thesis, ca.1980.

Rhodes, Helen K. “An Historical Analysis of the Racial, Community, and Religious Forces in the Development of St. Monica’s Parish Chicago, 1890-1930,” PhD Diss., (Loyola University Chicago, 1993).

Rutledge-Lane, Edith. Interview by Charles Heinrich. Oral history interview. Chicago, IL. February 1, 2022.

Souvenir Book of the Dedication of Corpus Christi Church. Chicago: Clark-McElroy Publishing, 1916.

St. Anselm’s Church: Souvenir Volume of Dedication. Chicago: 1910.

Zimmerman, Aloysius, SVD (Rev.). The Beginning of An Era: History of the Work of the Catholic Church among the Negroes of Chicago. Chicago: 1952.