Fr. John Beyenka

Introduction

A priest is an ordinary man called to live an extraordinary life.

He can be many things: a teacher, a counselor, a leader, an evangelist… But he is sent, at a particular time and place, to use his talents to minister to the needs of God’s people. At the Joseph Cardinal Bernardin Archives and Records Center, we want to share some of the stories of local archdiocesan priests with you.

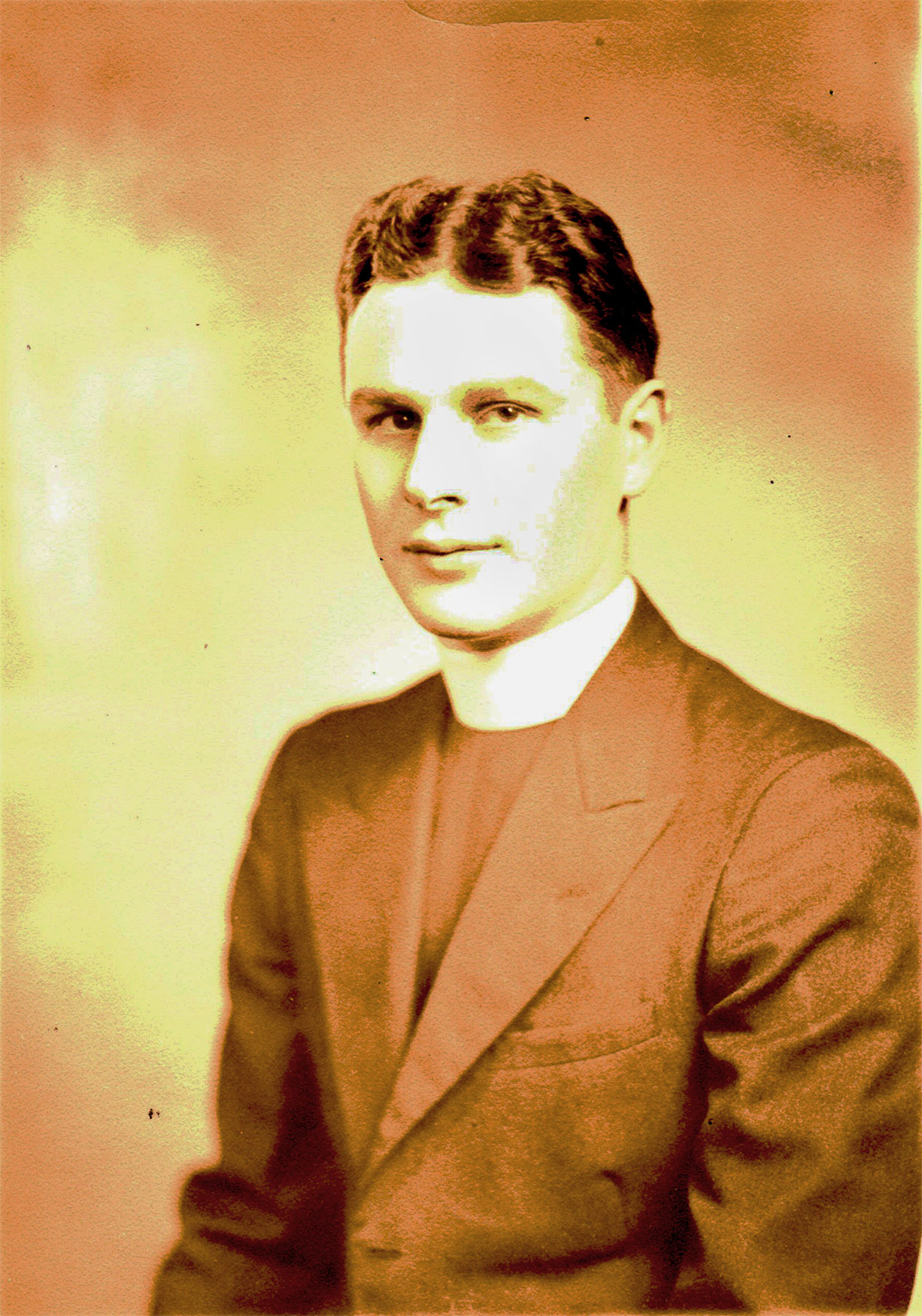

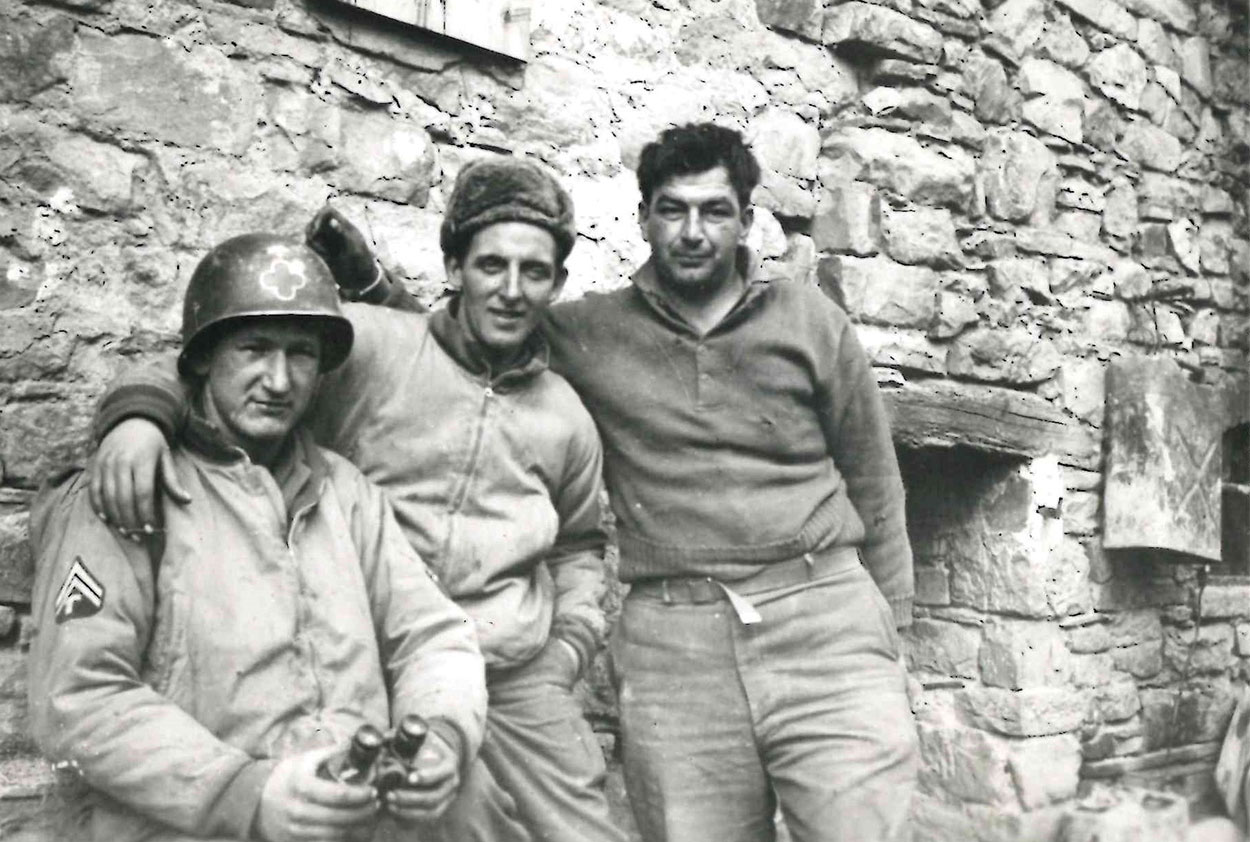

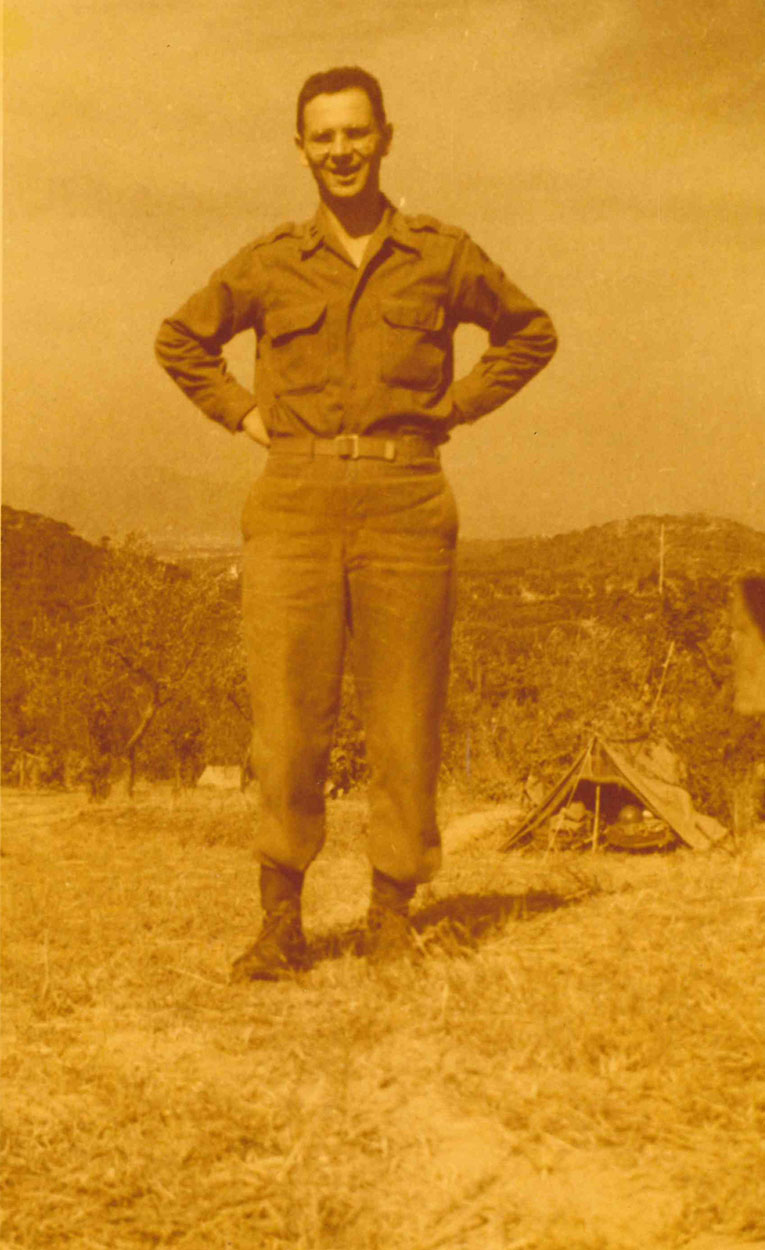

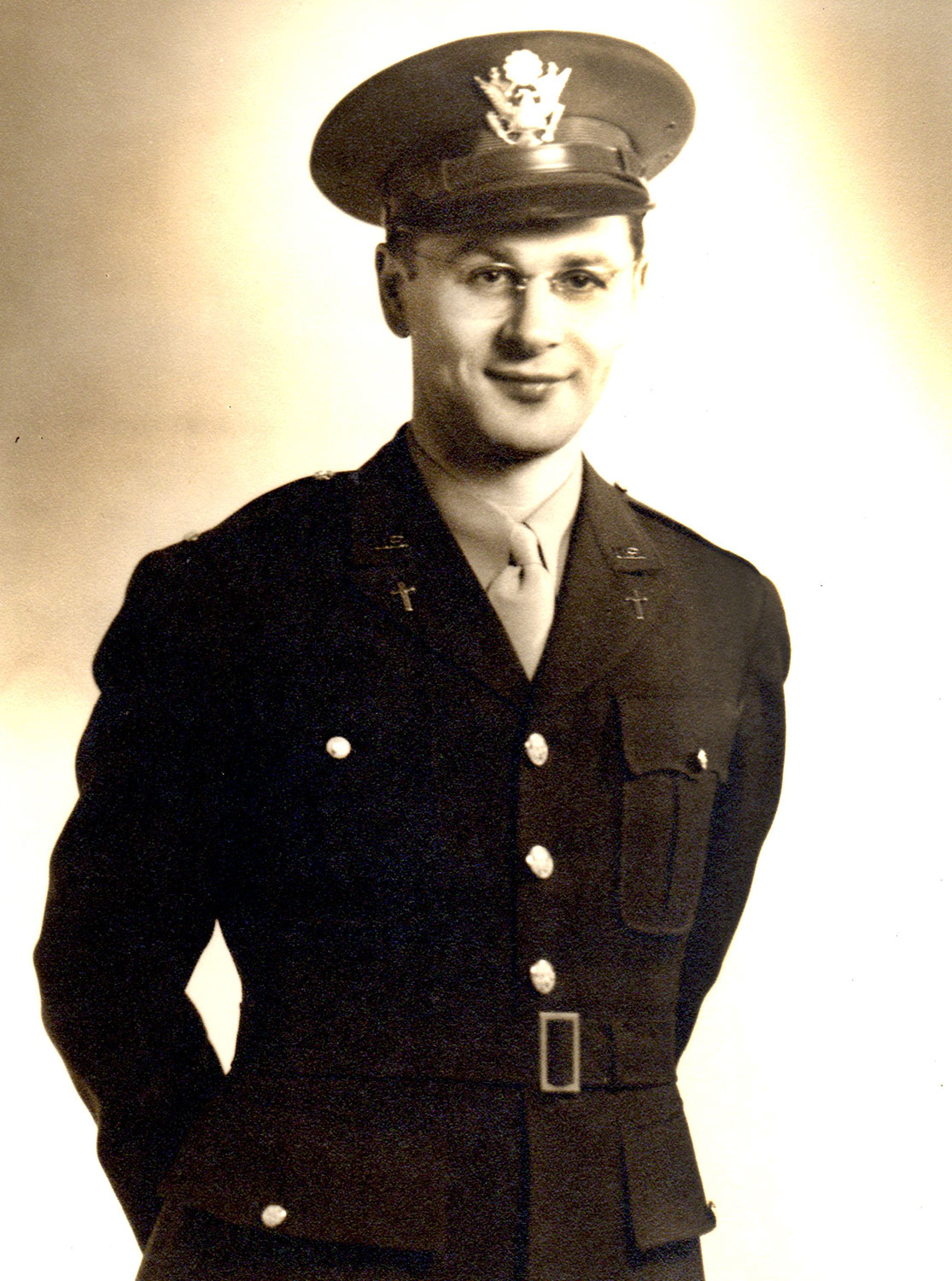

This story focuses on Fr. John Beyenka (1912–1998), a lifelong diocesan priest who became a World War II chaplain and saw up-close the horrors of war during the Allied invasion of Italy. Fr. Beyenka saved his wartime memorabilia—his daily letters home, his scrapbooks of army photographs, his pins and patches—and these were donated to the Archives after his death. They form the basis of this exhibit.

We want to encourage more diocesan priests to save their papers, photographs, and ephemera and consider giving them to the Archives. That way, their remarkable stories, their formation and ministry, can continue to inspire in the Archdiocese of Chicago and beyond.

Early Life and Vocation

John Thomas Beyenka was born on October 2, 1912 in Duluth, Minnesota to Thomas Beyenka and Leona Poull, the second oldest of six children. When John was four years old his father, an easygoing traveling salesman, moved the family to Chicago to look for work. The Beyenkas moved around Chicago’s North Side before joining St. Bartholomew Parish.

Faith played a large role in shaping the Beyenka household. Thomas Beyenka was never successful as a salesman, but he was an ardent Catholic and an accomplished tenor in his church choir in Duluth. Thomas spent summers scraping together extra cash beekeeping for his sister, Mother Eustacia Beyenka, OSB. Mother Eustacia founded the Mount Saint Benedict Monastery in Crookston, Minnesota in 1919. Thomas and Leona, despite numerous financial difficulties, sent all their children to Catholic school.

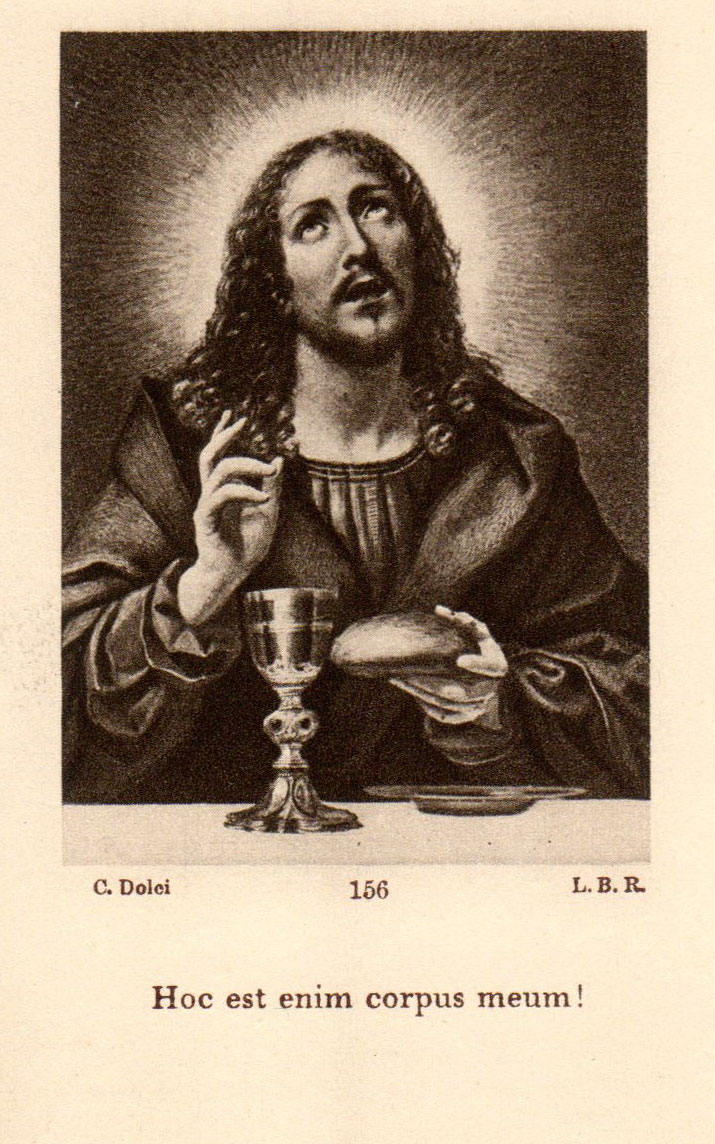

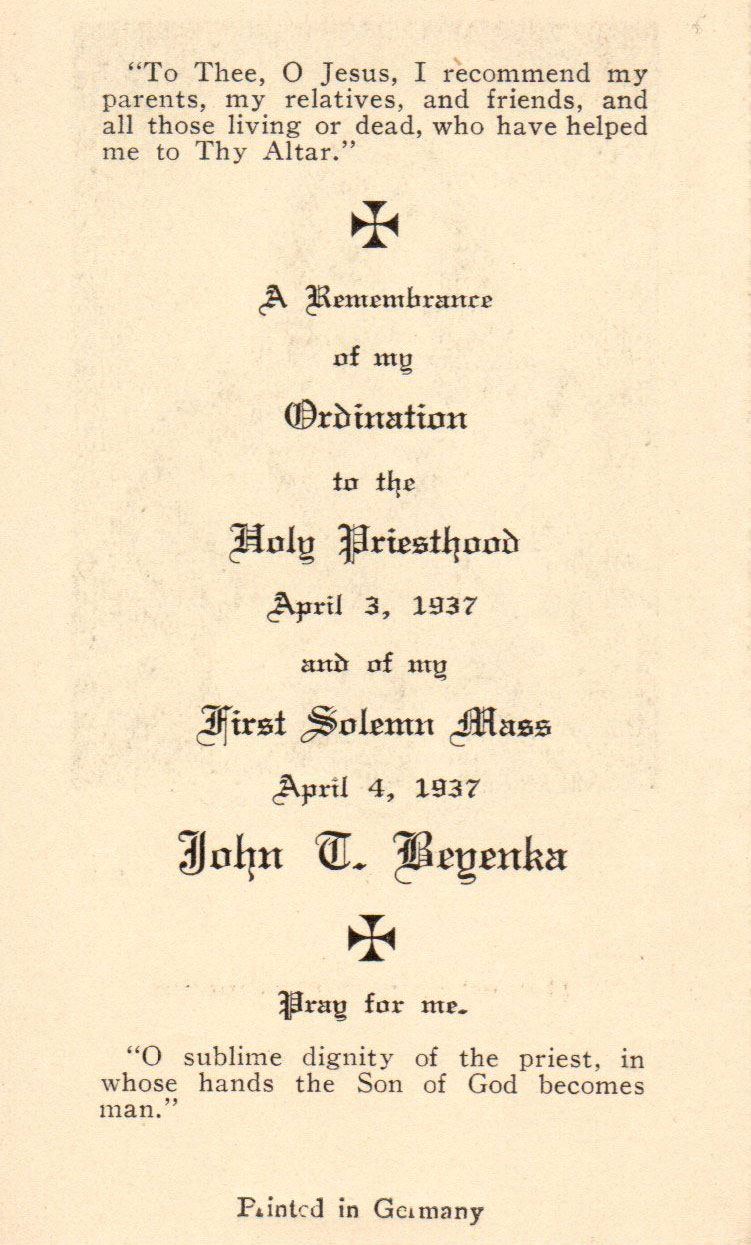

John and his older sister, Barbara, heard the call to religious life. Barbara went to Rosary College (now Dominican University) and took vows as a Dominican sister. John felt drawn to the priesthood and attended Quigley Seminary for high school, graduating in 1931. From there, John joined Mundelein Seminary, growing in his vocation before being ordained a priest in 1937 by Cardinal Mundelein. His first assignment was at Sacred Heart Parish on 19th and Peoria. For six years, Fr. John Beyenka lived the life of a parish priest, saying masses, administering the sacraments, and helping out at the local school.

A Second Calling

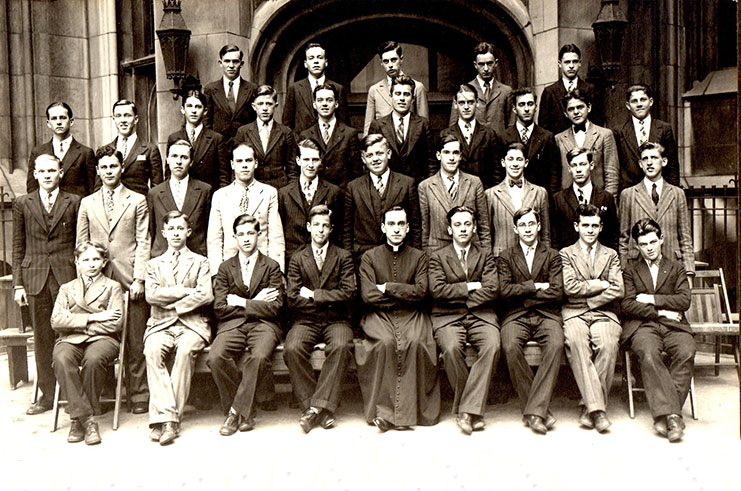

Fr. John Beyenka and other Catholic Chaplains gather for a class photograph. John is standing in the second row from the top, fourteenth from the left.

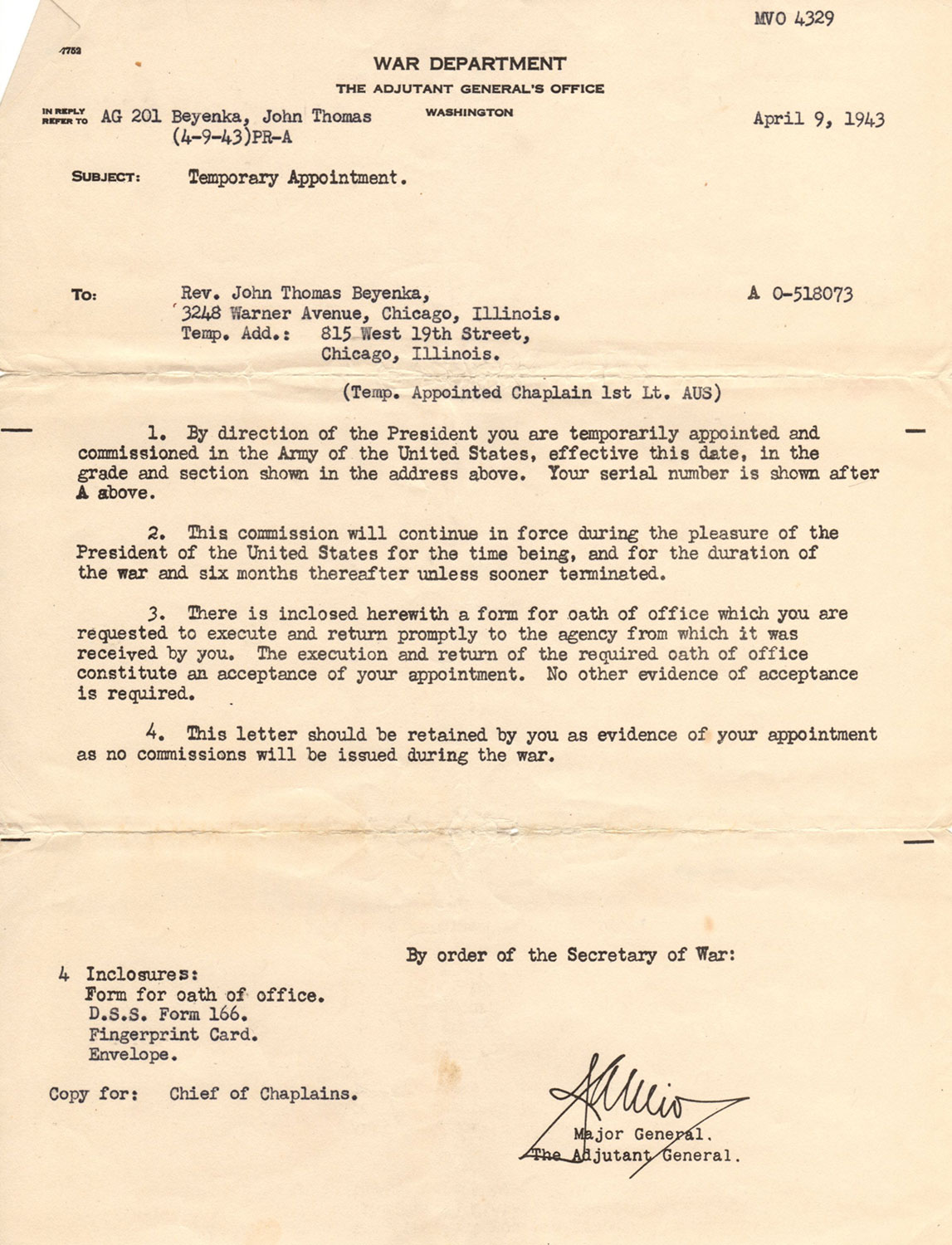

Two years after his ordination, World War II ignited around the globe. As the United States was drawn into the conflict, men rushed to enlist—or were drafted. In 1943, Fr. John decided to join the war effort and enlisted himself.

Why? Fr. Beyenka’s nephew, Fr. Michael Meany, recalls his uncle telling him that he had seen all the young men in his neighborhood leaving to go to war. A realization slowly dawned on him then. These men were going far away, and they were going to need a priest to be with them and serve them. And Fr. Beyenka decided that he would be that priest.

“There’s a feeling of importance that comes to me now. … My part may be small but added to all the others it means that the sacrifices of many will not be in vain. More than all this my motives are purely spiritual. If I can witness Christ to the men I’ve been attached to, it’s what I’ve been ordained for. Ignatius, the soldier of Christ, used to say da mihi animos cetera tolle [Bring souls to me, take away the rest]… all else means little – the dangers, cold, anxieties, fear, everything is just means for me to win souls for Christ.”

Fr. John Beyenka, letter to his parents, November 11, 1943

In the gallery below John is given his first orders as a 1st Lieutenant chaplain in the Army. Here he shares a photo with his mother Leona in his fresh new uniform.

Basic training took place first in Louisiana, then at Fort Sam Houston in Texas. Fr. John described a constant routine of drills, maneuvers, capture-the-flag exercises and marching. Despite the sweltering heat, Beyenka slept with his clothes on in the hopes that the next morning he would be covered with slightly fewer mosquito, tick and chigger bites.

Even during basic training Fr. Beyenka exercised his duties as chaplain. He said mass for the men along with the other chaplains, baptized converts (a task he was very proud to carry out), performed marriages, and offered confessions and spiritual counseling for the other men in his battalion. Fr. Beyenka enjoyed the lifestyle of basic training, as hard as it was; he relished the opportunity to grow closer with his own unit. In a letter home, he figured that “the men like to see the chaplain out with them and not in the chapel all the time.”

“Don’t look now Fuehrer, but here come thousands more of us.”

Ed Morgan, Chicago Daily News, 1943

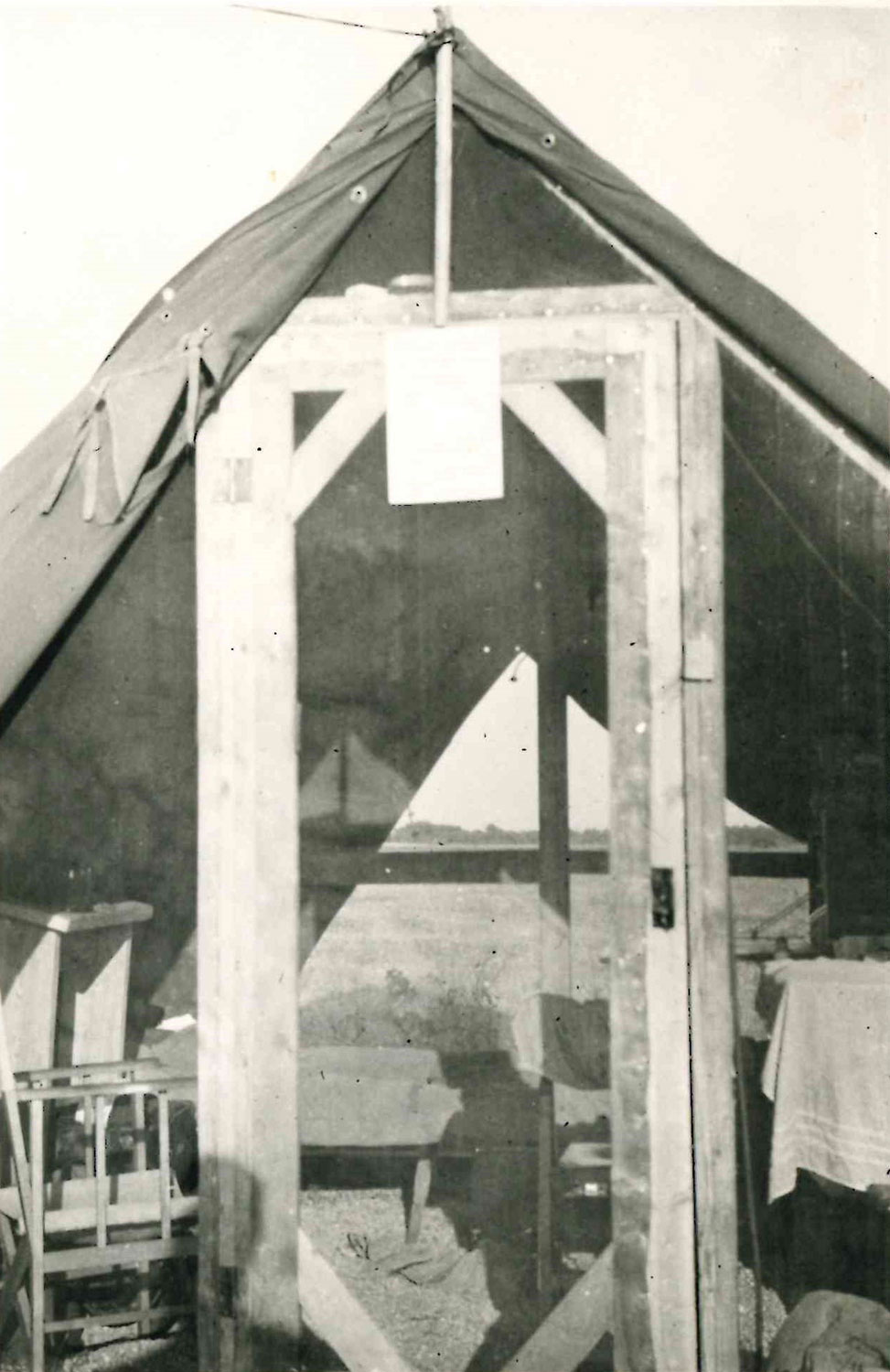

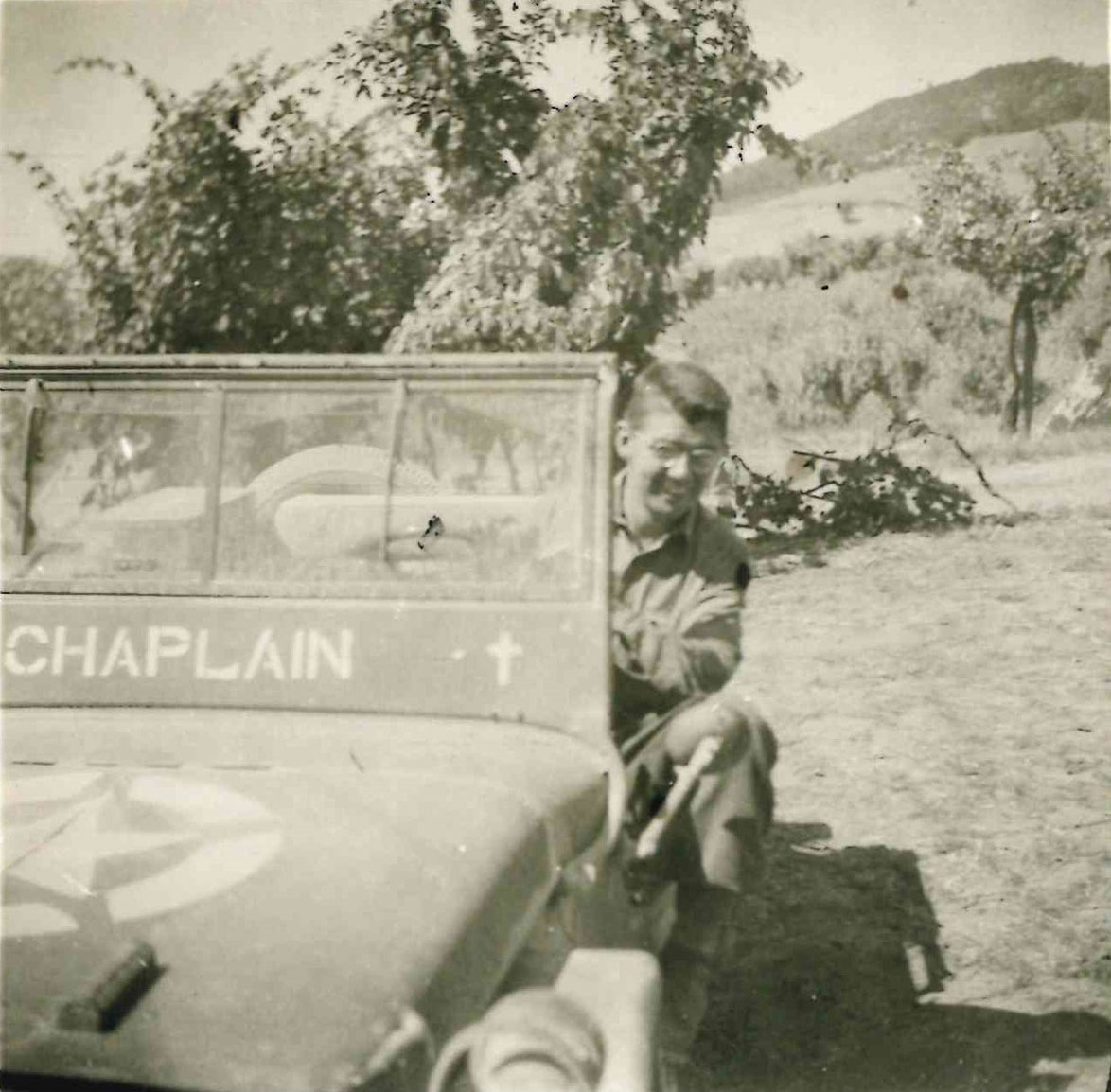

Fr. John worked with other chaplains in the regiment tending to the spiritual needs of his men, with particular care made to serve the sacramental needs of the regiment’s Catholics. His tent was his “office” with the materials and vestments needed to say the mass. He also had his own army jeep and driver to move quickly around the division.

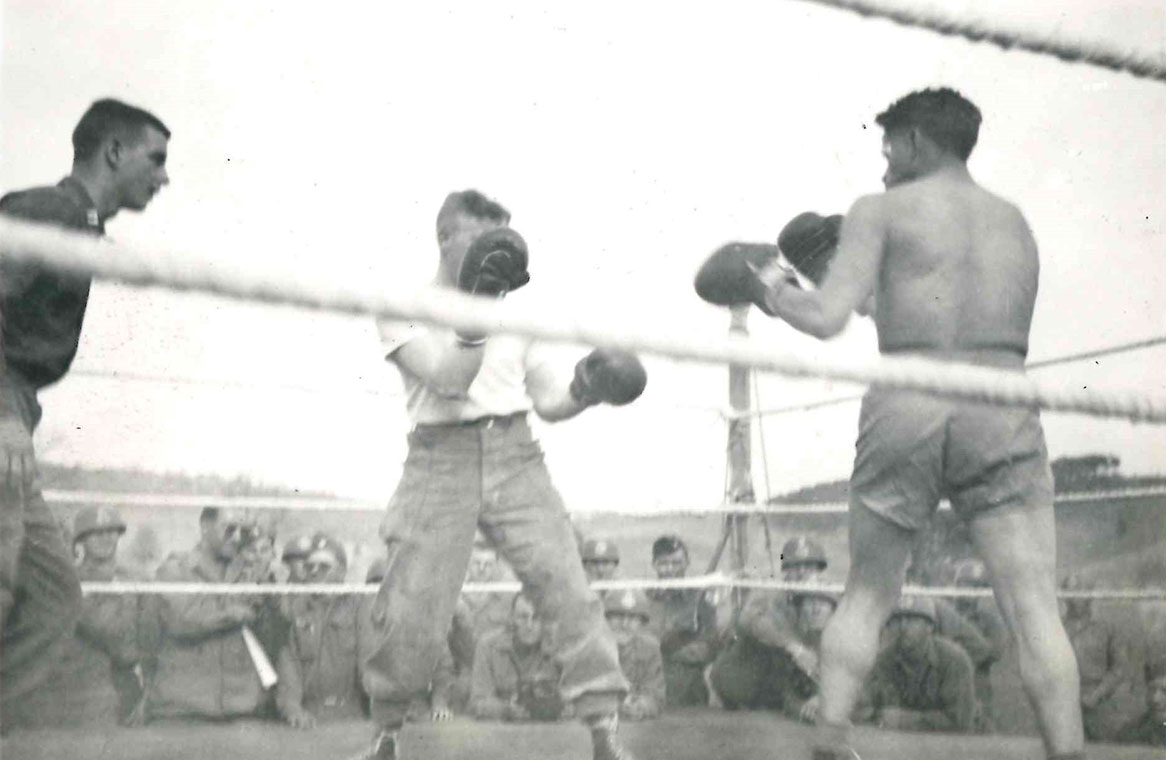

Not all of Fr. Beyenka’s obligations revolved around the chaplaincy. As a soldier who did not perform combat duty, John found himself in a variety of small roles, from medical transporter to mail censor and entertainment emcee. He was often called on to organize movie nights or boxing matches for the men of the battalion—the latter of which was a particularly popular pastime.

Pictured below are some of John Beyenka’s patches and pins from the war. Top left: the insignia of the 88th infantry division. The two 8’s were arranged into a clover shape, giving them one of their nicknames, the “Cloverfield Division.” Each division had their own unique insignia (compare with the 33rd’s “Golden Cross Division” below). Top right: the patch of the 5th Army. The A5 is housed in a Moroccan mosque, symbolizing the activation of the Army’s campaign in North Africa. Bottom: one of two lapel cross pins that would have identified Fr. John as a chaplain (see his uniformed portrait above).

Duties as a Chaplain

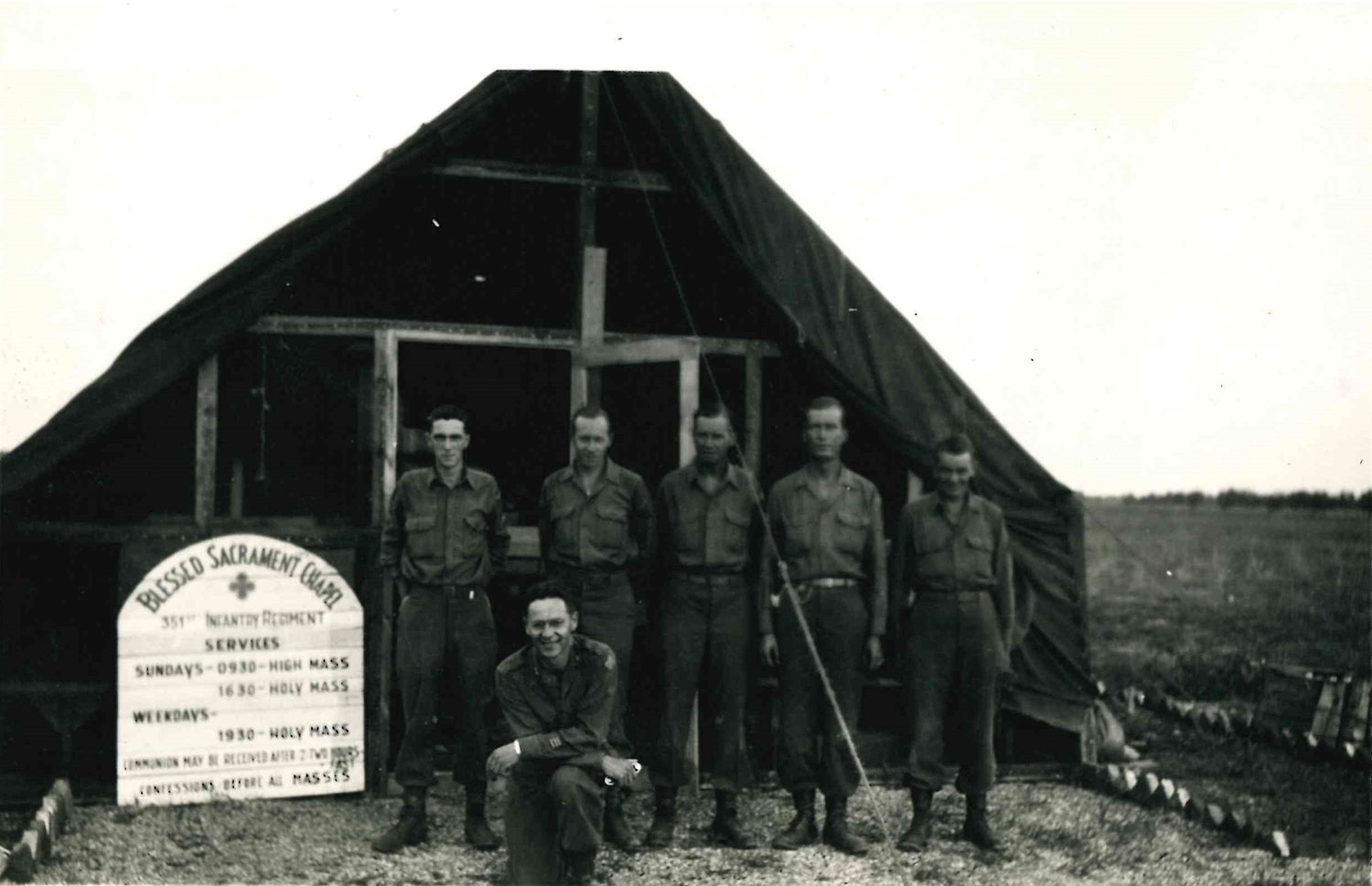

Fr. Beyenka (kneeling) and the other Catholic chaplains pose in front of the Blessed Sacrament Chapel, which they constructed themselves.

When Fr. John Beyenka became a chaplain in the army, he joined what is known as the Military Ordinariate. During World War II, Archbishop Francis Spellman of New York oversaw a ‘diocese’ consisting of over 3,000 chaplains serving all around the world. By 1943, there were more than 100 chaplains from the Archdiocese of Chicago in the armed forces.

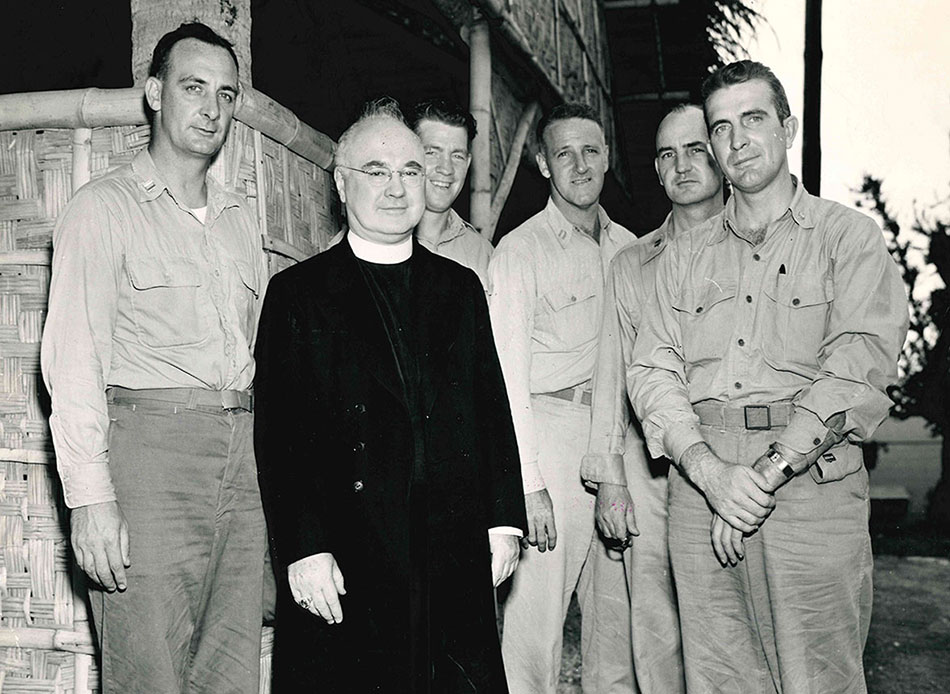

Francis Cardinal Spellman visiting Chicago chaplains in Guam, 1945. Taken from the New World Photograph Collection.

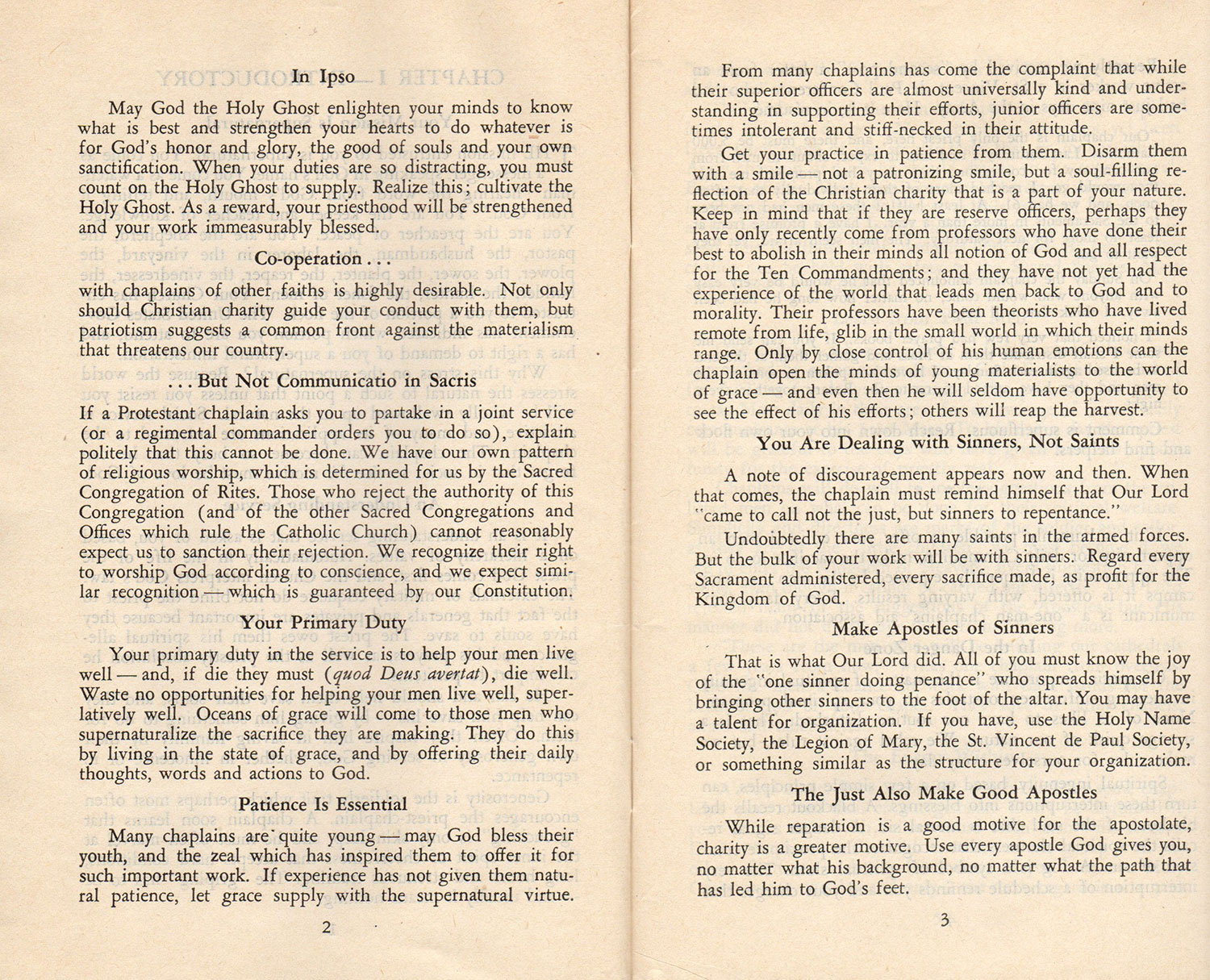

As a Catholic chaplain, Beyenka was expected to be diligent in administering the sacraments to his men. While he could offer spiritual counseling and support to men of other faiths, he was instructed not to participate in interfaith celebrations out of respect and fidelity. Similarly, he was not to offer sacraments to non-Catholics.

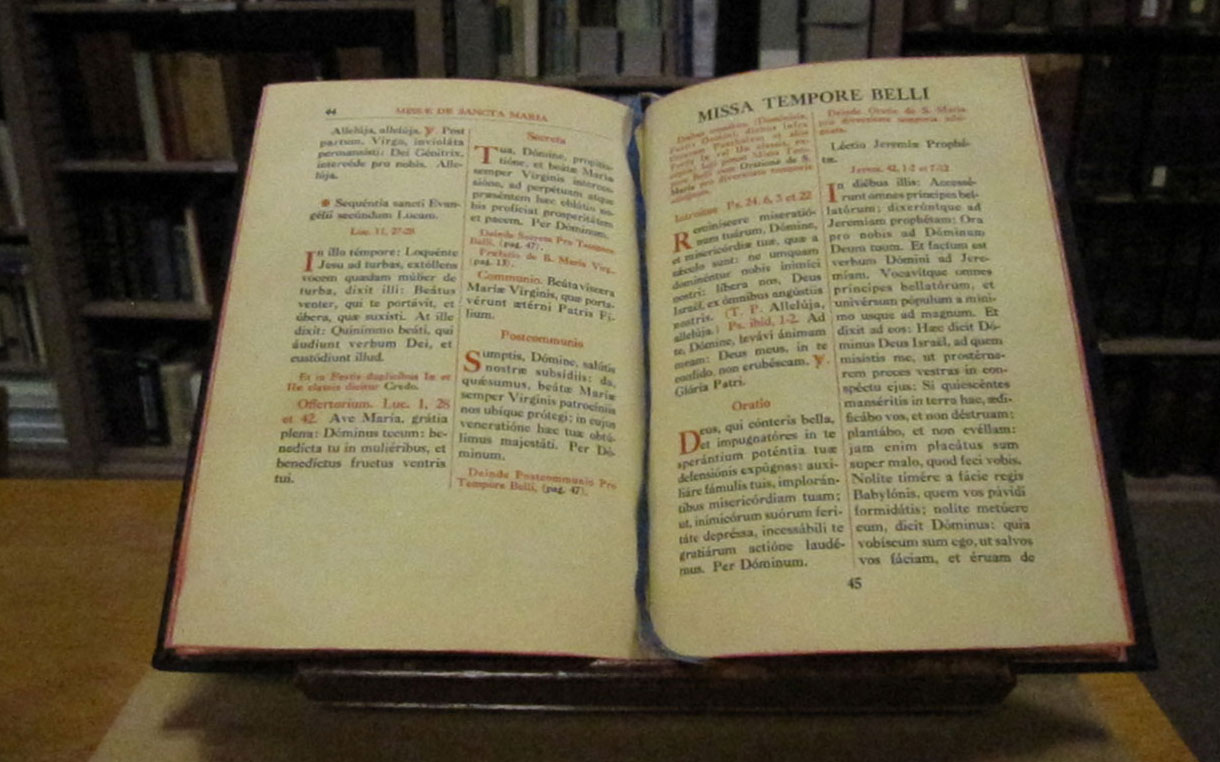

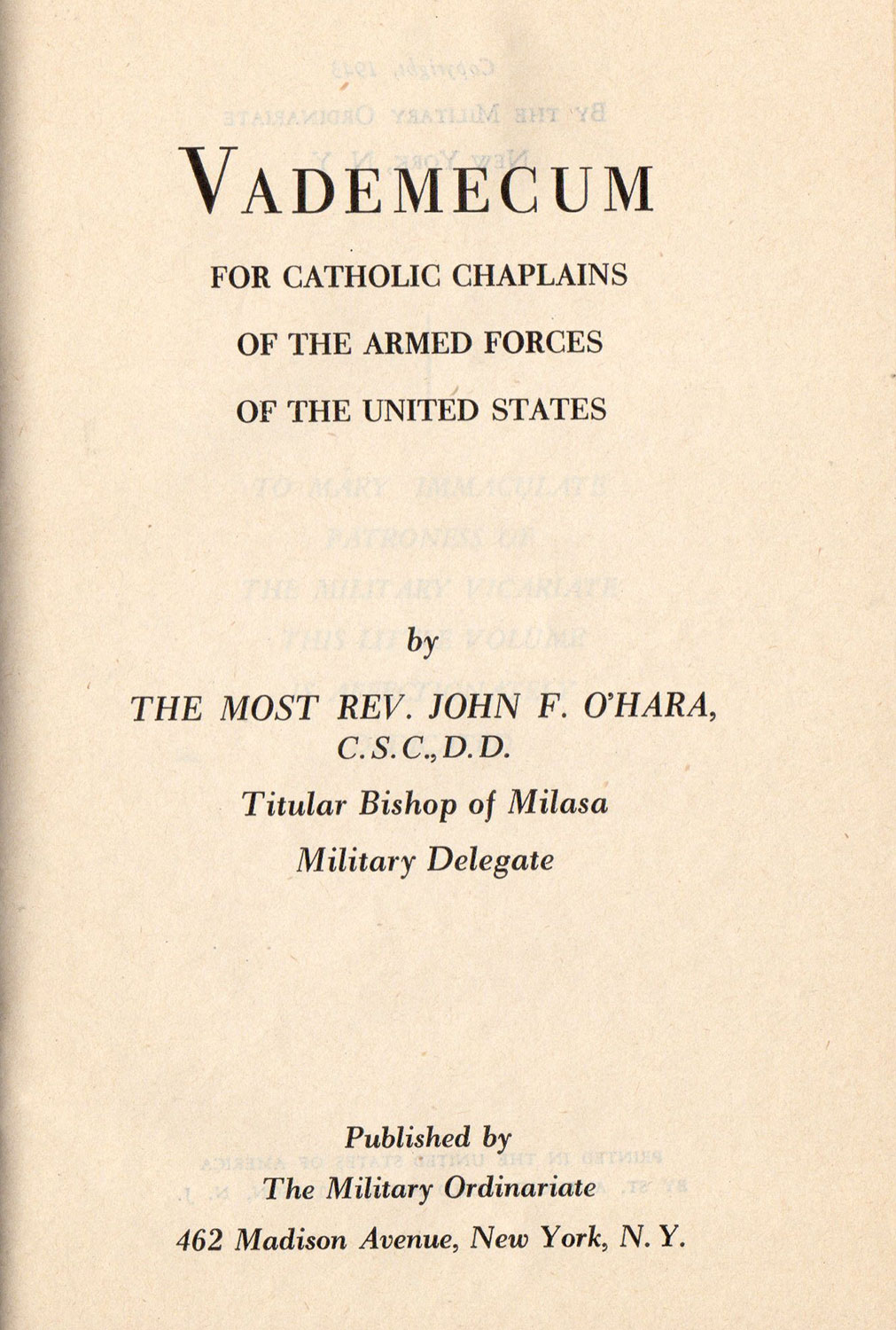

These rules and regulations were set up by the Military Ordinariate to guide chaplains in their Catholic duties. Every chaplain received the Vade Mecum, a manual that offered instructions and advice for spiritual counseling, sacraments, prayer, and all manner of behavior. The Vade Mecum recognized that Fr. Beyenka was not going to be shepherding under ideal circumstances and urged patience and understanding—noting that the priest ought to “make apostles of sinners.”

Fr. Beyenka placed a great deal of emphasis on the mass and communion. Daily mass attendance was often low, but he reasoned that the men of his battalion went to church more now in the army than they ever did at home. Weekly mass drew all the Catholic men together and had to be done out in the field. Chaplains were instructed that the mass could be held anywhere so long as the location was “decent.” John remarked to his parents that he said the mass so frequently he was “surprised how much… I know by heart.”

Beyenka wrote that he frequently gave men communion and confessions before combat, to put the soldiers on good spiritual footing. The Ordinariate estimated that the Eucharist was given one million times per month to soldiers.

“...a wise chaplain will teach his men how to supernaturalize [their] self-control and make it into the coin that buys rewards in heaven”

The Priest Goes to War, 1945

Keeping soldiers on the straight-and-narrow was a difficult and arduous process. The Army had a vested interest in having men exercise “self-control” and leaned on their spiritual advisers to help with the program. Naturally, sex education was an important component of army discipline.

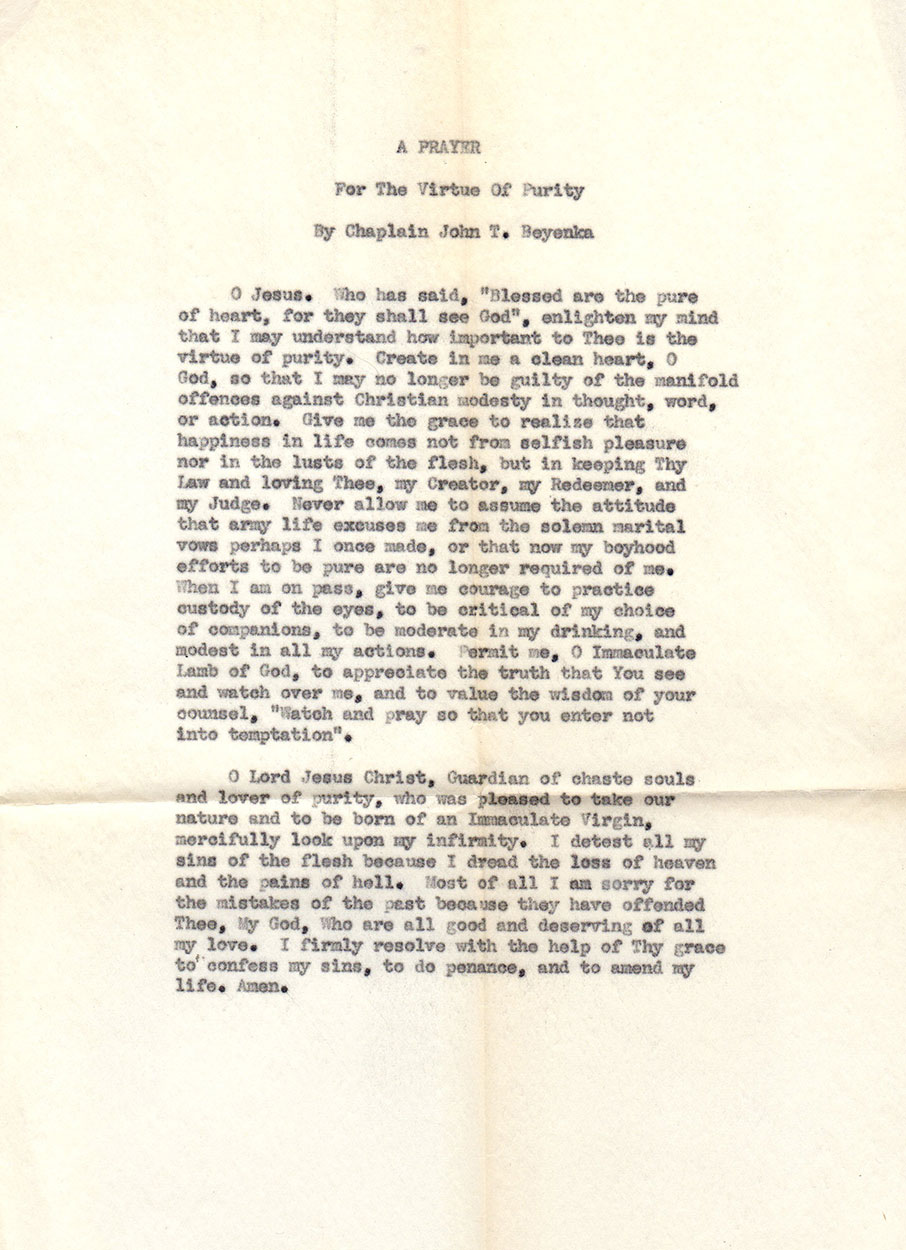

John did his part by offering a weekly “customary sex morality lecture” and distributing prayers to the men, like the one below, to remind them of war’s less-mentioned spiritual minefields.

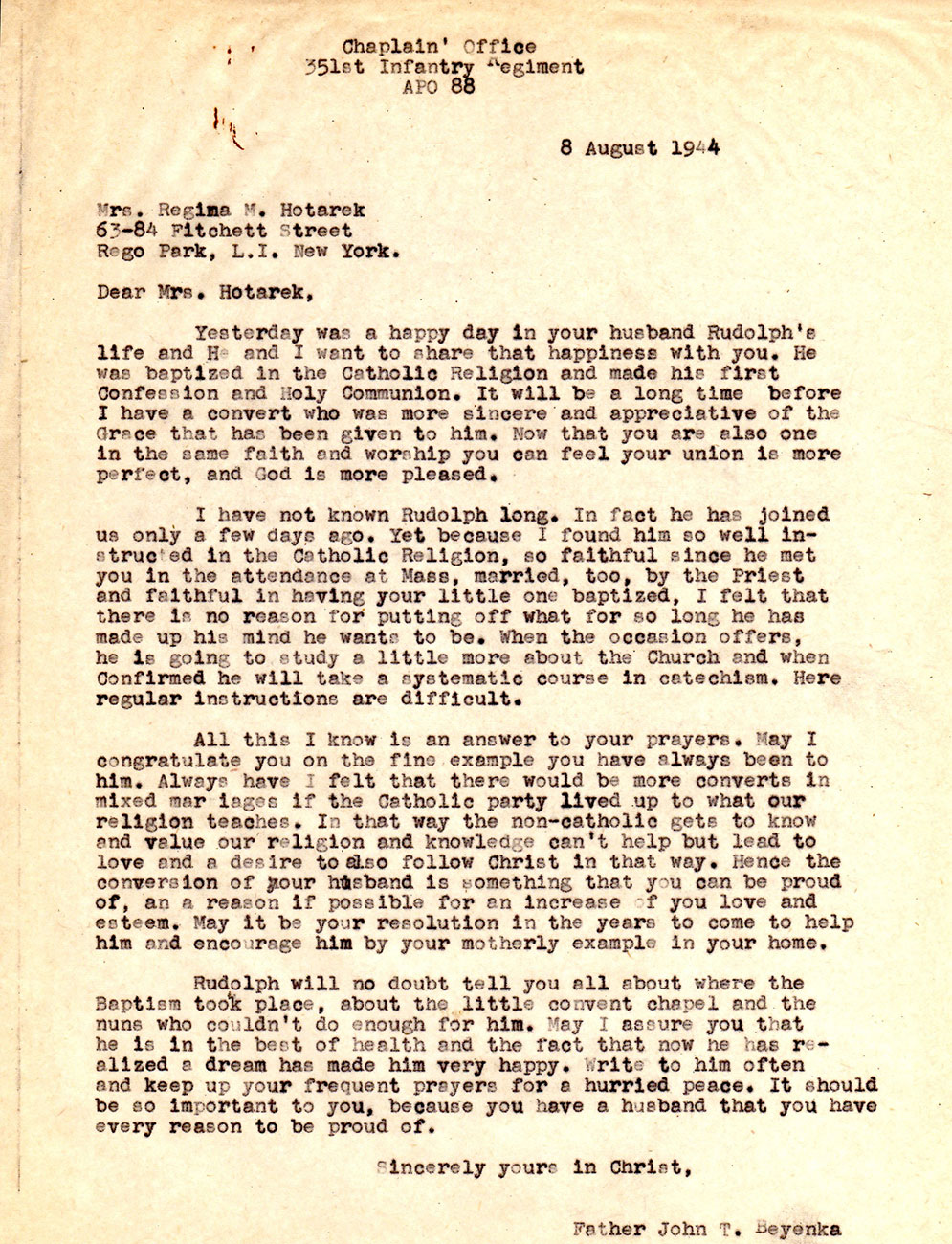

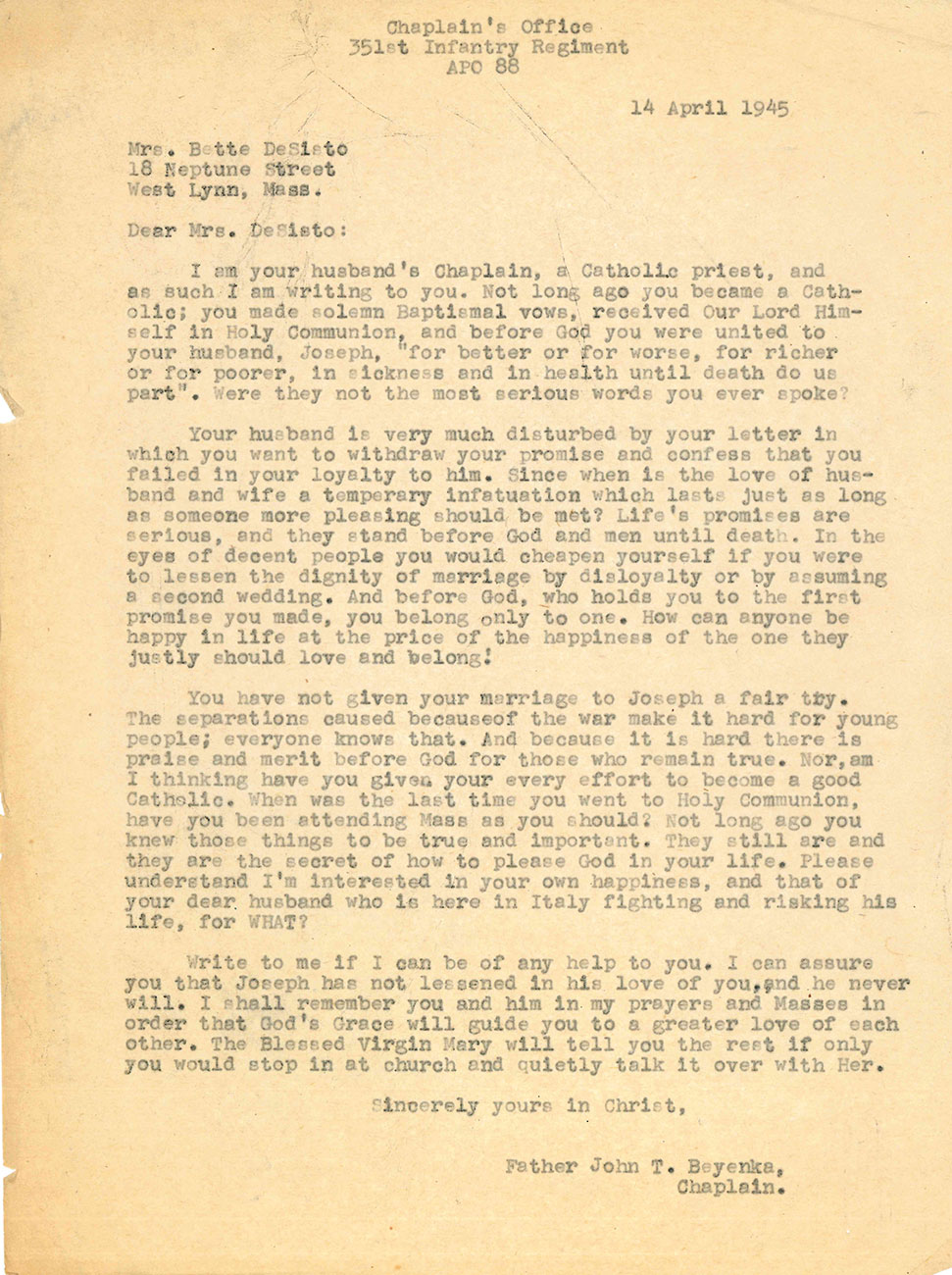

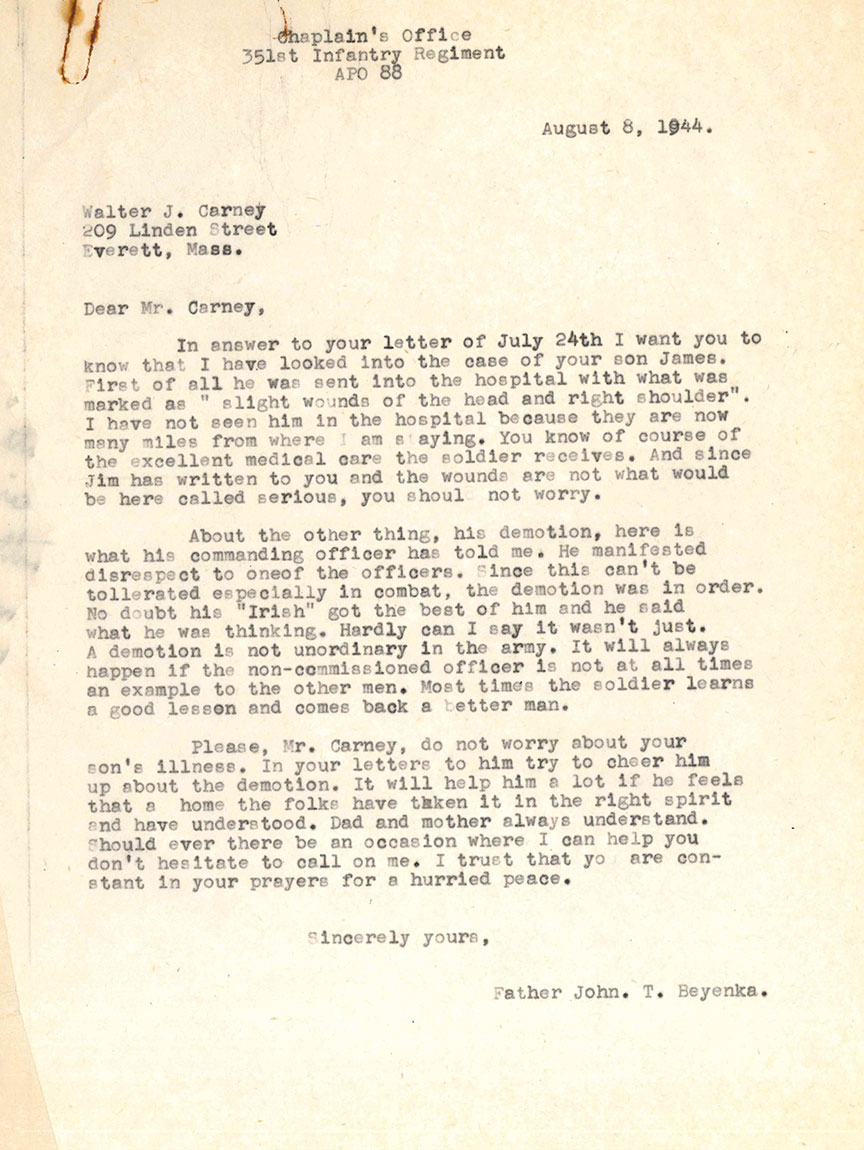

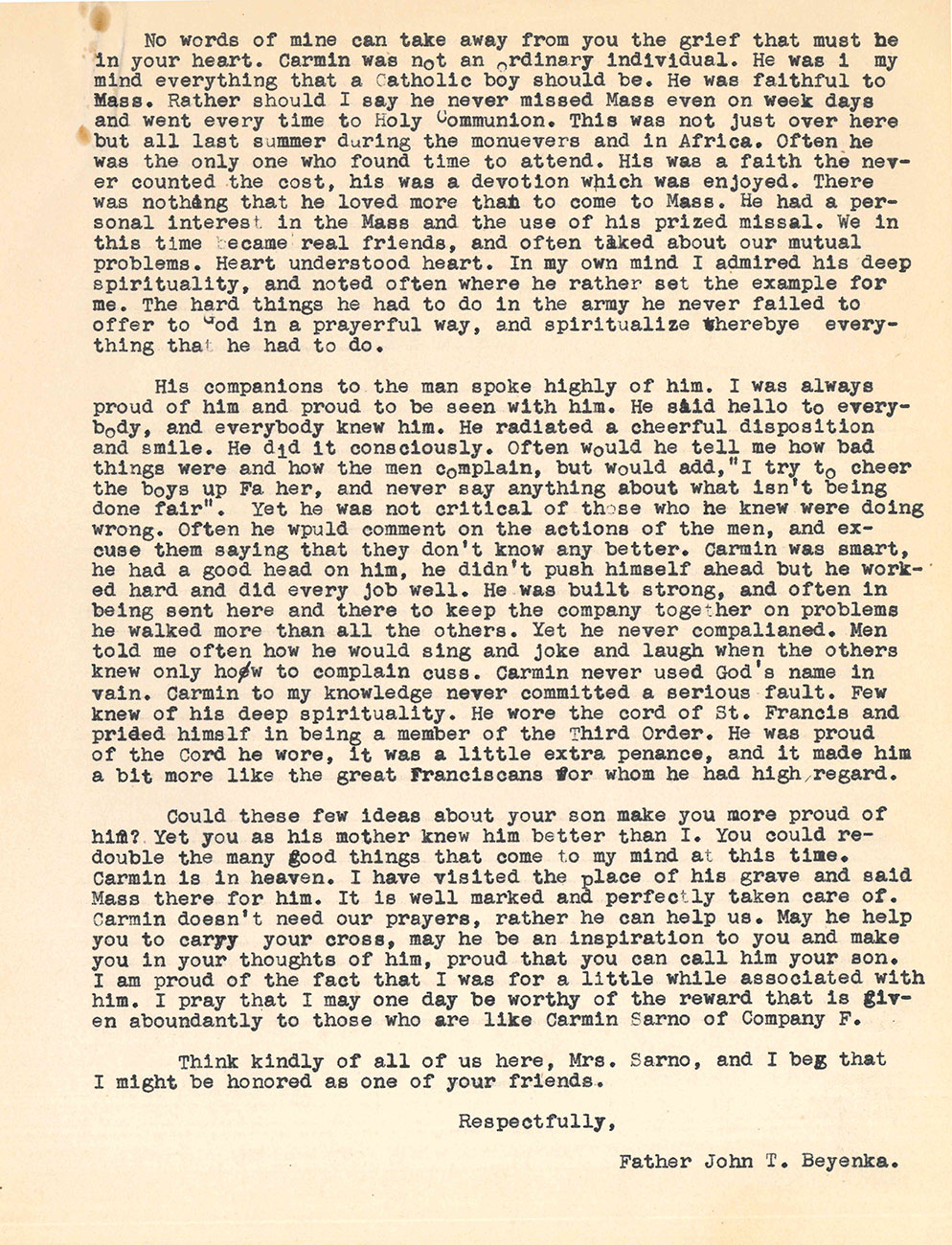

Moral counseling and support did not stop with the soldiers. One of Fr. Beyenka’s most important jobs was to communicate with the wives, mothers, and fathers at home about their sons. These letters covered everything—whether the men had been captured or wounded, why they had not written home in a while, relaying family news. These letters could range from light-hearted to deadly serious. In this selection, you can see Fr. Beyenka’s joy in bringing a convert into the faith, his disquiet over potential marital infidelity, and an amusing consolation to a father who learned of his son’s demotion.

“A Bitter Baptism of Fire”

“I could tell you so much about what I’ve been through. I prefer to forget.”

Fr. John Beyenka, letter to his parents, June 7, 1944

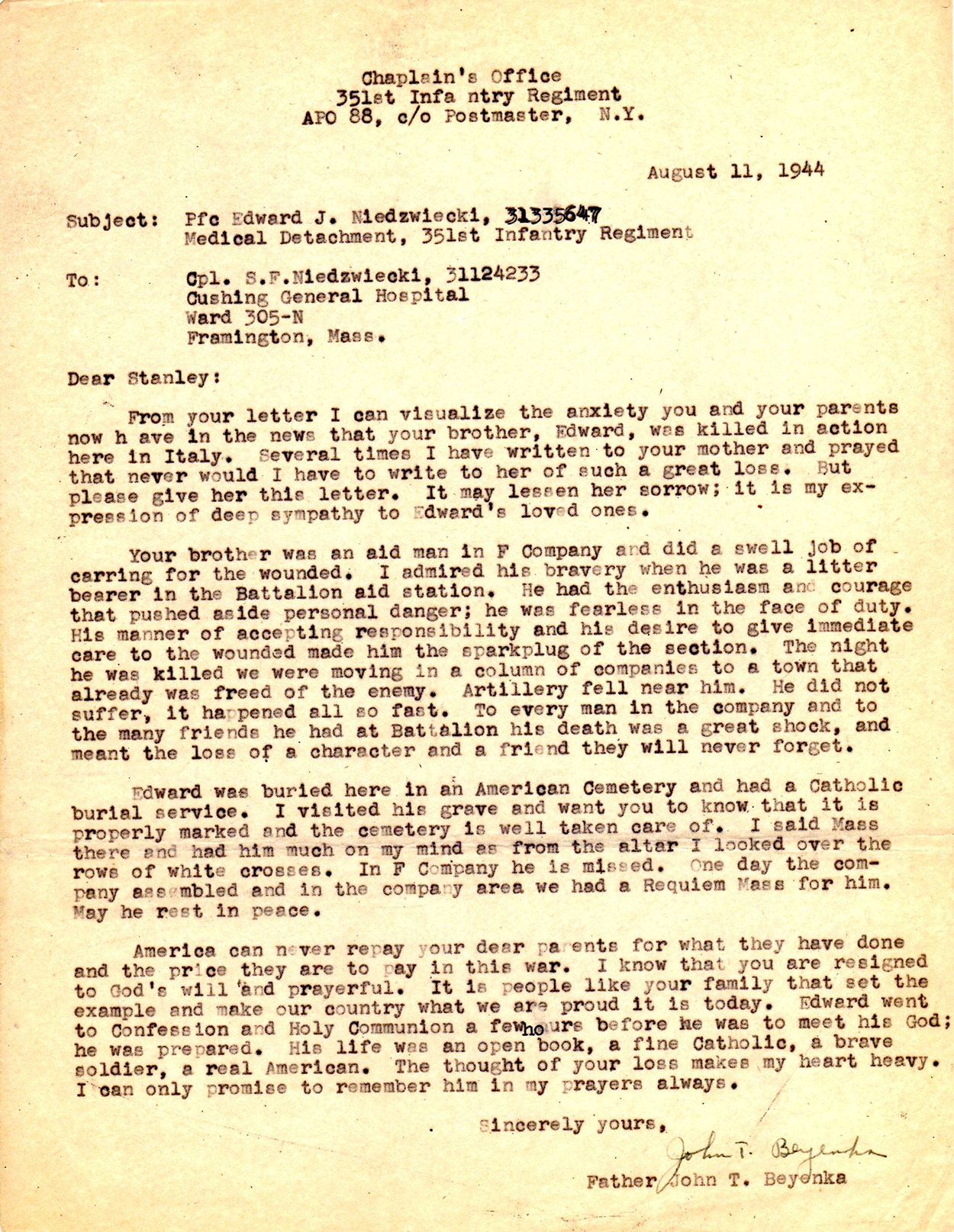

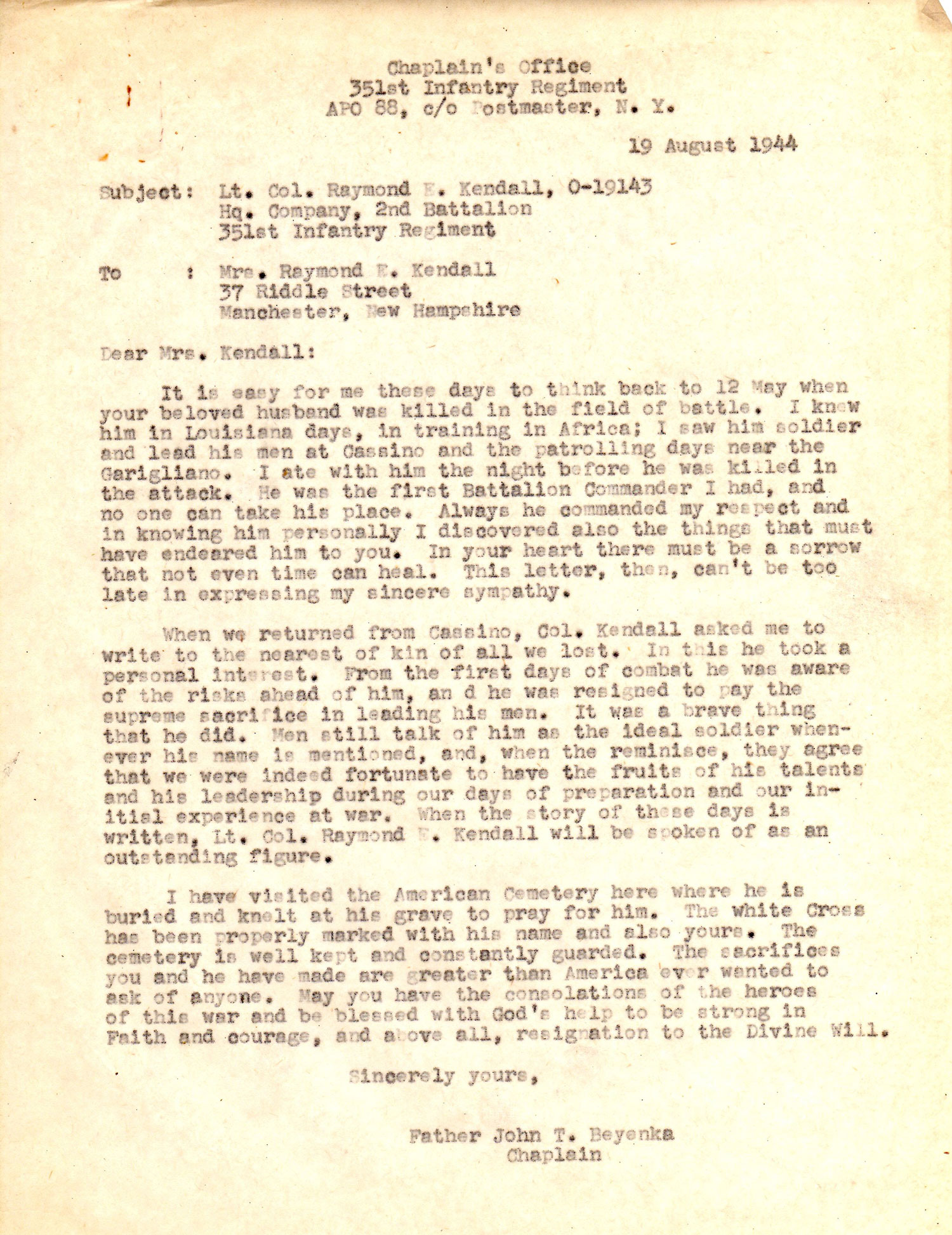

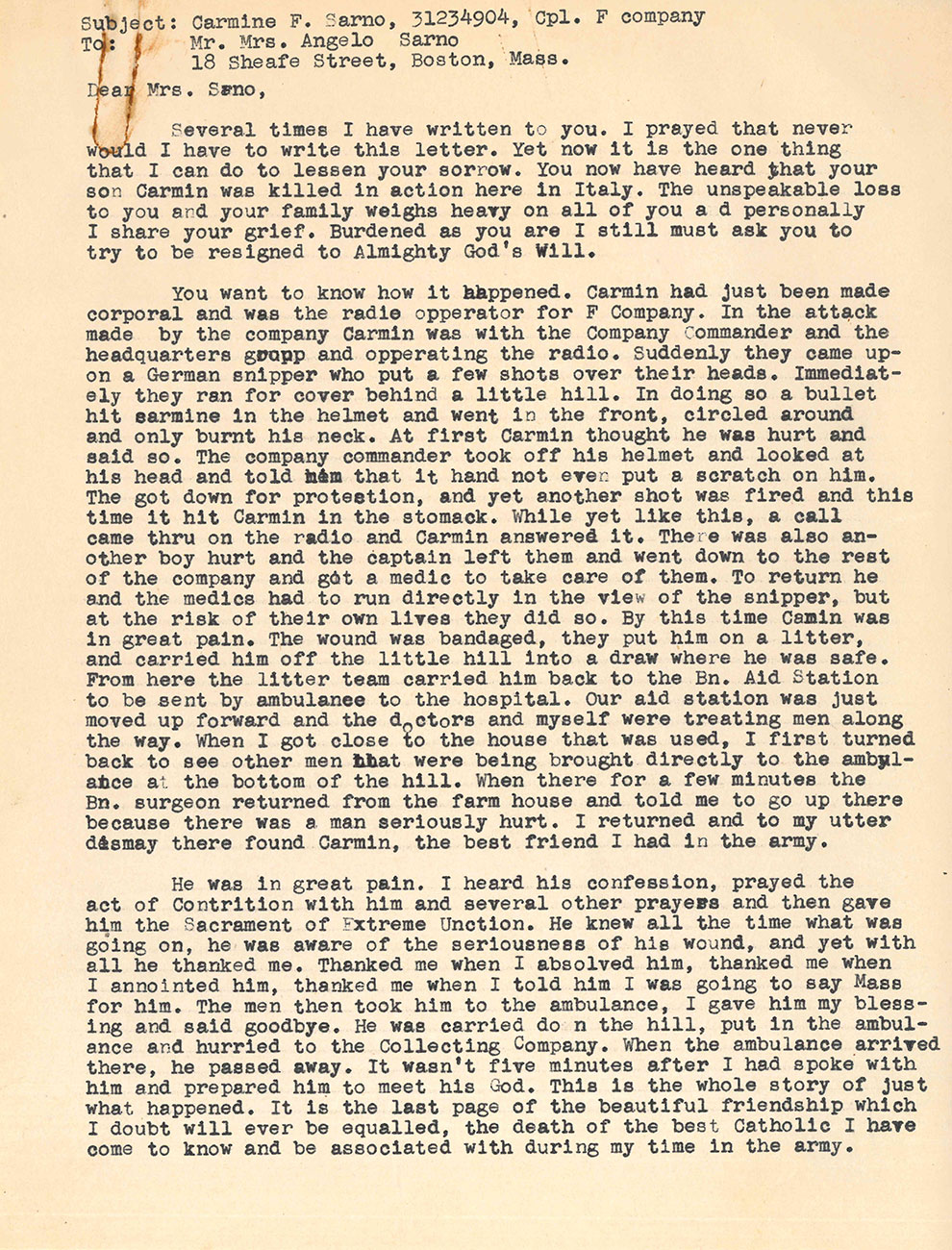

As soon as the 88th arrived in Italy, they encountered nearly constant heavy fighting. Although British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had predicted that Italy would be the “soft underbelly” of the Axis, a grueling campaign through mountainous terrain awaited the Fifth Army and its French Goumier (or Moroccan) allies. Speaking to a reporter, Fr. John called the arrival a “bitter baptism of fire.” Death was ever present and often spontaneous. Fr. Beyenka was with his division on the front lines, helping move casualties into the medical tents and sometimes offering last rites to men in their dying moments. Beyenka noted that religious differences among the men quickly melted away in the heat of battle.

At the battle of Santa Maria Infante, the 5th Army was tasked to break through the fortified Gustav Line. This defensive position stretched for miles and was peppered with mortar batteries and machine gun nests. The Gustav Line was the major Axis bulwark defending northern Italy. In the fighting that followed (May 11-14, 1944), entire companies (each containing 170 men) were wiped out.

One story illustrates the capricious nature of the fighting. Frederick Faust, a 51-year old pulp adventure writer and screenwriter with the pen name Max Brand, had joined the 351st as a wartime correspondent. He wanted to experience a soldier’s life first-hand with the hopes of writing a war novel back home. He volunteered to be with a squad as it made the first attack at the battle around the town of Santa Maria Infante. The signal came for the attack to start. A shell exploded nearby; he died seconds later. Reflecting on Brand, Fr. Beyenka remarked that he was “brave and foolish.”

After several horrific days, the 88th and other divisions broke through the Gustav Line, capturing the town and causing a widespread German retreat further north. The ferocity and aggressiveness of the 88th left an impression on the Germans. In their radio communications and propaganda, they began referring to the Division as the “Blue Devils,” a nickname Fr. John and his fellow soldiers proudly adopted as their own.

“When you get this letter the events of these days will be glorious pages of history. … My life has been marked red with important days… I’ve a great faith in the millions of prayers being said at home.”

Fr. John Beyenka, letter to his parents, May 11, 1944

After Monte Cassino, John’s battalion commander, Lt. Col. Raymond Kendall, charged him with writing letters to the home front informing families of their sons’ deaths. Fr. Beyenka did his best to comfort the grieving families, offering his own reflections and spiritual counsel. Some letters are highly personalized. However, dozens of letters are virtually identical down to the cause of death, with only the name changed. In the hundreds of letters John wrote, one begins to glimpse the awful reality behind them. A selection of them are shown here.

“Never did I trust in Him more. I’m fighting for courage to be what I know I should.”

Fr. John Beyenka, letter to his parents, October 12, 1944

The Blue Devils Enter Rome

After breaking through the Gustav Line, the 351st Regiment pursued the enemy northward through the mountains of Italy, irrupting through a second menacing fortification dubbed the Hitler Line. Fr. Beyenka and Fitz followed in their jeep as the Fifth Army chased its major objective: the capture of the German 10th Army and the fall of Rome as the first Axis capitol. While away from the front lines, Fr. John continued to steel his men for the fight ahead through prayer and the sacraments.

The Fifth Army’s commanding officer, General Mark Clark, forewent the pursuit of the 10th Army and directed the 88th to occupy Rome, which had been largely abandoned by the Nazis outside of a few tank battalions in the surrounding countryside. On June 4, 1944, Fr. Beyenka and the 88th were the first Allied troops to enter the Eternal City, where they were greeted as heroes.

Newspapers at home gleefully recorded the Chicago priest Fr. John’s entrance into Rome. He was oft-quoted as saying “I hope I get to say Mass at St. Peter’s on Sunday!” Writing to his former parishioners at Sacred Heart, Fr. Beyenka said that he had “lived a lifetime since May 11th, and on the 7th of June I had a sufficient reward for all my hardships in the Army.”

The reward was an audience with Pope Pius XII, who greeted the 88th Division as liberators, granting them a special audience and blessing, shown here in a Catholic New World photograph. Fr. Beyenka and the other chaplains were granted a private audience with Pius XII and were able to say mass at the Vatican. Beyenka could scarcely contain himself to his family: “I am now happier than I’ve ever been in my life.”

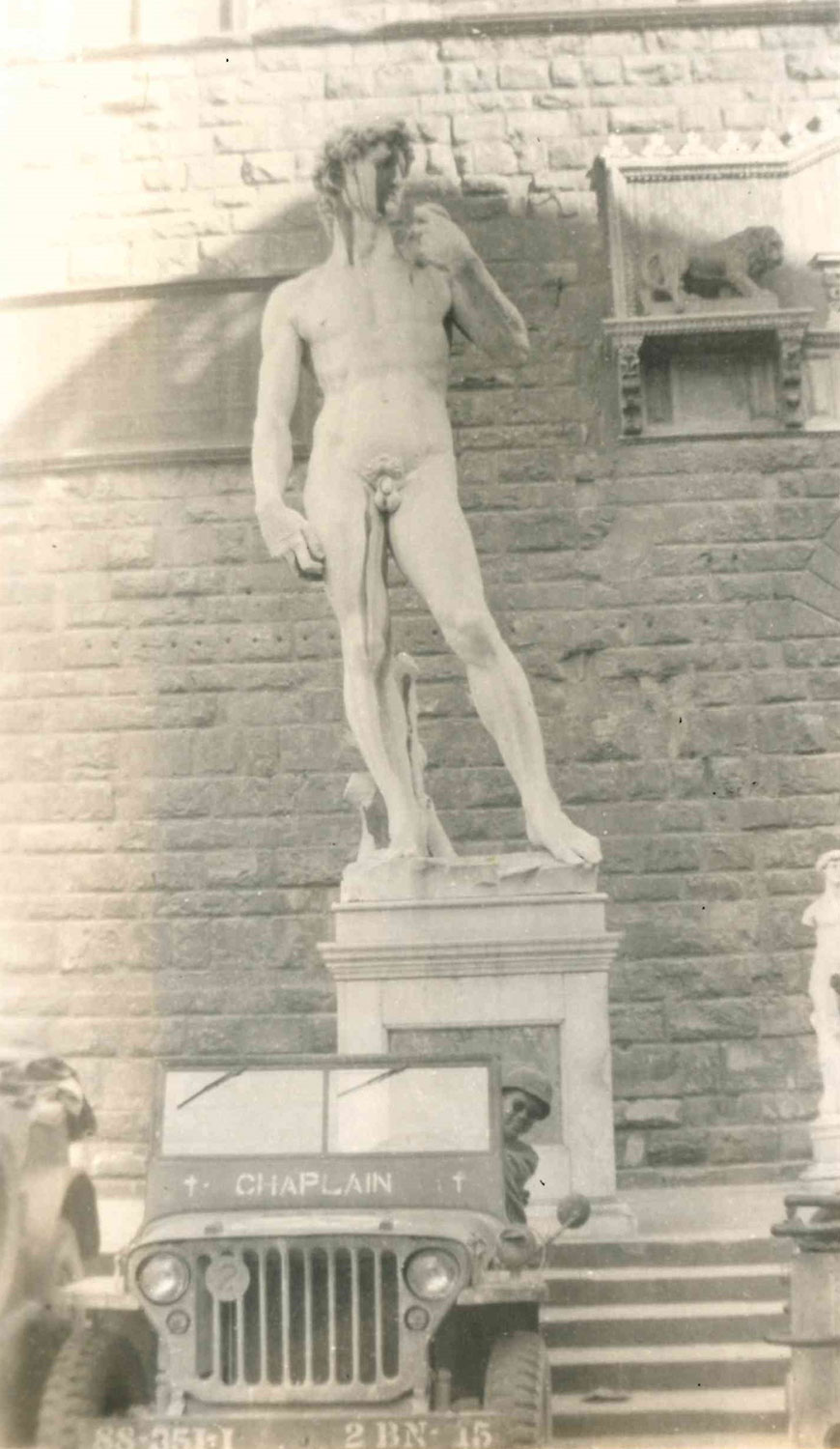

Following the capture of Rome, the Regiment had its first assigned holiday since the beginning of the campaign. The official regimental history notes that Beyenka and the other chaplains “reported unusually high attendance” at their masses. As the city was secured, Fr. John had time to travel the city and fulfill a long-held dream: saying mass at some of the most magnificent churches in Christendom.

With a moment to breathe, there came time to reflect on the past two months. The commanding officers reviewed the combat histories of their battalion and started awarding men for their valor. Beyenka’s scrapbook captures one such ceremony.

Throughout the course of the terrible campaign, Beyenka had been right there with his fellow soldiers, transporting the wounded and comforting the dying. His efforts did not go unnoticed by his comrades and superior officers. On August 3, 1944, Fr. John Beyenka was awarded the Bronze Star for valor in combat.

Despite the respite, Fr. Beyenka was destined to see more fighting before the war’s end. By allowing the 10th Army to escape, Gen. Clark afforded the Germans the time to fortify yet again in the Po Valley as a desperate last defense before the German border. This campaign was a deadly slog, especially as the seasons turned to winter.

With casualties mounting, Fr. Beyenka noticed that there were precious few left from his basic training days in Ft. Sam Houston. Men had died or were wounded, and new recruits had replaced them. Of the original corps of officers that set out to Italy, one was left—a motor officer. Beyenka grimly remarked to his parents “you can imagine what has happened.”

The slow attrition of the front began to bear fruit, no matter how bitterly produced. Cracks in the final defensive lines of the Germans formed in April of 1945, and the 88th Division crossed into the Po Valley. Fr. John Beyenka himself, with a priest liaison on the Axis side, negotiated the surrender of 700 German soldiers, and was given an officer’s pistol. A few days later, all the German army in Italy surrendered.

From Beyenka’s personal notes, he made a final tally:

Killed in Action: 854

Missing or Captured: 613

Wounded in Action: 3159

Conclusion

The end of conflict did not mean the end of Beyenka’s stay in Italy. The Allies wanted occupation forces to stay behind and Fr. John and his remaining compatriots had to relocate into northern Italy and stay put. Sadly, one final tragedy was in store for Fr. Beyenka. His longtime friend, assistant, and compatriot Fitz was killed in a car accident, his jeep driven off the road. John was filled with anguish, telling his parents “I don’t have to tell you how close we were.” Left with almost none of his friends, Fr. Beyenka spent nearly half a year in northern Italy, wondering if he would ever get to go back home.

That day finally arrived. On January 12, 1946, John Beyenka departed on a ship for New York City. Eleven days later, the Chicago Tribune reported that 25,650 troops had arrived home. Fr. John was an army chaplain no longer.

Fr. John’s nephew, Fr. Michael Meany, explains that the Archdiocese wanted returning chaplains to decompress and learn how to live at home again, and gave them easier assignments upon their return. Fr. John was assigned to St. Edmund Parish in Oak Park, considered a quiet, suburban church. Fr. John returned withdrawn, moody, and at times visibly unsettled by his war experiences—what we now know as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). It would take a several years for him to come out of his shell.

What emerged was a man of unique understanding, compassion, and dedication. Fr. Beyenka’s wartime experiences molded his priesthood deeply. He would drop what he was doing to visit parishioners sick in the hospital, and personally reached out to those in grief or sorrow. He further organized an archdiocesan-wide remembrance masses for firefighters killed in the line of duty. By the time he had retired from being the pastor of St. Monica Parish in 1983, he gained the reputation of a caring and compassionate priest, giving freely of himself to those in need.

Bibliography

Researched and Written by Charles Heinrich, CA. Charles received his MA in History from Loyola University Chicago in 2015 and is an Archival Technician at the Joseph Cardinal Bernardin Archives and Records Center. In the summer of 2020, Charles received his CA from the Academy of Certified Archivists.

Special thanks are due to Fr. Michael Meany, nephew of Fr. John Beyenka, for donating his uncle’s materials to the Archives and Records Center, supplying additional historical materials and participating in an oral history interview for the sake of this exhibit. Fr. Meany is currently the pastor of St. John Brebeuf Parish in Niles, Illinois.

History Records - Historical Records - Rev. John T. Beyenka Collection. HIST/H3300/73-76. Joseph Cardinal Bernadin Archives and Records Center, Archdiocese of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

History Records - Photographs - Rev. John T. Beyenka Collection. HIST/P2900/236-240. Joseph Cardinal Bernadin Archives and Records Center, Archdiocese of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

History Records - Ephemera - Rev. John T. Beyenka Collection. HIST/E6100/22. Joseph Cardinal Bernadin Archives and Records Center, Archdiocese of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

“10,000 Yanks in Rome Hear Chicago Priest,” Catholic New World, June 16, 1944.

“Battlefield Vow Fulfilled as Ex-Army Chaplain Visits Family of N. End Hero.” (publication unknown)

Beyenka, Barbara, OP. “A Tree Takes Time.” http://vinnie.pbworks.com/f/A%20Tree%20Takes%20Time%20in%20PDF.pdf (Accessed May 2020).

Catholic New World, September 8, 1944.

Champeny, Arthur S. History of the 351st Infantry Regiment, 88th Infantry Division. Kensington, Maryland: 88th Infantry Division Association, Inc., 1976.

De Luce, Daniel. “Food Scarce in Rome; Water System Wrecked,” Atlantic City Press, June 5, 1944.

Kent, Carleton. “Chicago Priest Prays for Son of Allah,” Chicago Times, April 25, 1944.

“Got His Wish,” Chicago Daily News, June 1944.

Madlener, Dolores. “5 Mins with Father: His Parents’ Legacy: Faith, Family, Education,” Chicago Catholic, August 30, 2009. http://legacy.chicagocatholic.com/cnwonline/2009/0830/5min.aspx (Accessed March 2020).

Meany, Michael (Rev.), personal communication, October 26, 2020.

Morgan, Edward. “Don’t Look Now Adolf, but it’s a Huge Convoy,” Chicago Daily News, 1943

Morgan, Edward. “Shows Sustain Yank Morale on Way Over,” Chicago Daily News, 1943

O’Hara, John F. (Most Rev.). Vade Mecum For Catholic Chaplains of the Armed Forces of the United States. New York: Military Ordinariate, 1943.

The Priest Goes to War. New York: Society for the Propagation of the Faith, 1945.

“Rev. John T. Beyenka, Catholic Pastor Emeritus,” Chicago Tribune, January 25, 1998. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1998-01-25-9801250066-story.html (Accessed February 2020).

Sacred Heart News, Vol. 7, no. 26. June 25, 1944.

Stokes, John B. (Rev.), ed. “Holy Name News,” Our Lady of Mercy. June 1944.

Vobiscum, Vol. 1, no. 10. October 1945.